Sumptuary laws

Sumptuary laws were issued in early modern Europe and beyond, in order to regulate dress and appearance. Although sumptuary laws were designed to limit spending and excess clothing at all social levels, including high-ranking elites, legislation was often particularly strict when it came to luxury clothing at the lower social levels. It was common that, due to their low social and economic status, individuals and families at artisanal levels were forbidden to wear most expensive and prestigious garments made from silk fabrics, such as crimson red or purple silks and velvets, as well accessories that were admired by the elites, including scented gloves, feathers in hats, and slippers. Since sumptuary law documents were often extremely detailed, the source provides an indispensable historical record of the types of garments, textiles and accessories that were used, worn, circulated and desired by men and women, as well as of how these garments were made, decorated, and accessorised.

Sumptuary laws were issued in early modern Europe and beyond, in order to regulate dress and appearance. Although sumptuary laws were designed to limit spending and excess clothing at all social levels, including high-ranking elites, legislation was often particularly strict when it came to luxury clothing at the lower social levels. It was common that, due to their low social and economic status, individuals and families at artisanal levels were forbidden to wear most expensive and prestigious garments made from silk fabrics, such as crimson red or purple silks and velvets, as well accessories that were admired by the elites, including scented gloves, feathers in hats, and slippers. Since sumptuary law documents were often extremely detailed, the source provides an indispensable historical record of the types of garments, textiles and accessories that were used, worn, circulated and desired by men and women, as well as of how these garments were made, decorated, and accessorised.

Sumptuary law documentation consists of several different types of sources.

Statutes: Sumptuary laws statutes, drawn up by city officials that were appointed specifically to control dress, defined the types, quality and quantity of items that each social group was allowed to wear, from silk gowns and velvet trims to hats, gloves and strings of pearl. Such statutes were issued at frequent intervals in all the Italian and Danish towns that we are focusing on in our project. In Florence, for example, new reforms of dress regulations were introduced 14 times during our period of research, 1550-1650, and in Siena 8 times. What makes these a fascinating source for us is that the statutes include a wide range of garments, accessories, jewellery and trims that were in circulation at the time.

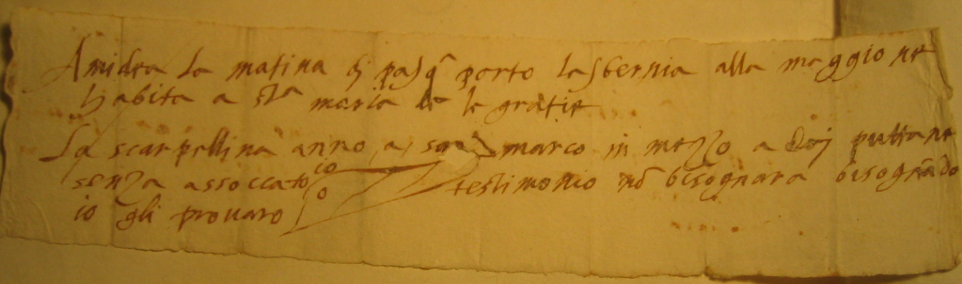

Clothing marking: Often, when the statutes were reformed and new laws were published, the legislators required each individuals to bring each newly prohibited garment that had already been made for inspection within thirty days of the publication of the new law. In Siena, a notary recorded the article in a special register of clothing, specifying the name of the owner, the garment, and the colour and quality of the fabric. Once the owner had paid a small fee of 3 quattrini, the dress was marked with a lead seal that was attached at the hemline of the garment as a sign of the licence. This allowed the owner to wear the dress for three more years, or make alterations on the garment. These books of ‘marcatura’ survive in at least Siena and Bologna, and they provide detailed information about some of the finest and most up-to-date dress that was owned by artisanal population.

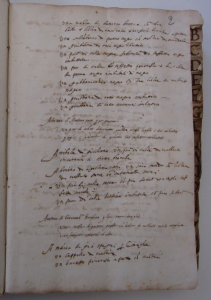

Reports and court cases: In order to enforce the laws, Italian societies established a number of systems to control the laws. The Sienese office of Quattro Censori, for example, tried to control the appearance of the citizens in 1548, by encouraging the city’s inhabitants to report on all offences against sumptuary laws. Anyone above 20 years old could anonymously report of violations, by submitting a secret denunuciation in the wooden box attached next to the palazzo Pubblico. In these notes, the informer declared the name of the offender, the item he or she wore, its quality, how it was against the prohibitions and the time and place where it was worn. Similar system was in Florence, where the state officials caught offenders at taverns, market places, piazze and the entrance of the Duomo, and pinched and ripped off forbidden jewellery and accessories from people’s necks and arms. Some of the reports, or ‘denunzie’, as they were called, as well as the following court prosecutions, survive in Siena and Florence, and they are a great source to study social and cultural attitudes to dress.

Suggested reading:

Bistort, G., Il Magistrato alle Pompe nella Repubblica di Venezia. Studio storico, Reale Deputazione Veneta di Storia Patria 1912 (Bologna 1969).

Bonelli Gandolfi, C., ‘La legislazione ssuntuarie negli ultimi centocinqunta anni dell repubblica’,

Studi Senesi, 34, 1918, p. (Biblioteca: Facolta di legge).

Bonelli Gandolfi, C., ‘Leggi suntuarie senesi dei secoli XV e4 XVI’, La diana, II, 1927, 287-91.

Cantini, L., Legislazione Toscana (Florence, 1805)

Ceppari, M.A & Turrini, P., Il Mulino delle vanità. Lusso e cerimonie nella Siena Medievale (Siena,

1993).

Muzzarelli, M.G., ‘Reconciling the Privilege of a Few with the Common Good: Sumptuary Laws in Medieval and Early Modern Europe’, Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, vol. 39, no. 3, Fall 2009, p. 597-617.

Kovesi-Killerby, C., Sumptuary Law in Italy, 1200-1500(Oxford, New York, 2002)

Lugarini, R., Il ruolo degli “statut delli sforgi’ nel Sistema suntuario senese’, in Bullettino Senese di Storia Patria, 54, 1997, p. 433-422

Image 1: 16th century document recording registered and marked clothing. Archivio di Stato, Siena.

Image 2: Anonymous informant reporting of violations of sumptuary law, 1548, Archivio di Stato, Siena.