Exploring Northern Italy: Team Training Trip

Our Team in Venice.

On 6–12 May, the entire Refashioning team took part of a training trip in Northern Italy. The aim of this trip was to deepen our understanding of the production and use of textiles in Italy during the Medieval and Early Modern period, and to do so, we had decided to move across Tuscany, Emilia and Veneto, the main centres of Italian textile production.

Our week consisted of several formative activities that supported the aim of the trip. We started the week in Florence, one of the European capitals for the wool production in the Renaissance period. On Monday, we took a weaving course in Fondazione Arte della Seta Lisio, where our teacher, Angela Giordano, thought us different regional weaving techniques from Tuscany, Sardinia, Lombardy and Marche. We were excited to learn about the mechanics of different loom types and about the weaving process, and enjoyed the day of concentrated weaving.

Weaving workshop at Fondazione Lisio.

Hard at work.

On Tuesday, after visiting the Museo del Tessuto in Prato, we travelled to Bologna,where on Wednesday we visited the Museo del Patrimonio Industriale. The museum showcases the long industrial history of Bologna, such as the history of local silk production, which made Bologna one of the main European centres for silk production, specialising in in the manufacturing of veils, already during the medieval period. The museum retains a functioning copy of the Bolognese silk mill, one of the first examples of proto-industrial production, and it was fascinating to study the mill and afterwards see the canals that powered the silk mills.

1:2 scale silk mill model at the Museo del Patrimonio Industriale.

Bologna.

