At home with a tailor – a multifunctional workspace

In 1622, the tailor guild’s statutes in Elsinore stated that customers should ‘get their finished work in agreed time’ and tailors were not allowed to have unfinished work laying around for too long. If the tailor was too slow, the owner of the commission could complain to a guild meeting, and the master had to pay fine not only to the guild, but also the the guild’s poor. The only acceptable reason for slow work was ‘illness or other legal matters’.[1] In case of complaints from customers, the work was to be inspected by two other master tailors, and if the garment was found ‘poorly sewn’, damaged, or if the tailor had ‘taken too much off than necessary’, the tailor had to keep the work and pay the expenses himself.[2]

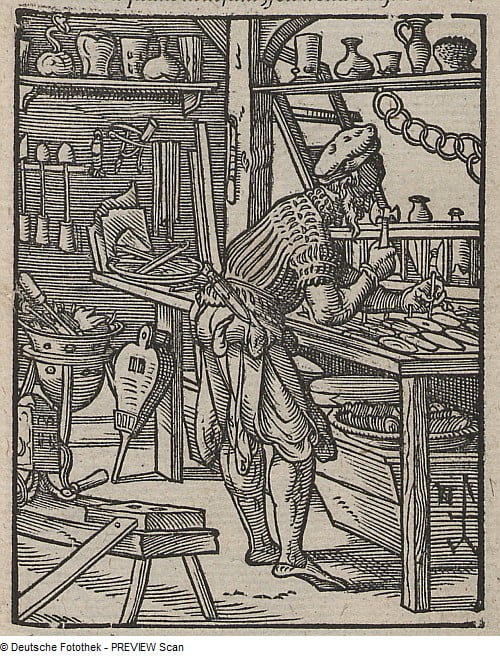

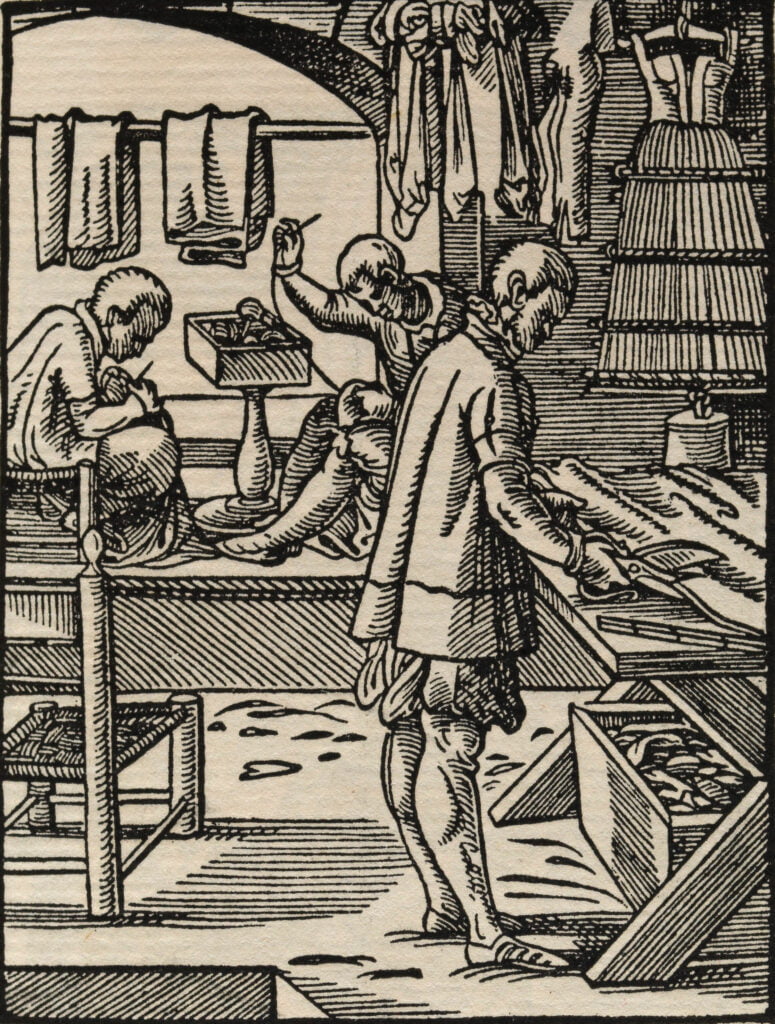

A tailor, from Das Ständebuch by Jost Amman, 1560. Image: Wellcome Collection.

