Visual Images

Images are a critical source for the Refashioning the Renaissance project, especially those that depict artisans and other lower-class people. Most obvious, perhaps, are paintings such as Vincenzo Campi’s Fruit Seller (c. 1580) (seen on our homepage) or Giovanni Battista Maroni’s portrait of a tailor (c. 1565–70), which present us with a detailed and (literally) colourful view of working people and the clothes they may have worn; however, we must use paintings, and indeed all images, with caution, keeping in mind for whom the works were created and why. Images of dress were often idealized or fantasized by artists in order to convey, for example, religious and moral values, desirable personal qualities, or political ideas

Images are a critical source for the Refashioning the Renaissance project, especially those that depict artisans and other lower-class people. Most obvious, perhaps, are paintings such as Vincenzo Campi’s Fruit Seller (c. 1580) (seen on our homepage) or Giovanni Battista Maroni’s portrait of a tailor (c. 1565–70), which present us with a detailed and (literally) colourful view of working people and the clothes they may have worn; however, we must use paintings, and indeed all images, with caution, keeping in mind for whom the works were created and why. Images of dress were often idealized or fantasized by artists in order to convey, for example, religious and moral values, desirable personal qualities, or political ideas

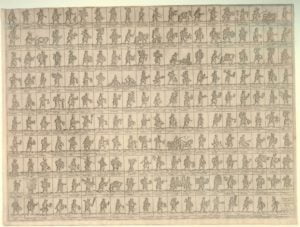

Useful images also come from Renaissance texts, such as those in costume books and alba amicorum, as well as single sheets that were intended for sale on their own or as part of a set. For example, representations of street sellers from various cities became increasingly popular from the sixteenth century, and these representations show a diverse group at work selling their wares, as we can see in Ambrogio Brambilla’s print from the 1580s.

Simon Guillain’s print after Annibale Carracci’s drawing – published in the mid-seventeenth-century but created around the same time as Brambilla’s work above – of a vendor of pictures, show a man selling framed images. Some of these may well have been prints, which were more affordable to working people (though of course were owned by the elite as well). This print also shows us that a person like this might be dressed in a floppy hat, long cloak, loose breeches and soled-hose.

Simon Guillain’s print after Annibale Carracci’s drawing – published in the mid-seventeenth-century but created around the same time as Brambilla’s work above – of a vendor of pictures, show a man selling framed images. Some of these may well have been prints, which were more affordable to working people (though of course were owned by the elite as well). This print also shows us that a person like this might be dressed in a floppy hat, long cloak, loose breeches and soled-hose.

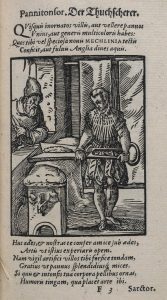

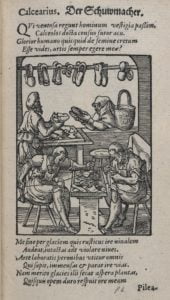

In the sixteenth century, we also begin to see representations of artisans and other at work, both in images and text. For instance, the so-called Book of Trades by Hans Sachs and illustrated by Jost Amman shows more than 100 different trades and professions, including draftsmen and printers – the creators of these kinds of books and images – and those that made or finished textiles and clothing.

Images like these can help us to better understand the working lives of lower-class people, how clothing and textiles were produced, and of course, provide us with an idea of the clothing that men and women wore whilst they were at work. They also invite us to ask questions about their looks. For example, who was the man in the famous sixteenth century portrait of a tailor, painted by Giovanni Moroni around 1570, depicted in a self-confident pose, wearing a fine, pinked cream doublet, red breeches, and a leather belt embellished with a silver buckle, and were his clothes real?

Suggested reading:

Karen F. Beall, Kaufrufe Und Strassenhändler = Cries and Itinerant Trades: Eine Bibliographie..(Hamburg: Hauswedell, 1975).

Marcellus Laroon and Sean Shesgreen, The Criers and Hawkers of London: Engravings and Drawings(Aldershot: Scolar, 1990).

Vincent Milliot and Daniel Roche, Les “Cris de Paris”, Ou, Le Peuple Travesti: Les Représentations Des Petits Métiers Parisiens (XVIe-XVIIIe Siècles)(Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 1995).

Sheila McTighe, “Perfect Deformity, Ideal Beauty, and the ‘Imaginaire’ of Work: The Reception of Annibale Carracci’s ‘Arti Di Bologna’ in 1646,” Oxford Art Journal16, no. 1 (1993): 75–91;

Sean Shesgreen, Images of the Outcast: The Urban Poor in the Cries of London(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002).

Image 1: Giovanni Battista Moroni, The Tailor (‘Il Tagliapanni’), c. 1565-70. Oil on canvas, 99.5 x 77 cm. Image courtesy of The National Gallery, London.

Image 2: Ambrogio Brambilla (engraver) and Lorenzo Vaccario (printer), Ritratto di quelli che vanno per Roma, c. 1580s. Engraving with etching, 42.1 x 51.8 cm sheet. Image courtesy of Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, A171, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Image 3: Simon Guillain after Annibale Carracci, Vende Quadri, 1646. Etching, 27.4 x 16.6 cm. Image courtesy of The British Museum, London.

Image 4: ‘Pannitonsor. Der Thuchscherer. (The Cloth shearer)’, engraved by Jost Amman in Hartmann Schopper, Panoplia omnium illiberalium mechanicarum…(Book of Trades)(Frankfurt: Sigmund Feierabend, 1568). Image courtesy of The British Museum.

Image 5: ‘Calcearius. Der Schuwmacher. (The Shoemaker)’, engraved by Jost Amman in Hartmann Schopper, Panoplia omnium illiberalium mechanicarum…(Book of Trades) (Frankfurt: Sigmund Feierabend, 1568). Image courtesy of The British Museum.