To remove Ink, Cherry Juice and Other Stains and Spots

In 1648 the book Flora Danica, det er: Dansk Urtebog. (Flora Danica, what is: Danish Herbal book), was published. The author of the book Simon Paulli (1603—1680) was a Danish doctor, botanist and anatomist. From 1643 to 1639 he was a professor of medicine in Rostock and in 1639 to 1648 he worked as a professor of botany, anatomy and surgery at University of Copenhagen. In 1650 he became a physician at the court and later on he became the private physician to the Kings Frederik III (1609—1670) and Christian V (1646—1699).[1]

Flora Danica was commissioned by Christian IV (1577—1648) in 1645 while he wanted a book for the general population.[2] This can also be seen in the introduction of the book where it is noted how the book was aimed for people such as ‘the ordinary Man who lives in the country./ who does not always have resources or money to seek Doctors against various illnesses and incidents…’[3]

The book is divided in two sections containing 384 plants: the first part describes information such as name, appearance, place and use, whereas the latter part contains woodcut illustrations of the species.

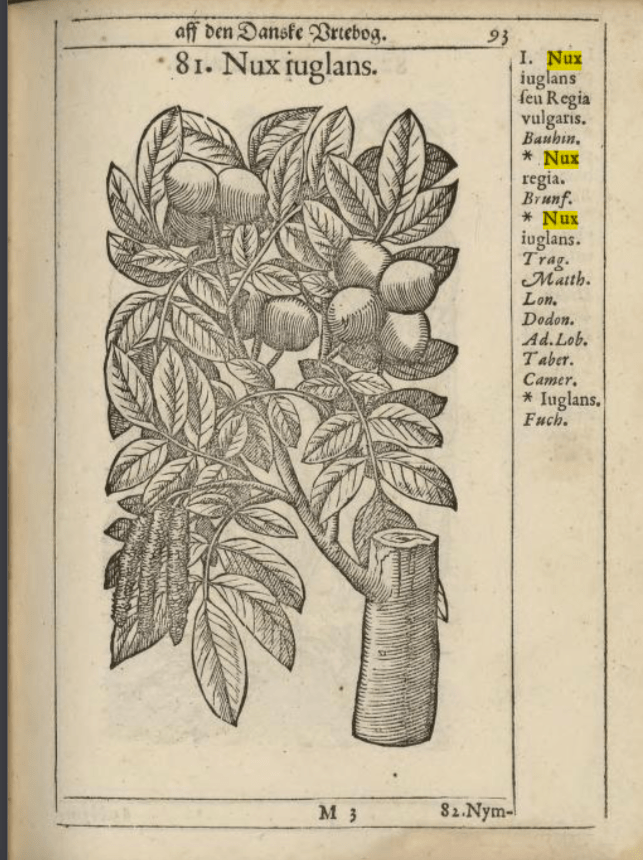

Although much of the information in the first section of the book relates to health and medicine, Paulli also offers tips on caring for textiles. For example he warns readers about walnut trees advising them not to:

… hang your [linen] Goods under Walnut Trees to bleach or dry: while the drops that fall down from the Walnut Trees / will stain the linen garments/ and the same stains will not go away easily It can therefore be concluded/ that Walnut trees are not beneficial in bleach fields.[4]

