Inventories

Inventories are detailed lists of personal belongings, drawn up usually when the head of the household passed away. These post-mortem inventories usually recorded, room by room, all the material goods that were present in the household and the workshop at the time of the householder’s death, including those of the entire family, giving us the possibility to understand how consumption evolved within a range of social classes.

Post-mortem inventories were drawn up for the purpose of establishing the total value of the deceased’s possessions, so that creditors and heirs could settle eventual disputes with more ease. Inventories were the main tool to estimate an inheritance and when a person died, no matter how rich he was, the heirs or their guardians requested a list of all items that could be inherited, as well as to evaluate them. This process could involve several people, from the notary who registered the documents (testaments and inventories) to the person charged to estimate the value (usually a haberdasher, second-hand dealer or an artisan). Alternatively, inventories could be requested by creditors. In such cases, a court was usually involved in the process, and the inventory listed all the objects that were present in a home or, more often, in a workshop, that could be used to refund eventual petitioners.

Inventories could also be written to certify a dowry. When young women married, their fathers provided them with a dowry. This was paid to the groom either in cash, or in the form of objects or estate properties (an amount that scholars more recently started to identify as an anticipation of the inheritance), or in combination of all three. Even though the dowry was usually managed by the groom’s family, women had the right to get their dowries back in the event of the husband’s death. In order to refund the dowry (that she could finally start managing herself), the court usually requested an inventory that specified the suitable objects that were returned to her.

Inventories, and in particular the post-mortem inventories, are an indispensable source for our project, since these documents list – among other possessions- all the garments, accessories and ornaments that the family owned at the time of the householders death. What makes these particularly valuable sources for dress and material culture historians is the fact that the items were often described in a detailed way. Clothing and beauty items are usually listed and described (with colours, length, finishing, trimmings, etc.), giving us the possibility to examine what kind of items ordinary families at artisanal levels wore and how rich their wardrobe was.

However, since inventories are verbal descriptions, often using a personal vocabulary, it is usually quite difficult to identify garments and textiles with precision, especially when it comes to the finishing, cut, decoration and style that characterised an item. This highlights the importance of combining the information with other types of sources, such as other archival evidence, visual sources and printed books – all of which are at the core of the “Refashioning the Renaissance” project research.

Suggested reading:

Berg, M. (1996), “Women’s Consumption and the Industrial Classes of Eighteenth-Century England”, Journal of Social History,30(2), 415-434

Glennie, PD. (1995), Consumption in Historical Studies. In D. Miller (Ed.), Acknowledging Consumption: A Review of New Studies, 164 – 203

Riello, Giorgio. ‘Things Seen and Unseen: The Material Culture of Early Modern Inventories and Their Representation of Domestic Interior’. In Early Modern Things : Objects and Their Histories, 1500-1800, Paula Findlen. Basingstoke: Routledge, 2013

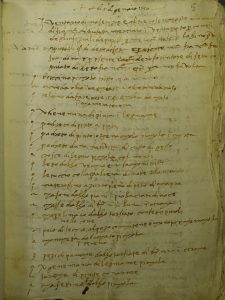

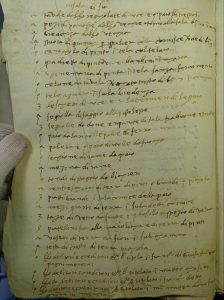

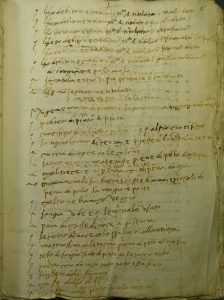

Pictures: Inventory of Francesco di Giosafa, merciaio (5 January 1551).