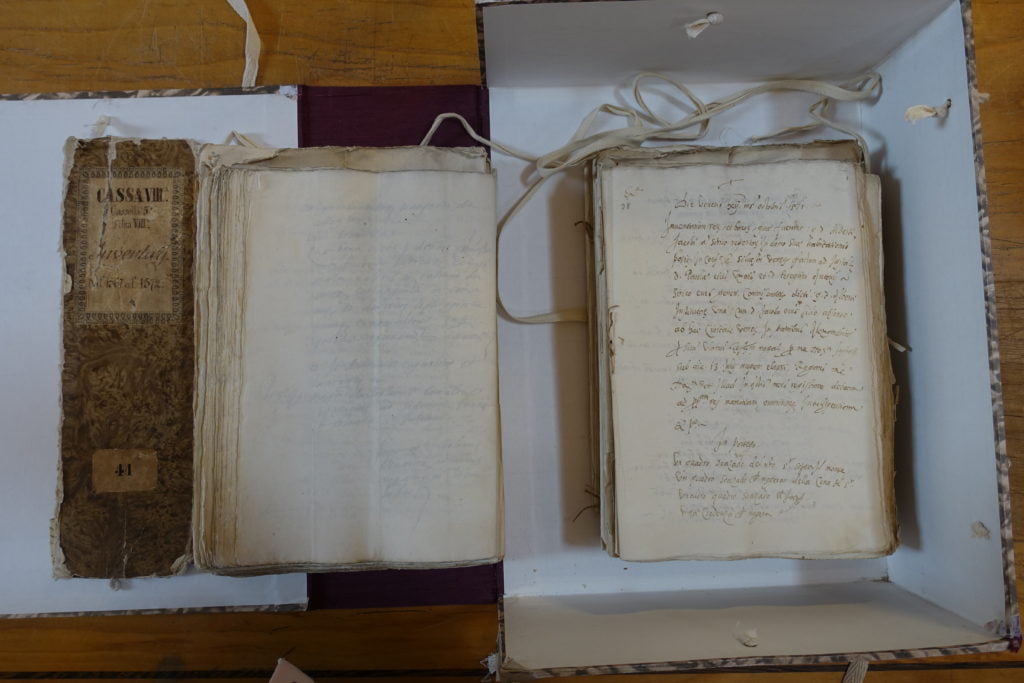

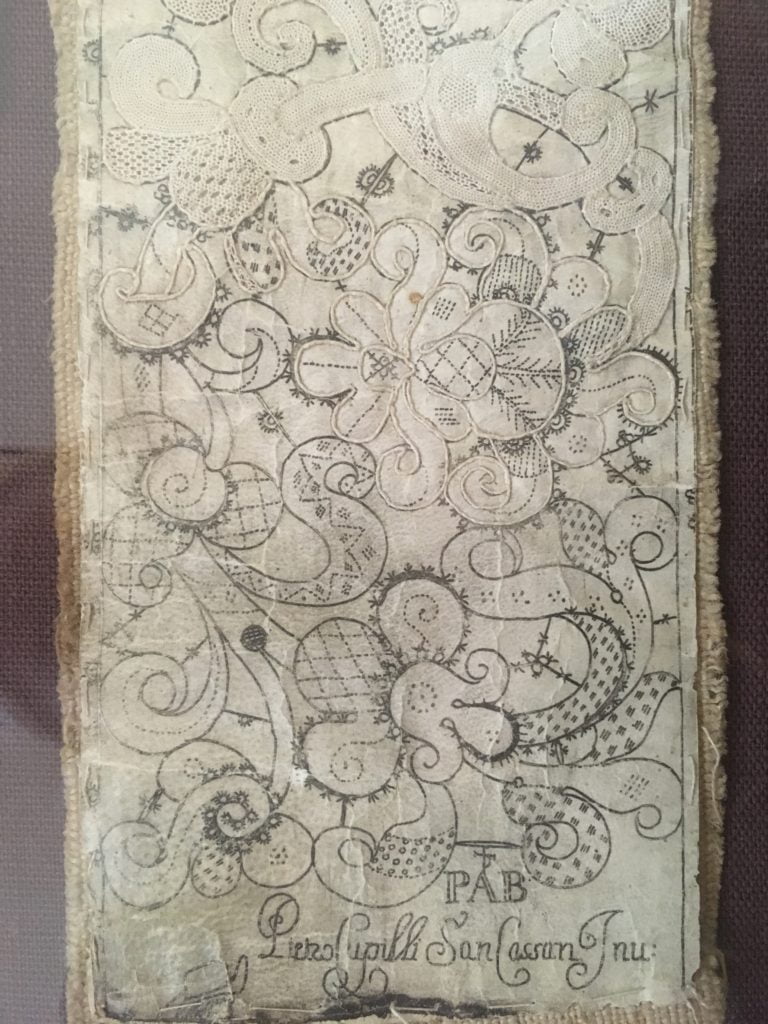

Moving North, Padova was our next stop. On Thursday we had a joint seminar with the Department of Historical and Geographic Sciences and the Ancient World (DISSGeA) of the University of Padua on Fashion and Popular Groups in Renaissance Europe. We met local scholars Andrea Caracausi, Salvatore Ciriacono, Mattia Viale and Francesco Vianello, who talked to us about the production and consumption of silk ribbons, the budget of Venetian artisans and the consumption of textiles of the Veneto women. This opportunity to engage with other researchers and exchange ideas was one of the highlights of our trip, and presented interesting possibilities for possible future co-operation.

Professor Andrea Caracausi giving a presentation on ribbons.

Our team with local scholars in Padova.

To properly conclude our visit, of course, we stayed for two days in La Serenissima: Venice. On Friday, we visited Tessitura Luigi Bevilacqua, one of the oldest – and still active – weaving factories of the city. We had the possibility to see weavers and looms (once used by the Silk Guild of the Republic of Venice) at work,producing the refined soprarizzo velvet, and to touch with our own hands fabrics made following ancient techniques. One of the most striking feature of the workshop was that many of the looms and tools were old, some even from the 17th century, and this gave us some kind of idea what a 17th century weaving workshop might have looked and sounded like.

At Tessitura Luigi Bevilacqua.

At Tessitura Luigi Bevilacqua.

Velvet in the making.

Pattern samples at Tessitura Luigi Bevilacqua.

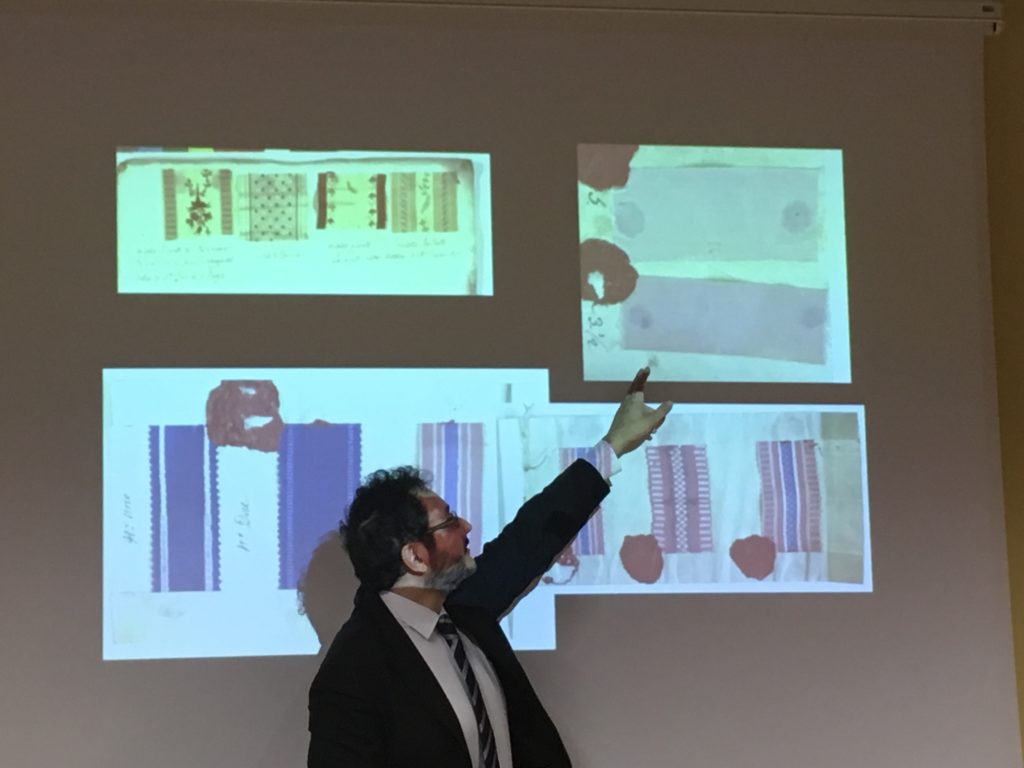

Besides silk, we learnt a lot also about lace. We started our “lace journey” in Burano, at Museo del Merletto, where the production of lace concentrated in the 19th century, and concluded it at Palazzo Mocenigo, with a backstage visit to the museum collections. There our expert guide, Paola, showed us extant examples of Venetian lace from 16th to 20th century, and explained us in detail the history and the manufacturing process. As an extra treat, we got to study and actually hold a 15th century pianelle platform shoe, which had just returned from exhibition in Canada.

Unfinished piece of Venetian lace with it’s original pattern at Museo del Merletto.

Paola showings us details of a 16th century Venetian lace.

Paula was over the moon to hold this 15th century platform shoe in her hands.

In addition to this stimulating programme, we thoroughly enjoyed spending quality time with our team. And of course, our learning efforts were eased by Italian food, culture and lovely weather. After the week we reflected on everything we had learned, and got many ideas for our future events.