Man’s doublet, possibly Italian, c. 1550-60. Red satin lined in canvas, trimmed with handmade silk buttons. National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh.

The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh boasts a wonderful collection of clothing and textiles, like the Italian doublet pictured above. This made it the perfect venue for the New Research in Dress History Conference, which took place on Friday the 24th of May. This is an annual event organised by the Association of Dress Historians, and this year it featured seventeen presentations on research spanning the late medieval period to today, and covering North and South America, Europe and Asia.

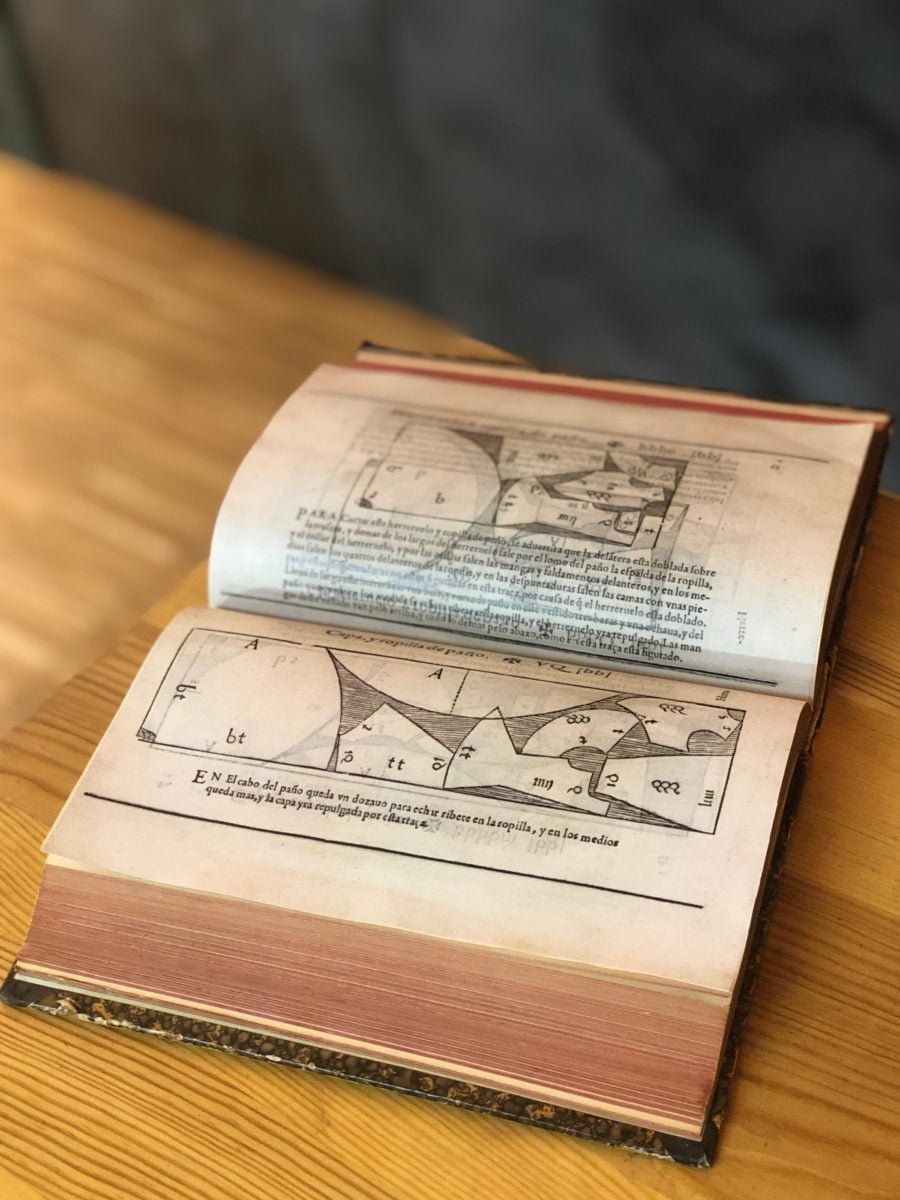

I was fortunate to have the opportunity to present my paper, ‘Books of Secrets and Artisans’ Dress in Italy, 1550–1650′, in the first panel of the day. The paper brought together my research on recipe books and the results of the workshop that the Refashioning the Renaissance project hosted in April. I spoke about the considerable investment that average people living in early modern Italy had to make in order to obtain clothing, drawing on examples from the inventories of artisans’ household that Stefania has been gathering and transcribing over the last 18 months. I then presented some ideas about ways that people might have cared for their clothes – to keep them in good condition and to help them keep their value – based on evidence from recipe books. I then spoke about the project’s ‘Dirty Laundry’ workshop, where we recreated different recipes for stain removers, simple dyes and a perfume for linen chests. As I explained at the conference, recreating the recipes helped us to ask new questions about artisans’ dress, look at things from new perspectives and recognise the importance of socialising and relationships in shaping the ways that people cared for their clothing.

A slide from my presentation showing our team admiring the results of our efforts at the workshop alongside an image of washing day from a German manuscript. Both show the importance of collaboration. Photo copyright Refashioning the Renaissance Project.

