Professional Velvet Weaving

Date: December 2022

Experiment by: Refashioning the Renaissance / Fashion History Lab

Collaborators: Paula Hohti, Elise Piquemal, Kirsi Mantua-Kommonen

How was Renaissance purple velvet professionally made? What did hand woven velvets look like, and what is the state of teh professional craftmanship for velvet hand-weaving today? This experiment tested the use of of historical purple dyes on traditional uncut and cut velvet.

To our knowledge, less than ten weavers mastering specific silk hand-weaving techniques are active in Europe. Passionate and eager to perpetuate their craft, they are facing the difficulty of pushing forward techniques which require expertise, carved from years of training and practice. Yet, the survival of these techniques is essential to sustain the rich specificity of hand-weaving and the diversity of tools.

The weavers’ expertise is also a precious asset for historians, because historical reproductions and studies of fabrics, based on their work, reveal much about the technical structure of historical velvets along with the making process. The ERC-Refashioning project carried out a velvet reconstruction experiment to speculate on the methods and outcomes of what Renaissance silk velvets originally looked like. Together with Elise Piquemal, a professional hand-weaver weaver trained in Manufacture Prelle, the last remaining family-owned silk Manufacture in Lyon, and Kirsi Mantua-kommonen, an expert in contemporary natural dyes and dying, our aims included:

- To integrate rare professional craftsmanship within academic research. Being an expert in their field, the craft person is at the core of the proposals and an effective participant to research.

- To seek which tools can be accessed and mobilised in the context of a research project and historical reproduction, in cooperation with companies.

- To investigate how artisanally dyed silk yarn would be prepared and woven.

- To discuss how combining theoretical and material expertise can enhance the understanding of material culture and promote the available knowledge

The process

The French Mulberry silk yarns were dyed in different shades of purple with natural dyes by Kirsi. We selected the natural dyes based on their availability in Early Modern Europe, and due to them not requiring lengthy processes: Cochineal (Dactylopius coccus), woad (Isatis tinctoria L.), brazilwood (Caesalpina L.), madder (Rubia tinctoria L.), and logwood (Haematoxylum campechianum L.).

The selected dye sources were used in this experiment in the following way: Two of the skeins were dyed with only one dye; cochineal (1) or logwood (6), while the other skeins were dyed in two consecutive dye baths, first either indigo blue with woad and second with shades of red from cochineal (2), brazil wood (3) or madder (4); or, first with logwood and second with madder (5) or cochineal (7), as seen in the resulting range in the picture below. For the full description and analysis of the dyes and processes, including materials applied, the necessary process of mordanting, and the natural dyes, recipes, and dye processes applied, click Purple dye recipes.

1. Cochineal 2. Woad and Cochineal 3. Woad and Brazilwood 4. Woad and Madder 5. Logwood and Madder 6. Logwood 7. Cochineal and Logwood. Photo © Kirsi Mantua-Kommonen.

1. Cochineal 2. Woad and Cochineal 3. Woad and Brazilwood 4. Woad and Madder 5. Logwood and Madder 6. Logwood 7. Cochineal and Logwood. Photo © Kirsi Mantua-Kommonen.

The yarns were then woven by a the professional weaver and our Master’s student Elise Piquemal at Manufacture Prelle. Renaissance velvets were originally woven using a drawloom, but this was not an option for us because the only draw loom accessible in Europe today, placed at La Maison des Canuts, Lyon, was at the time mounted for weaving brocade. As an alternative, we chose to use a Jacquard hand-loom -a traditional silk production hand loom with two mechanic machines, transformed to be used as two smaller sample looms.

During a period of one month, Elise created three velvet samples, using two colours side by side. Each sample demonstrates the use of different rods to create different pile effects. It resulted in a variation of colours reacting with the light in a different manner.

Velvet sample loom – view from the back. Photo © Elise Piquemal, Manufacture Prelle

Velvet sample loom – view from the back. Photo © Elise Piquemal, Manufacture Prelle

Velvet sample loom – the two warps colliding together in the mails. Photo © Elise Piquemal, Manufacture Prelle

Velvet sample loom – the two warps colliding together in the mails. Photo © Elise Piquemal, Manufacture Prelle

Warping wheel and “cantre”. Photo © Elise Piquemal, Manufacture Prelle

Warping wheel and “cantre”. Photo © Elise Piquemal, Manufacture Prelle

Preparation for weaving – “tordage”, twisting the previous warp with the new warp. Photo © Elise Piquemal, Manufacture Prelle

Preparation for weaving – “tordage”, twisting the previous warp with the new warp. Photo © Elise Piquemal, Manufacture Prelle