These passages originate from the tailor’s guild statutes in Elsinore and illustrate how tailors in Elsinore aimed to be reliable, trustworthy, and perform their best work. But the 1622 statutes do not only state the process of working as a tailor, they also regulated how finished garments should be sold in town. According to the statutes, a tailor could only sell garments from the ‘one place where he himself lives’.[3] This could explain why the tailor Jacob Robbersen, who was a member of the tailor’s guild, had a wooden board hanging outside his door, but other than that artisan inventories do not give much evidence on the physical space around the production of clothing.[4]

The place of work

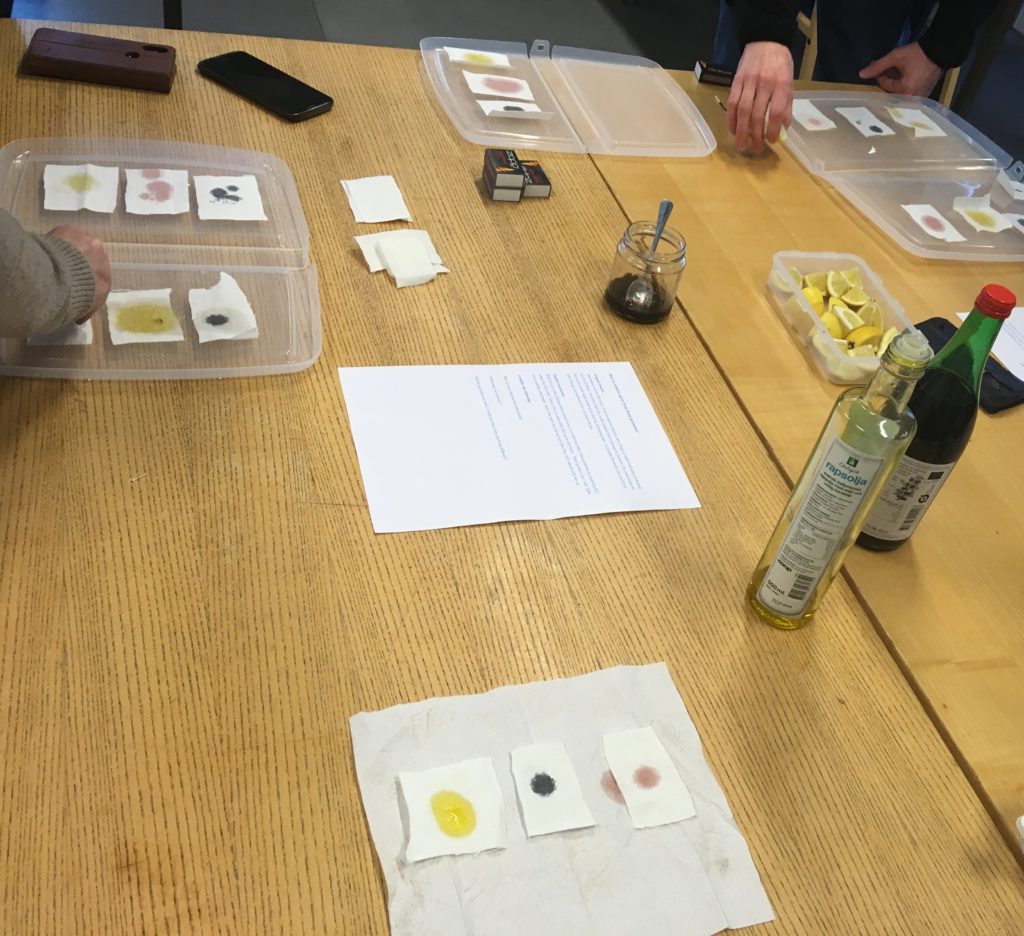

In light of the Refashioning the Renaissance, inventories are especially good at illustrating artisan’s personal wardrobes. However, a unique inventory from a tailor in Elsinore gives us also insight into the work environment around the production of clothes.