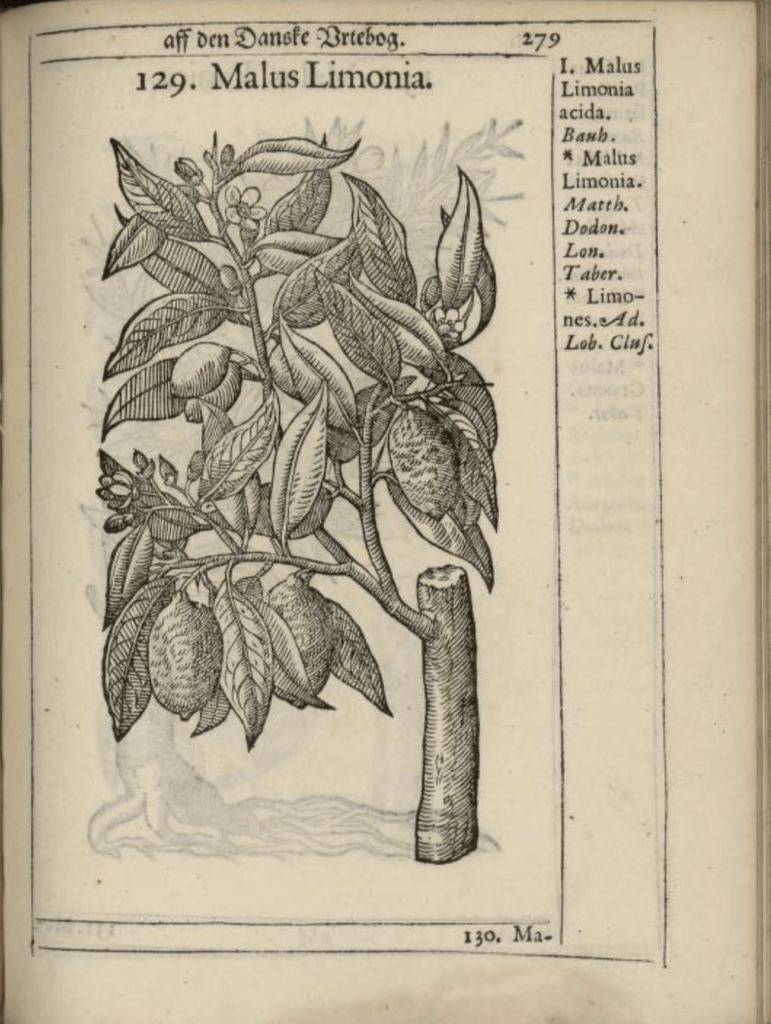

But in case of having stained garments, Paulli also explained how juice of Malus Limonia, lemons, could work as a stain remover:

With this same juice distinguished women also care for cloths and other linen garments by applying [it] / when they have Ink / Cherry Juice or other alike are becoming stained and spotted: Then spread it [the fabric] out / and keep some lit Sulphur matches underneath / and if the spots are not too old/ then they will vanish with this Art.[5]

This was not the only purpose for lemons, which could help with several medical problems such as rotten teeth caused by scurvy, and were used in ointments against scabs and itchiness. The peel of the lemon was also advised to be used as ‘winter room’ refreshers in fine inns. The peel should be boiled in a pot or put in a fire pan and when soaked in rose water before boiling it would leave a ‘delightful scent’ so new guests could feel ‘recreated and be refreshed’. A sweeter scent could be achieved by adding nutmeg and Indian cloves.[6]