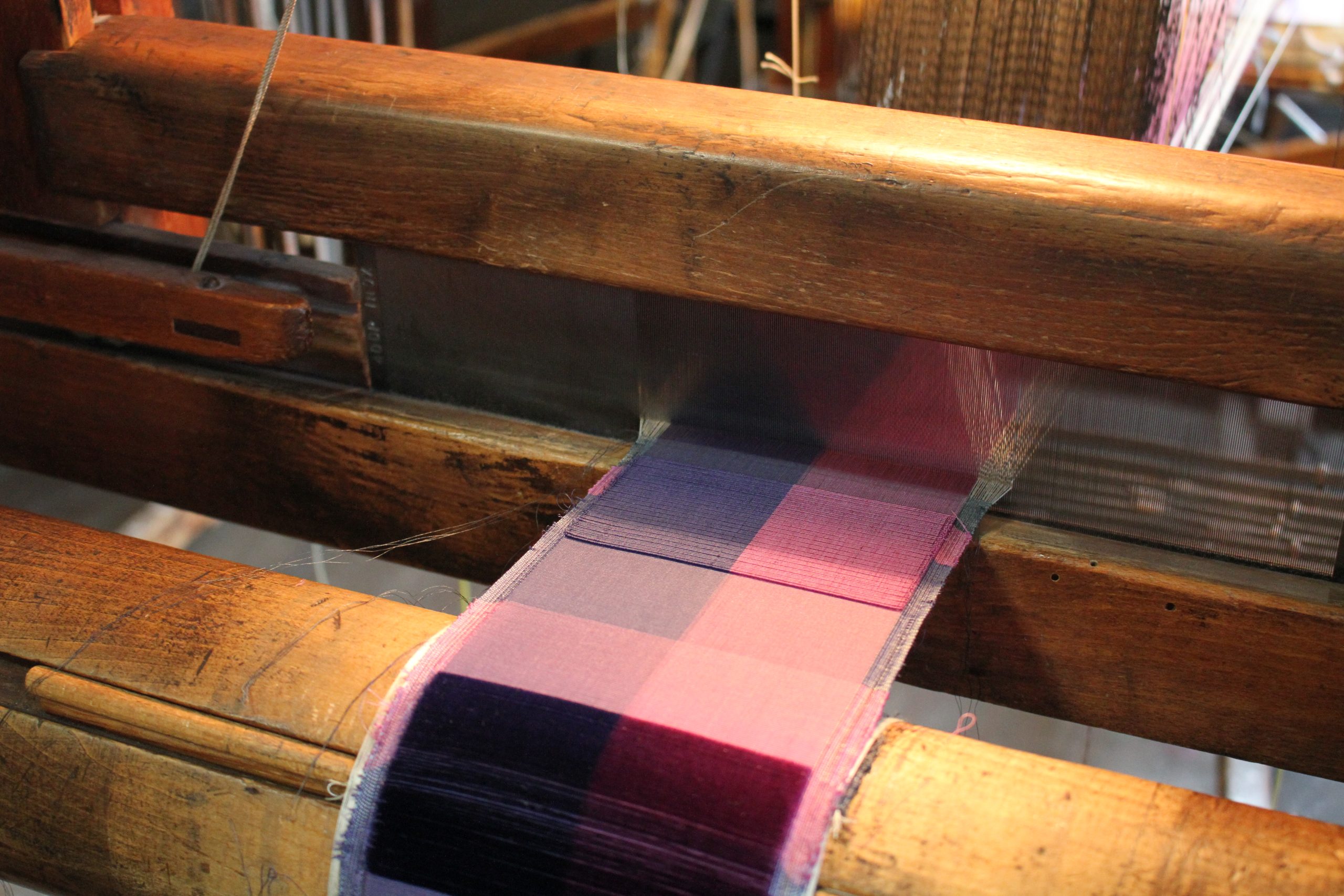

Weaving sample two, woad + cochineal/cochineal. Photo © Elise Piquemal, Manufacture Prelle

Weaving sample two, woad + cochineal/cochineal. Photo © Elise Piquemal, Manufacture Prelle

