Considerations from the Venetian State Archive: Reflecting on Data

By Umberto Signori

Umberto worked with us for two months, assisting Stefania Montemezzo in the data standardisation and transcriptions for the database. Read more about the database on Stefania’s project page.

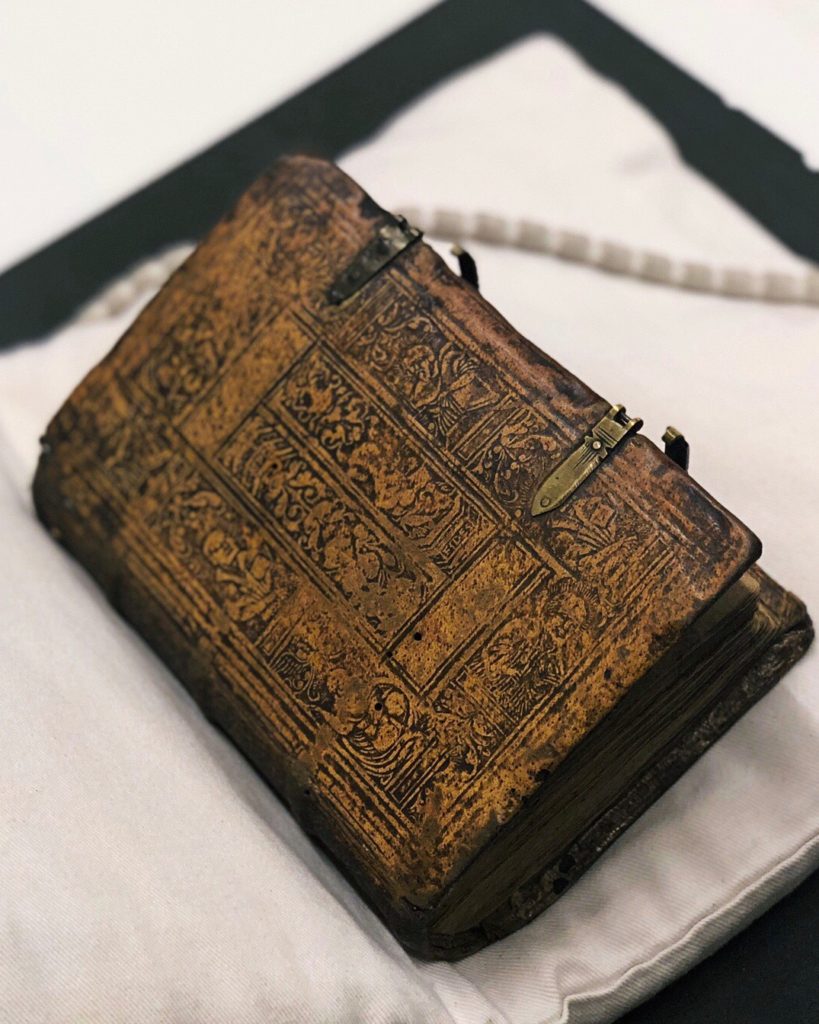

Inventory of Francesco di Giosafa, merciaio (5 January 1551).

Like many kinds of historical documents, post-mortem inventories from the early modern period might at first sight be taken for handy repositories of straightforward facts. The use of “object-based” research methodologies, which are traditionally used in elaborating such inventories, has been a tendency of scholars of consumption practices to identify a “modern” type of consumer, and to expand our understanding of the emergence of various “consumer societies” along with expanding connections across the globe. According to this point of view, probate inventories are utilitarian documents that seem to have no hidden motives or ulterior designs to stand in the way of modern data-mining operations, whether large or small in scale.

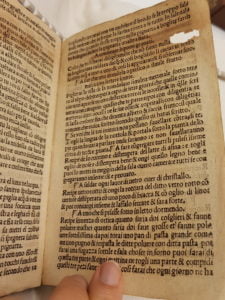

Indeed, this was my first approach in working on the inventories kept in the Venetian State Archive which were used for the database. As an expert researcher told me at the early stages of this experience, making a database may get you the buzz at the beginning, but it requires a lot of patience in the end. In fact, when I started, I was thrilled by the idea of understanding how a method-oriented database works (something that, in my previous attempts to work out a proper system of categorisation for my research project’s database, I had found very difficult). Eventually, the actual data transcription and standardisation for the database is a bit laborious and time-consuming. The final outcomes of such a quantitative approach can be very rewarding: they can show if the members of the middle ranks of Venetian society (especially the artisans and the shopkeepers) were fashionable consumers, up to date and demanding or not. They can also demonstrate whether the evolving tastes of Venetian consumers for fine things pervaded many levels of society. Yet, the stages that precede the final one may appear quite static and monotonous. Are the final outcomes of the database the only thing that really matter?

Even though it appears that an inventory can give us only a static picture of a patrimony at a precise moment in time, it is important to realize that the “reality” at stake in the inventories was a fabrication: they functioned as a rhetorical tool. Thus, the inventories do not state the reality sought by the historians. While we were transcribing the early inventories’ data (which were all male inventories), I noticed that they contained a lot of female clothing and garments. I started to wonder what really an inventory recorded: the deceased’s properties or his own possessions? At first sight, it appears that post-mortem inventories did not distinguish the exclusive personal use of objects from the general ones. It is usually impossible to distinguish between what had been personally acquired and used by the deceased and what instead had been used by other members of his family, or had just been collected as money equivalent-objects. My main questions while transcribing were these: how did the procedure of making an inventory actually work in the Early Modern period? Did the inventories just portray in a static way objects possessed at one moment in time?