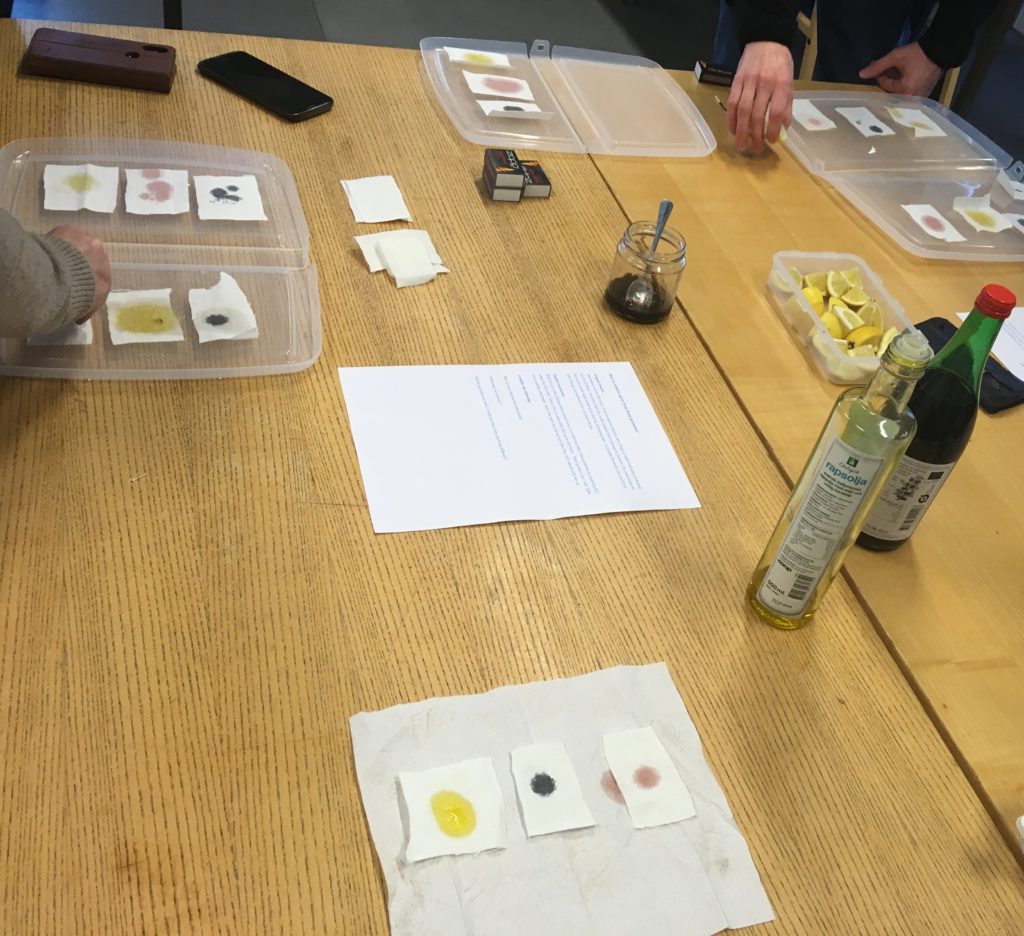

This stain removal instructions given by Paulli were tested on the 28th of November 2019, when I arranged a session for the students participating in the course ‘Textile Archaeology – A Hands on Approach’, based at the Centre for Textile Research and Department of Archaeology at the University of Copenhagen.

For the experiment I tried to use as authentic materials as possible, however some compromises were made. I for example used bleached medium-weight machine woven linen and in case of using svovlstikker (Sulphur matches), I used modern matchsticks. The svovlstikker (Sulphur matches) mentioned in the recipe would have contained smelly and poison Sulphur and would not have been self-igniting as the matches we use today.[7] I furthermore acquired organic unsweetened cherry juice made from sour cherries, organic lemons and ink, made from oak galls, iron sulfate and gum Arabic. Furthermore, I brought some organic cold pressed sunflower oil to test if the recipe could remove oily substances.

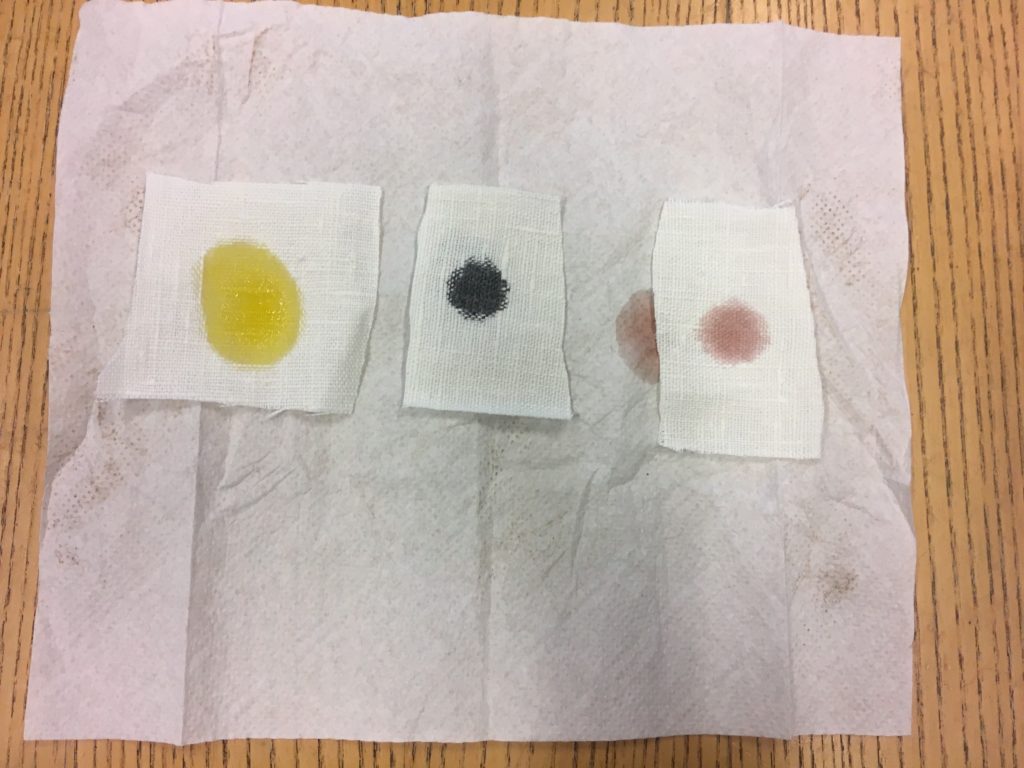

We followed Paulli´s instructions, applying cherry juice, ink and oil on linen fragments. Shortly after we applied the lemon juice and lit a matchstick underneath. After the samples were rinsed in water and left to dry.