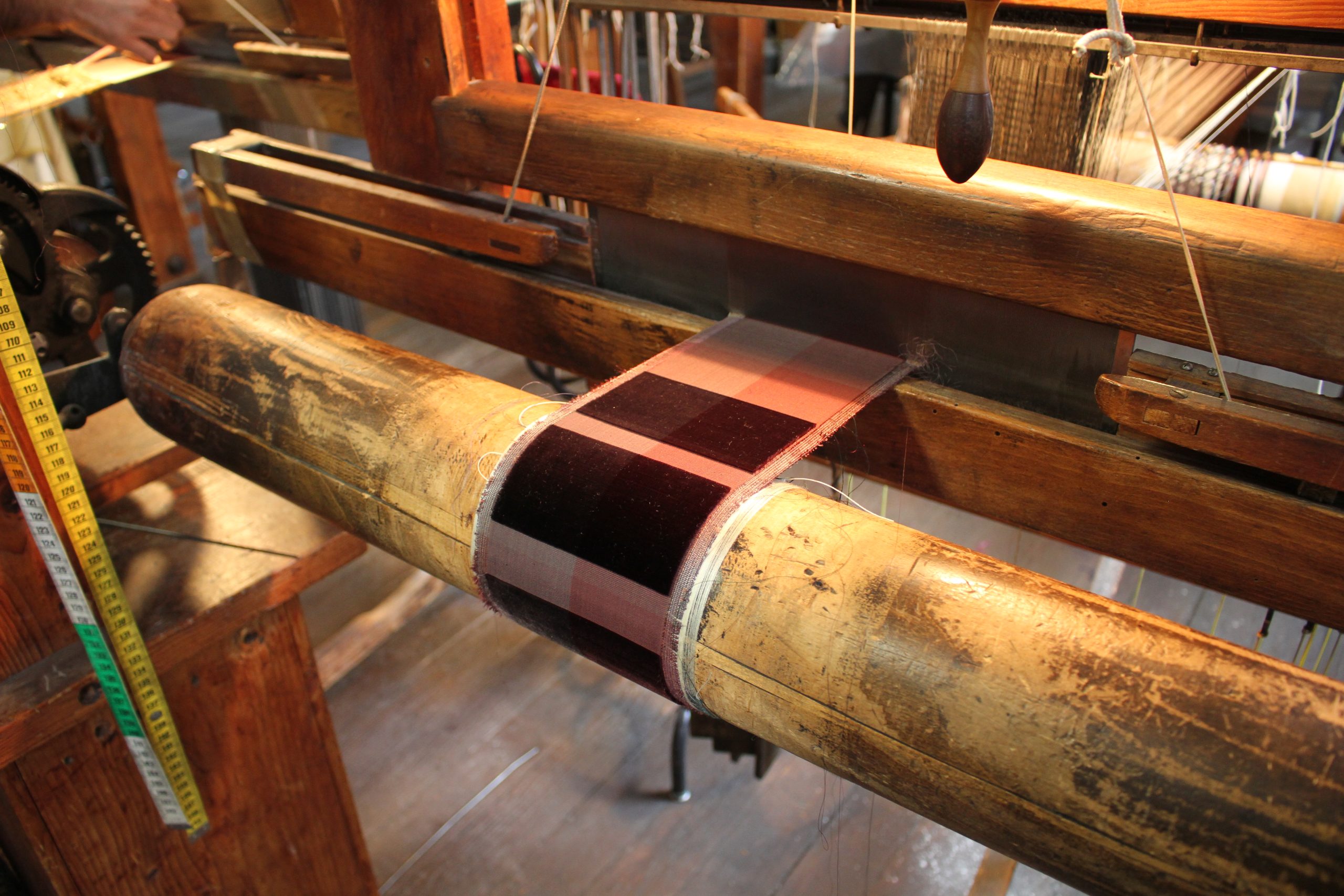

Weaving sample three, madder + logwood/logwood. Photo © Elise Piquemal, Manufacture Prelle

Weaving sample three, madder + logwood/logwood. Photo © Elise Piquemal, Manufacture Prelle

Through this experiment we gained further understanding of the methods and processes of professional hand-weaving. What became immediately clear is the extent to which hand-weaving is time-consuming and weaving velvet requires experience and training. Elise showed us how unforgiving the process is. It is not rare for even a professional weaver to cut part of the warp, and if a mistake happens, the weave cannot be unwoven as the warp is cut. Weaving, futhermore, demands a thorough understanding of the loom, and a clear body awareness. Each stroke and movement difference, ever so slightly, will create a visible mark.

We also achieved several other important outcomes. Among others,

- we collaborated with companies in the silk industry remaining in France, sharing successfully our goals while adapting to their requirements. Our experiment proved that our interests are common and can unite.

- we tested traditional dyeing and weaving methods in our contemporary context.

- we experienced small-scale production and sampling methods, verifying its flexibility and adaptation to research purposes.

- by combining the experience previously built with academic methods, we created the possibility of taking a distance with the “work” aspect, facilitating its analysis through documentation.

- we witnessed how this type of collaboration can open a new area of possibilities, both for the textile research field and the textile makers, to sustain traditional practices and tools.