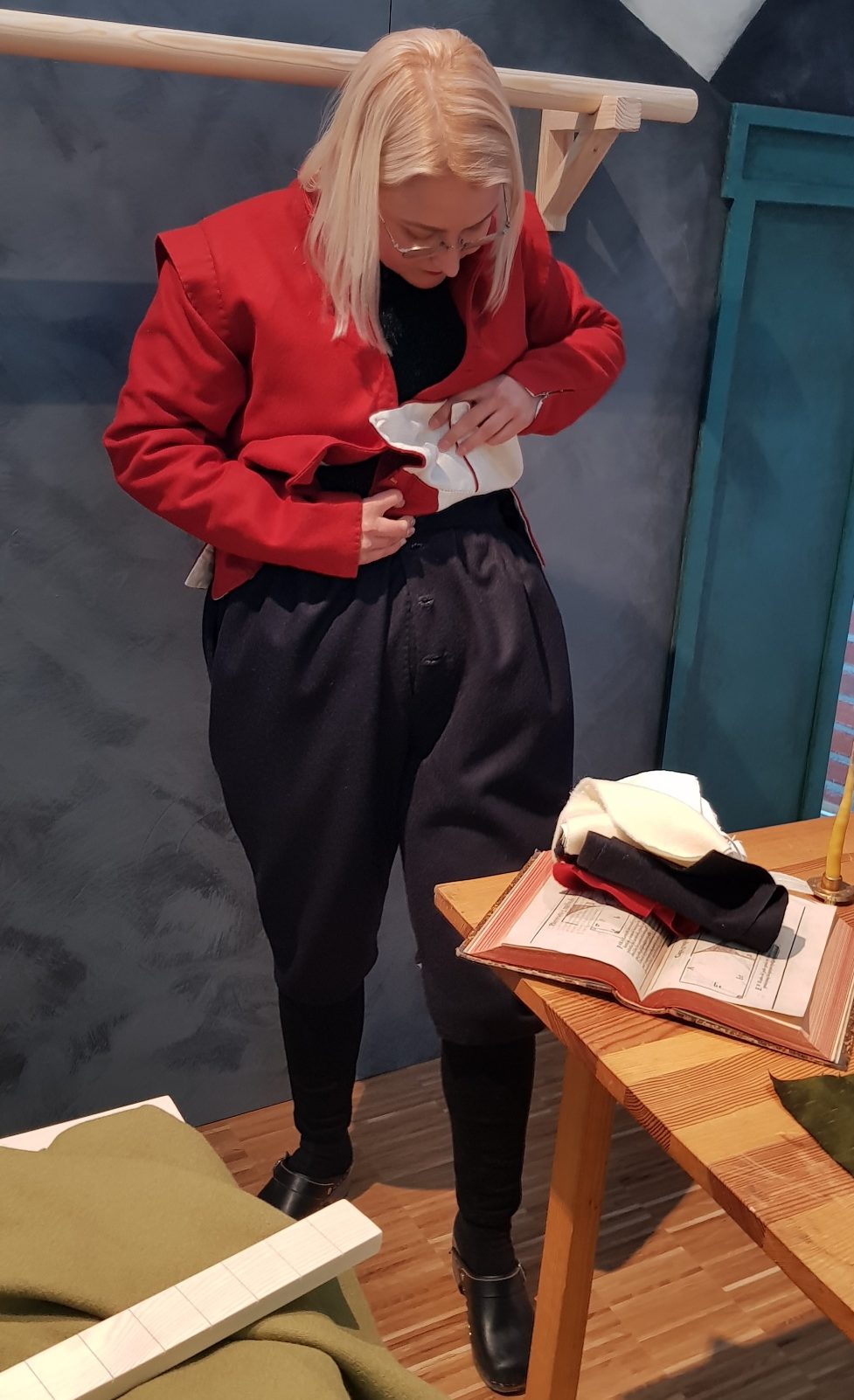

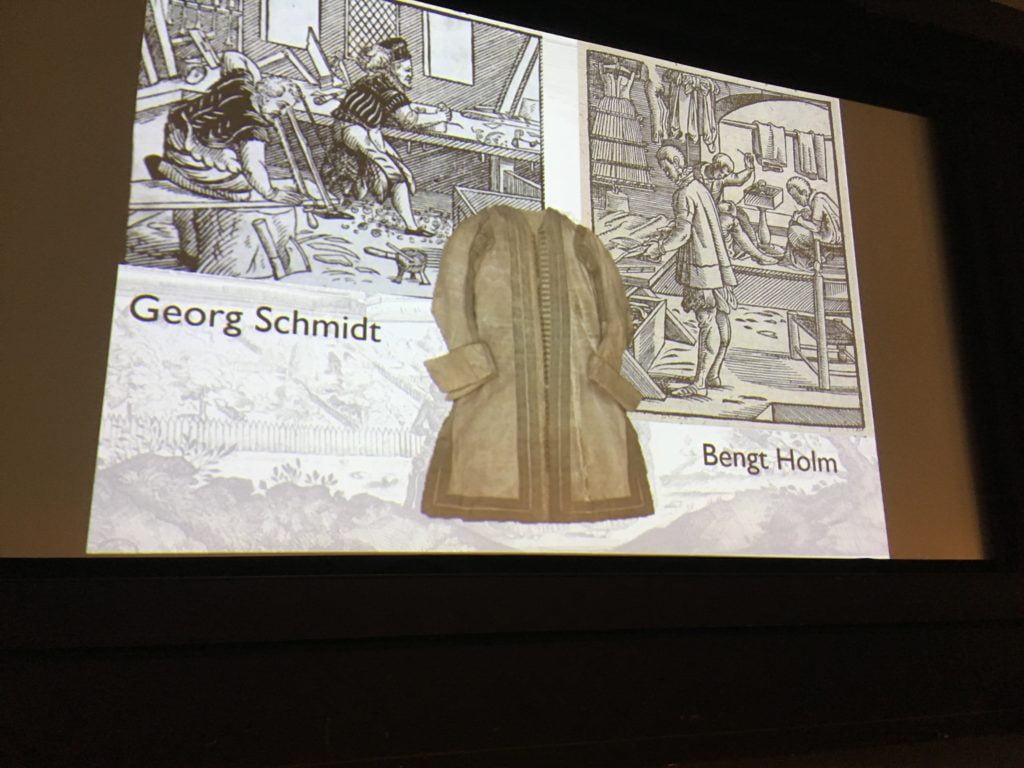

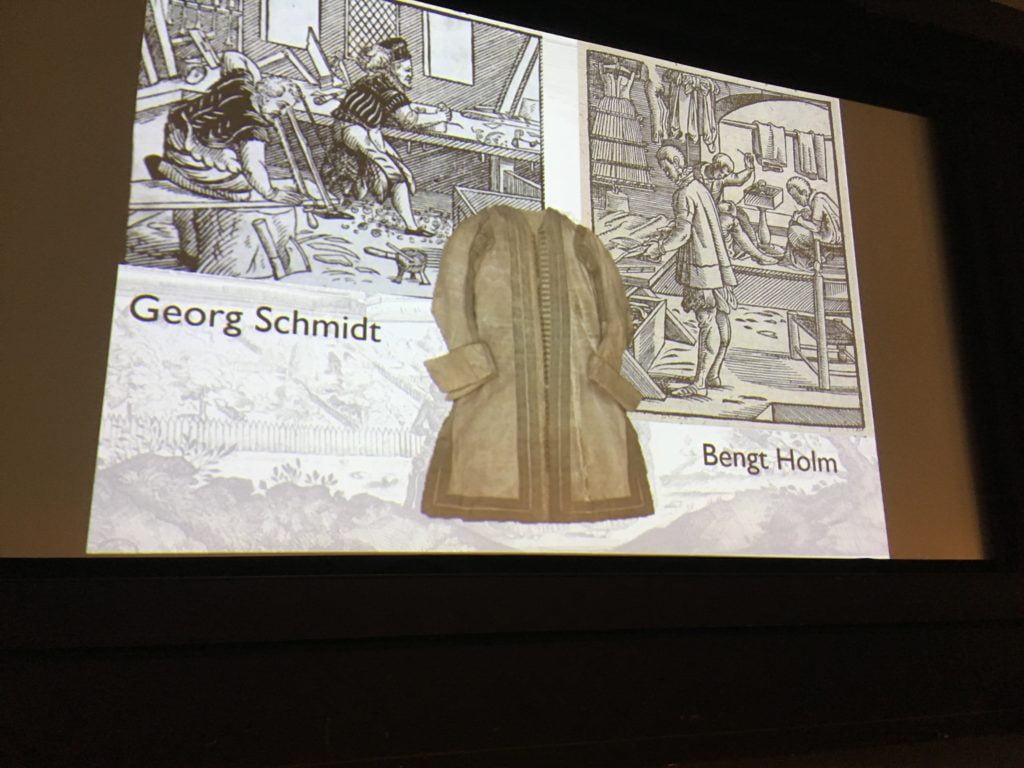

I was on the same panel as Astrid Pajur, a PhD student that the Refashioning the Renaissance team met on our trip to Uppsala University last year. In her paper, ‘Clothes, Practices, and Social Relations in Seventeenth Century Tallinn, Swedish Baltic Empire’, Astrid also spoke about the importance of social networks in relation to dress. She presented the wonderful example of an organ builder who did not feel he was provided with the outfit ‘in the latest fashion’ that he had requested from a local tailor and decided to take action against him. This resulted in a long and complicated dispute between the two men, each leaning on their colleagues and fellow townspeople for support. As Astrid demonstrated, the value of the clothes also had a social aspect, as the organ builder felt he would face ridicule and damage to his honour if he wore the unfashionable outfit provided by the tailor.

A slide from Astrid Pajur’s presentation. Photo copyright Refashioning the Renaissance Project.