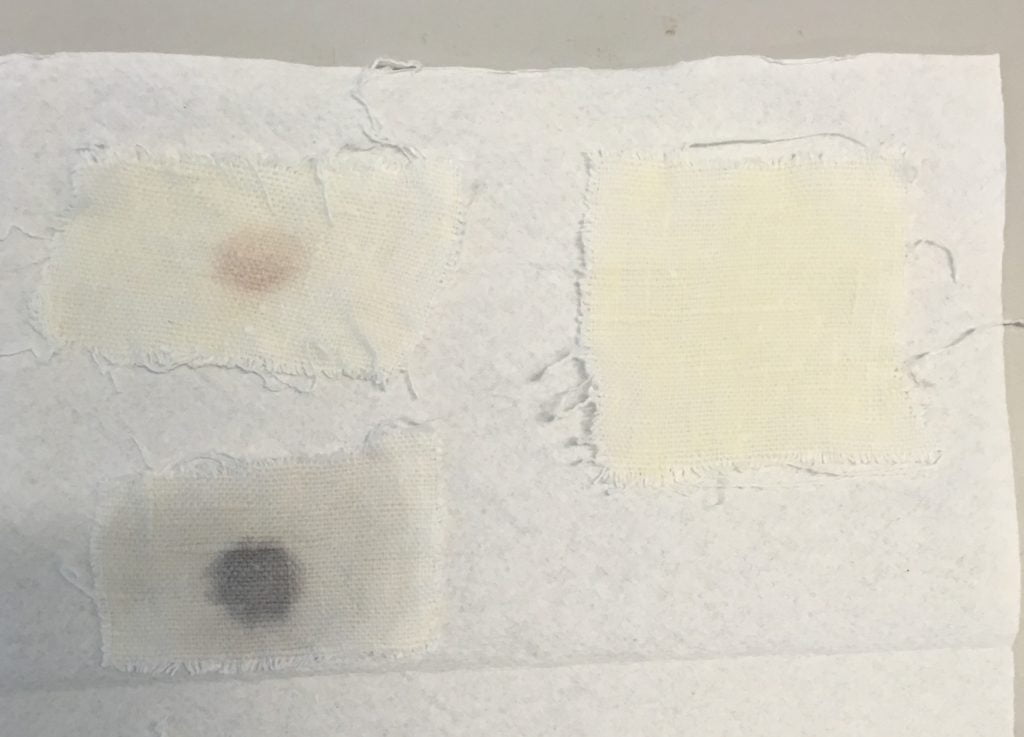

Before and after pictures of the stained linen fabrics. Top: before the stain removal was applied: oil, ink and cherry juice. Bottom: after the stain removal process: cherry juice, oil and beneath cherry juice is ink.

The recipe did not remove the stains completely, but the stains were improved, and you can imagine, especially in the case of cherry juice and oil, that if the fabric was bleached afterwards it would almost become unnoticeable. In all, I think the experiment was a success, not only in terms of trying out the recipe, but also in introducing the students to how historians can make use of texts to reconstruct or materialize practices or processes, in this case contemporary textile cleaning practices. It also shows how we can get a deeper understanding of how people might have cared for their textiles and to what extent it worked.

[1] http://denstoredanske.dk/Natur_og_miljø/Botanik/Botanikere_og_plantegeografer/Simon_Paulli, Salmonsens Konversations Leksikon, Christian Blangstrup, Bind XVIII Nordlandsbaad—Perleøerne (Copenhagen: A/S J. Schultz Forlagsboghandel, 1924)., 993

[2] http://denstoredanske.dk/Natur_og_miljø/Botanik/Botaniske_haver%2c_museer_og_foreninger/Flora_Danica

[3] Flora Danica, see introduction

[4] Flora Danica, p 94 Y

[5] Flora Danica, p 279 Y

[6] Flora Danica p 279 S – V, Z

[7] Self-igniting matches as we know of today were first invented in the 19-century. Svovlstikker ( Sulphur matches) is mentioned in Danish dictionaries from the sixteenth-century referring to them in Latin as Sulphurata, Fomes Sulphureus and Sulphuratum. Sulphur matches were first mentioned in England in the 1530s, see e.g. Nell DuVall, Domestic Technology: A Chronology of Developments (Boston: G.K. Hall & Co, 1988), 271.