Travel Accounts

Early modern Europeans had an increasing interest in the world around them, which was expanding at an alarming rate as travellers reached previously unknown lands and encountered the flora, fauna and people by which they were inhabited. Voyages to the Americas, Asia, Africa and even within Europe were documented in texts and images, or combinations of the two. Costume books, for example, were greatly influenced and inspired by travellers’ accounts and some, such as François Desprez’s Recueil de la diversité des habits (Paris, 1567), suggested these works could take the place of travel for those unable or unwilling to leave home. Similarly, friendship albums, or alba amicorum, commemorated student and others’ journeys with representations of the places and people they encountered as they moved from one university or city to the next.

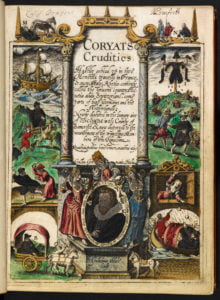

Costume and friendship books relied quite heavily on images, but there were also many accounts that featured only text or just a few images. These kinds of works, such as Luigi Bassani’s I costumi et i modi particolari de la vita de Turchi(Rome, 1545), Thomas Coryat’s Coryats crudities(London: 1611), Hans Staden, Warhafftig historia(Frankfurt am Main, 1557), often describe in great detail lands both near and far, as well as their inhabitants, their customs and – most importantly for our project – their clothing and accessories and gives access to how visitors perceived or understood the style of ‘other’ people´s dress. For example, Thomas Coryat describes the use of ‘fannes’, lovely, elegant and cheap, by all different sorts of people on the Italian peninsula. He also notes that for those with more money to spend, leather umbrellas were available to create ‘shelter against the scorching heate of the Sunne.’

Travellers made numerous remarks on customs, behaviour and people’s appearance also in Scandinavia. The English traveller and physician Andrew Boorde, travelling in Denmark in 1542, for example, noted in his account that the Danish people are very poor, and “ Theyr lodgyng and theyr apparel is very simple& bare”. In 1593, another English traveller commented the local women, stating that, “women as well married as unmarried, Noble and of inferiour condition, weare thinne bands about their neckes, yet not falling, but erected, with the upper bodies of their outward garment of velvet, but with short skirts, and going out of the house, they have the German custome to weare cloakes. They also weare a chaine of Gold like a breast-plate, and girdles of silver, and guilded.”

Although these account must be interpreted with care, keeping in mind the motives and perspectives of the authors, travel accounts nonetheless provide colourful descriptions of everyday life, customs and dress, including rare and ephemeral objects, like paper fans.

Suggested reading:

Peter, Hulme, and Tim Youngs, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing. Cambridge University Press, 2002. (Introduction p. 17-36)

I costumi et i modi particolari de la vita de Turchi. Rome: Antonio Blado, 1545

Thomas Coryat, Croyats crudities. London: William Stanesby, 1611.

Hans Staden, Warhafftig historia. Frankfurt am Main: Weigand Han, 1557.

François Desprez, Recueil de la diversité des habits. Paris: Richard Breton, 1567.

Image 1: Title page from Thomas Coryat’s Coryats crudities (London: William Stanesby, 1611). Image courtesy of the British Library, London.

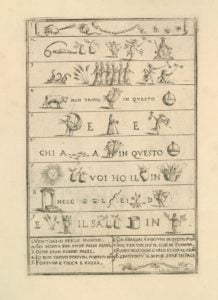

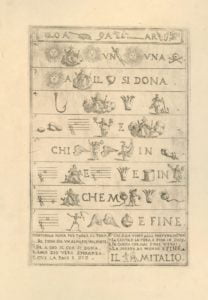

Images 2 & 3: Two side of a rebus designed to be cut out and pasted onto a fan. These kinds of delicate Renaissance objects rarely survive today. Giuseppe Maria Mitelli, Rebus, 1693. Etching, 24.6 x 16.5cm. Images courtesy of the British Museum, London.