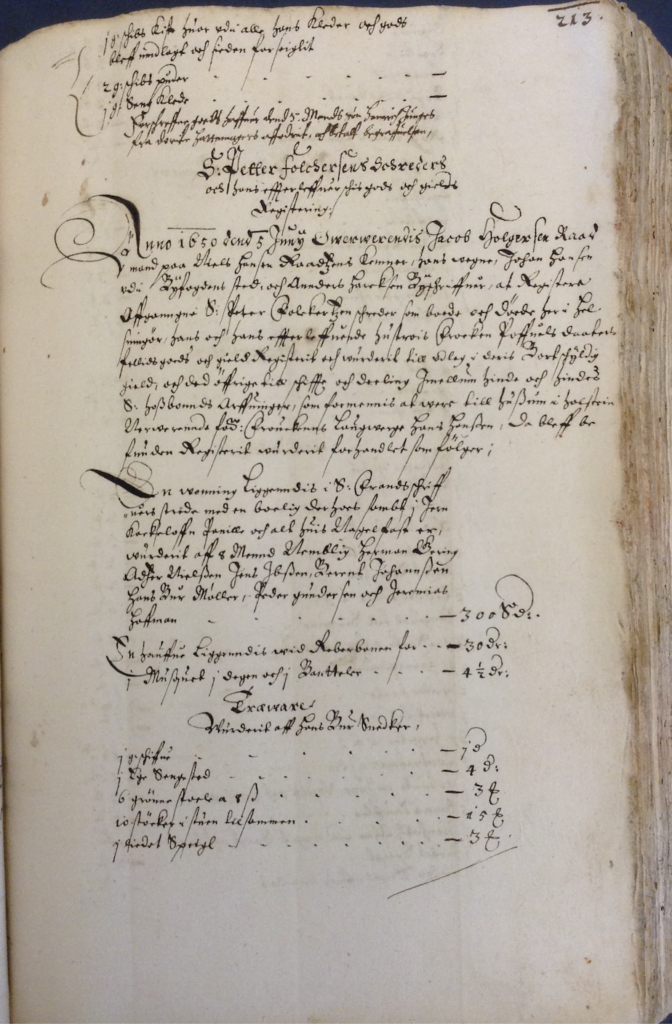

An insight into a tailors work environment in the household is demonstrated in the inventory of Peter Folckertzen, a tailor whose inventory was drawn up on a summer day in 1650.[5] The inventory does not only give us an understanding of the private possessions found in the household, but it also sheds light on the space that they occupied when the inventory was made. This can give us a sense of the daily life in the household, and how a tailor’s work was performed in this period.

From the inventory, we see that prior to his death Peter lived in Elsinore, where he owned a property in Frands Skriverstræde and a garden in town. The house consisted of several rooms, including a small chamber, a steggers (a sort kitchen), sallen (a larger room) and a basement that kept six empty beer barrels. Peter did not live in the property by himself. He oversaw a household consisting of himself, his wife, their children, and his journeymen who also lived in his household. From the inventory we also get information on his family relations as it was noted that Peter’s heirs were in Holstein.

A room for daily life?

According to the inventory, it looks like sallen was a central space in the house. For example, it housed materials for household work, such as spinning: two old rock (spinning wheels), two haspel (thread winder), and a garnvinde (yarn winder). But it also seems to be the place where Peter and his two journeymen worked during the day producing clothing. This is illustrated by the furnishing of the room, which included two shredderstoele (tailor chairs) and a verckfad, an artefact to store needles and threads. Furthermore, it contained an elaborate measuring stick, an alen (ell-wand) that was made of ebony ‘with some silver and bone’, three tailor’s scissors, one for each of his journeymen and one for himself, and a prenn, an awl to create holes in fabric. There were also four old særke (shifts), but nothing suggest that these were commissioned work.

Figure 5: The Tailor’s Workshop, 1661, Quiringh van Brekelenkam. Image: Rijksmuseum.

The room was not only reserved for work, as the furniture of the room suggest that it had a multifunctional purpose. Children and apprentices slept there, and closets, benches, and leather chairs indicate that it was a central room for daily life. Being both the place for work and sleep, it is noteworthy that sallen was the most decorated room in the house, which could suggest that this was also the room where guest and customers could be received. On the walls were five unidentified but valuable contrafeier, (often a portrait), and an old piece which was described as ‘about Juno, Venus and Pallas’. This painting hung together with five other small tauffler (paintings). It is likely that the painting named ‘about Juno, Venus and Pallas’ was similar to the painting with the same title, painted by Hans von Aachen in 1593, that depicts the three goddesses (figure 6). It was not only paintings that adorned the room. Hanging above the table was a small angel, and on the wall was a small mirror. Sallen was also the place for reading, writing, and entertainment, as it housed items such as 12 small old books, a Luther’s bible in German (folio), a board game, and an inkhorn.

Pallas Athena, Venus and Juno, Hans Von Aachen, 1593. Image: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Other inventories give evidence on tools and property in relation to the craft, and few other inventories give evidence of textiles and unfinished work the tailors left when they died. However, in comparison they do not give such a vivid insight into the material surroundings of artisans working from home. Nevertheless, all these small evidences allow us not only to get insight into the household of artisans, but also—more importantly—show how work, such as making clothes, was an important task in the household occupying the central room in the house.