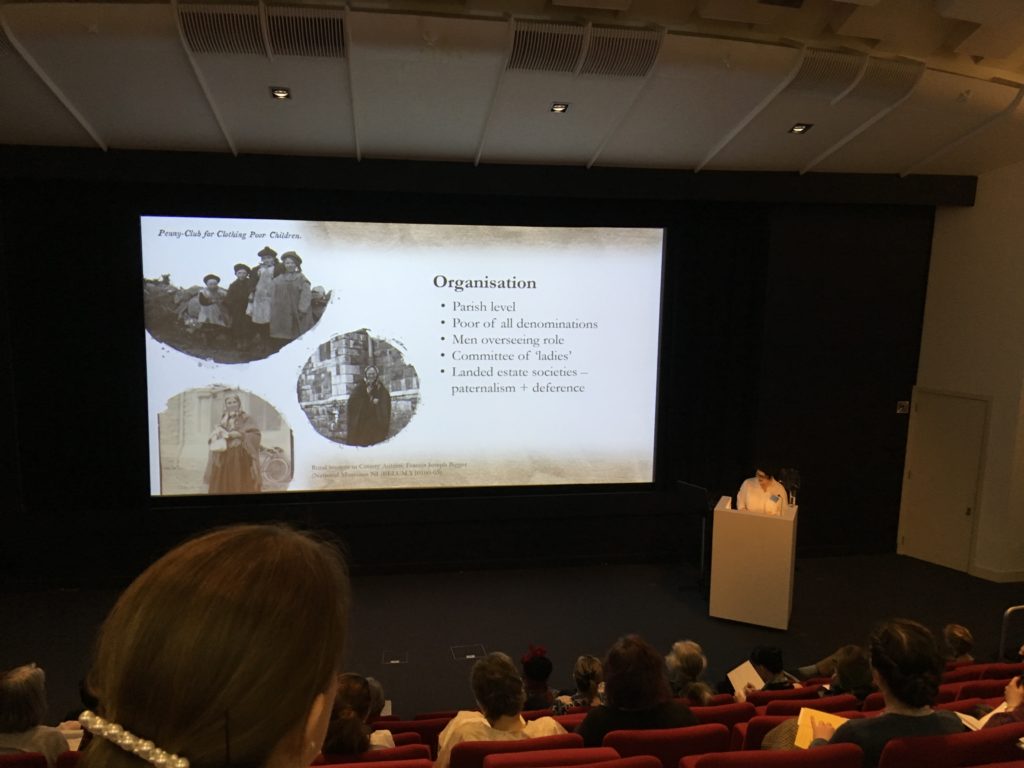

The panels in the afternoon featured presentations on a range of interesting topics, including the female suppliers of clothing and accessories to the nineteenth-century French court, metallic bobbin lace from Sweden’s royal wardrobe, dress for cycling in the First Brazilian Republic and the problem of women’s hats in late nineteenth-century American theatres. I was quite intrigued by Eliza McKee’s paper, ‘Landed Estate Clothing Societies in Rural Ulster, Ireland, 1830–1914′, which explored the dress of the poor through evidence around clothing clubs. As part of these clubs, the wives and daughters of wealthy landowners brought together donations that provided their impoverished tenants with clothing, especially for winter. The details of these garments and lengths of fabrics were captured in detailed account books and registers kept by the club members, monitoring this important aspect of their tenants’ lives.

Eliza McKee presenting her research. Photo copyright Refashioning the Renaissance Project.

I also saw some interesting connections between my paper and that of Leren Li, titled: ‘Japanese Boro and the Designing of Frugality in Contemporary Fashion’. Leren explained the Japanese terms boroand boroboro, which refer to tattered garments and soft furnishings. In the past, when many Japanese people lived in rural areas with very little money, women mended and created new garments clothing through the recycling of pieces and patches from other textiles.

Robe worn by a Japanese peasant or fisherman and pieced together with indigo-dyed cotton, c. 1850-1900. Cotton, 115x120cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

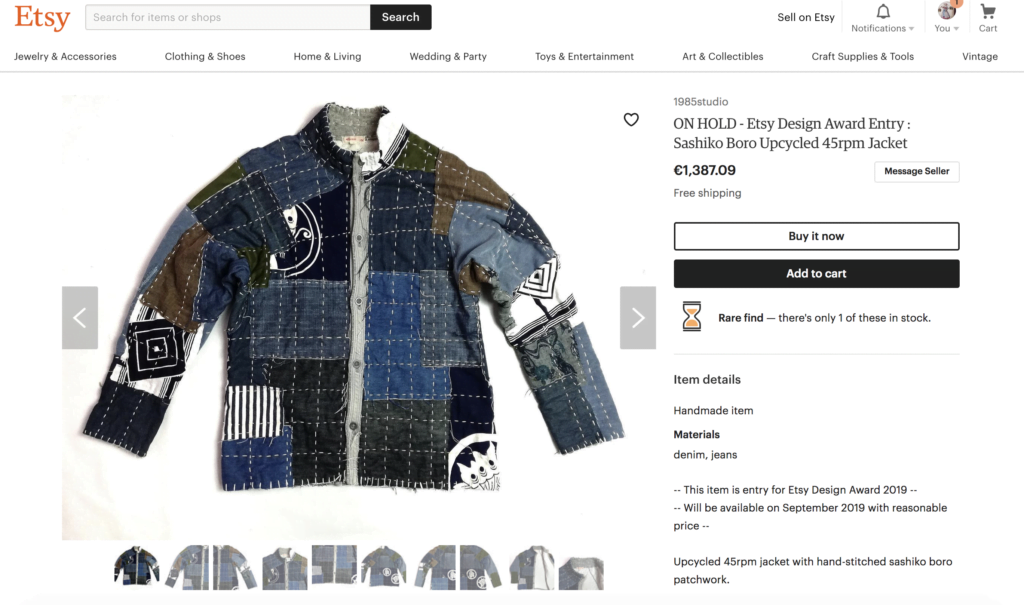

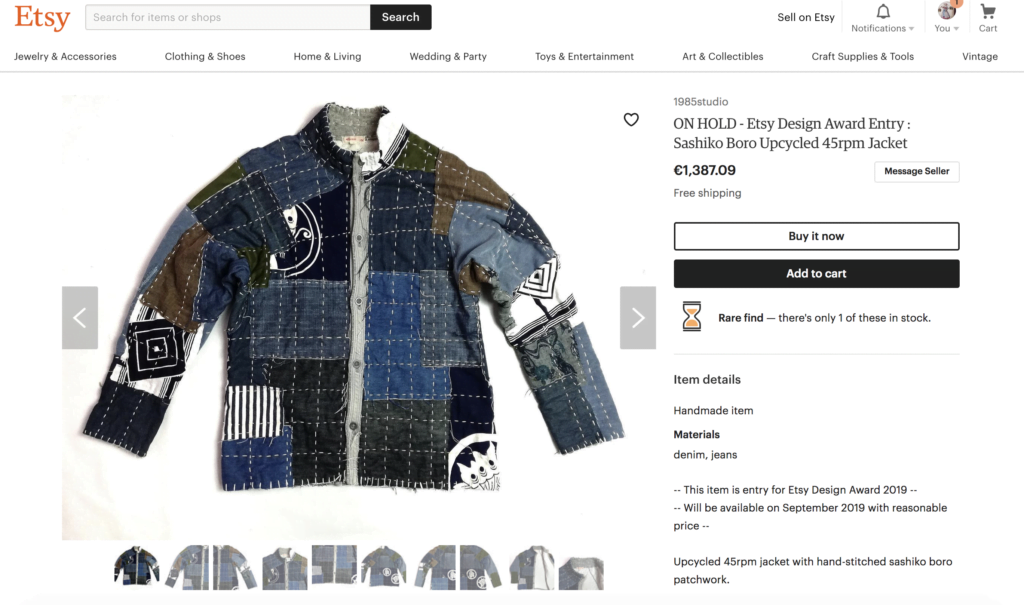

Today, at least in urban centres in Japan but also Europe and North America, garments are still patched up in this way, but for reasons of fashion rather than poverty. For instance, the jacket pictured below, which features hand-stitched ‘boro’ patchwork, can be purchased for just under 1400 Euros on Etsy! Leren also spoke about workshops that teach people to mend their clothing in the borostyle, and in some instances, participants bring new t-shirts with purposely cut holes, which they patch with vintage fabric.

Although the papers presented at the conference were many and diverse, they were unified by the importance all placed on how meaningful dress is and was in the past. Each paper, in its way, highlighted the multiple ways that different people and groups develop or derive meaning from clothing – whether their own, that for their families, friends or customers and through production, consumption or even just spectatorship. Most importantly, as each paper demonstrated, clothing takes its multiple, complex meanings from the social realms in which it lives.