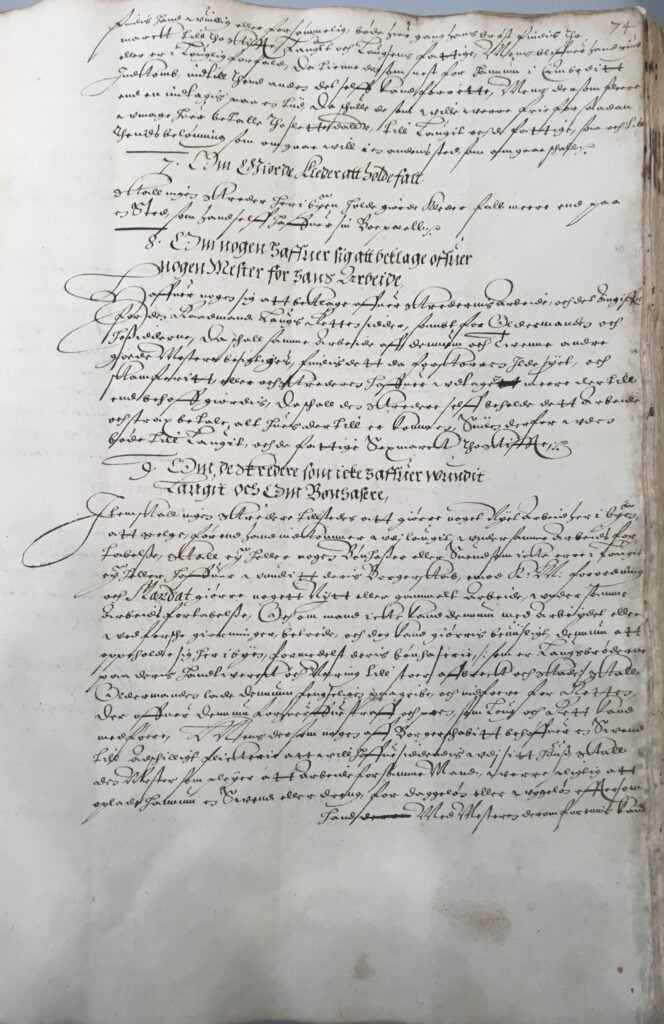

[1] Danish National Archives, Helsingør Rådstue, Tegnebøger 1626-1641, 74 v

[2] Danish National Archives, Helsingør Rådstue, Tegnebøger 1626-1641, 74 r

[3]Danish National Archives, Helsingør Rådstue, Tegnebøger 1626–1641, 74 r

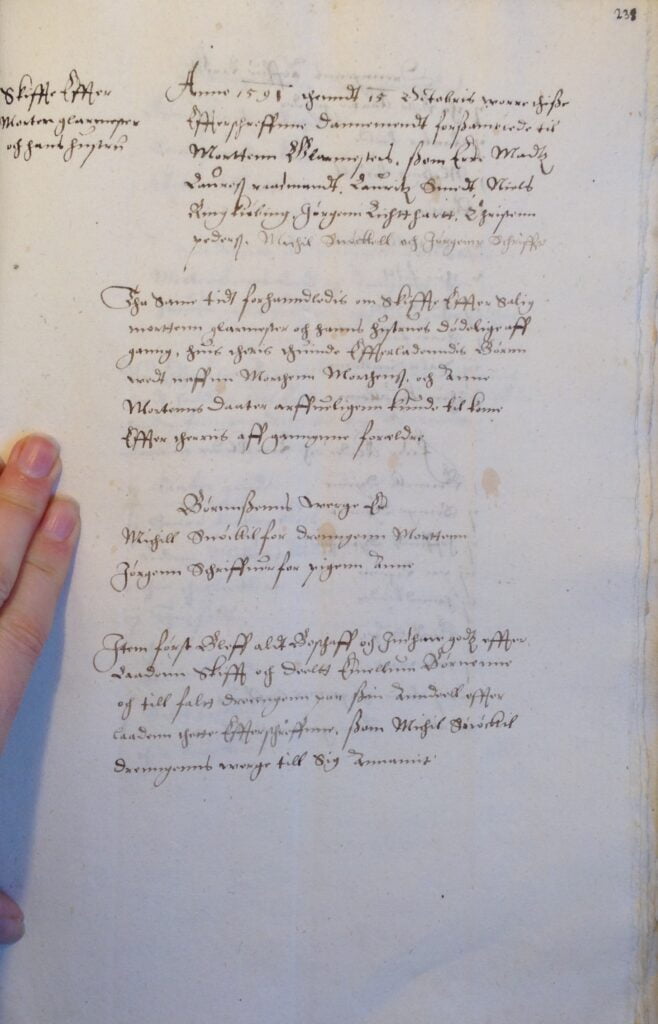

[4] Danish National Archives, Helsingør Byfoged, Skifteprotokoller, 1621–1625, 521 v

[5] Danish National Archives, Helsingør byfoged, Skifteprotokoller, 1648-1650, 213 r – 215 v