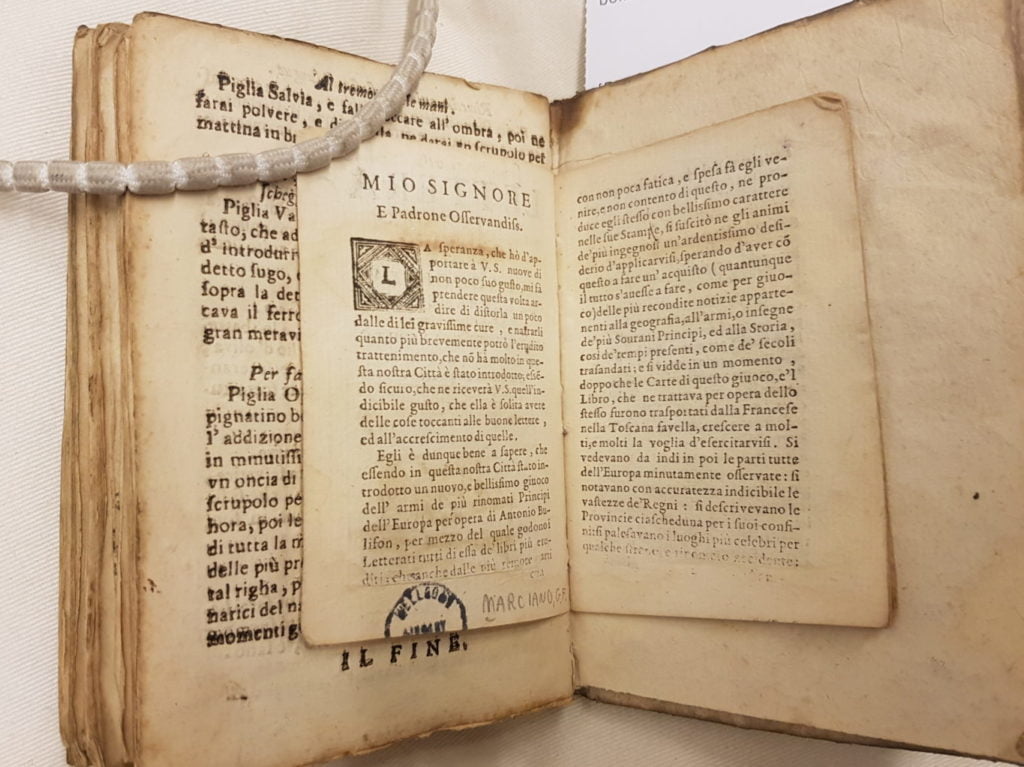

Once the transcription had been done, we started the actual data standardisation, which was more focused on cataloguing the transcribed information, including the materials, decorations, conditions, and colours of the clothing, accessories and jewellery recorded. The data recorded at this stage that struck me more was about the condition of the object: whether it was used, new, old, or broken, and whether it was pawned or not. The number of times I was recording the data “used”, “old” or “pawned” amazed me. This made me more aware of the existence of a second-hand goods market in the Early Modern Venetian society, something that I hadn’t really realized before starting this work. As many studies on second-hand exchange have already demonstrated, in Early Modern period all the items of clothing, and not only the precious ones, then, could be easily sold or pawned. Indeed, shifts in fashion, as well as the adaptability of the textiles, lining and accessories (objects which were recorded very often in these inventories), might have made this “old” items recirculation faster, and without much expenditure.

Furthermore, it is very interesting to notice that these inventories made a marked distinction between clothes and accessories which were “used”, “old” or “broken”. Before the French Civil Code of 1804, which established the absolute, exclusive and private property as the main form of property legally possible, the regime of early modern possession clearly separated property rights into two distinct levels, an eminent right and a usage right, that could be divided and attributed to several individuals. This regime of property usually accorded the primacy to the actual possession over formal deeds. This meant that, in case of disputes concerning property ownership, the real use of an object could legally prevail over the presentation of formal entitlements. This awareness is of important interest to material culture historians because it raises many new questions on the relationship between the possessors and their objects. It has been widely assumed in the consumption historiography that clothing or jewellery consumed automatically become a “possession” of someone or of a household. Certainly, that immaterial transformation from commodity to possession is what distinguished some goods as the “possessions of one’s own”. One might in fact be interested to understand whether the probate inventories, with their “used” or “broken” indications, even gave room to the possessors to prove their rights over the goods. Others might be stimulated to look more deeply in how the action of possession of individuals, who were not the full owners of the objects and who found themselves in a “delicate” situation in respect to the management of heritage, could claim their property rights.

Far from being static documents, inventories could allow us to view material worlds of artisans, workers, shopkeepers and their relations to possessions. Therefore, even during the transcription and standardisation stages the work can be stimulating and thought-provoking. Of course, so as to study the relationship between the possessors and their objects the inventories need integrating with other sources, like last wills and testaments. Despite the fact that the inventories alone cannot be enough to run out all these topics, they might constitute an extraordinary opportunity to shed light on the actors’ interpretation of material culture.

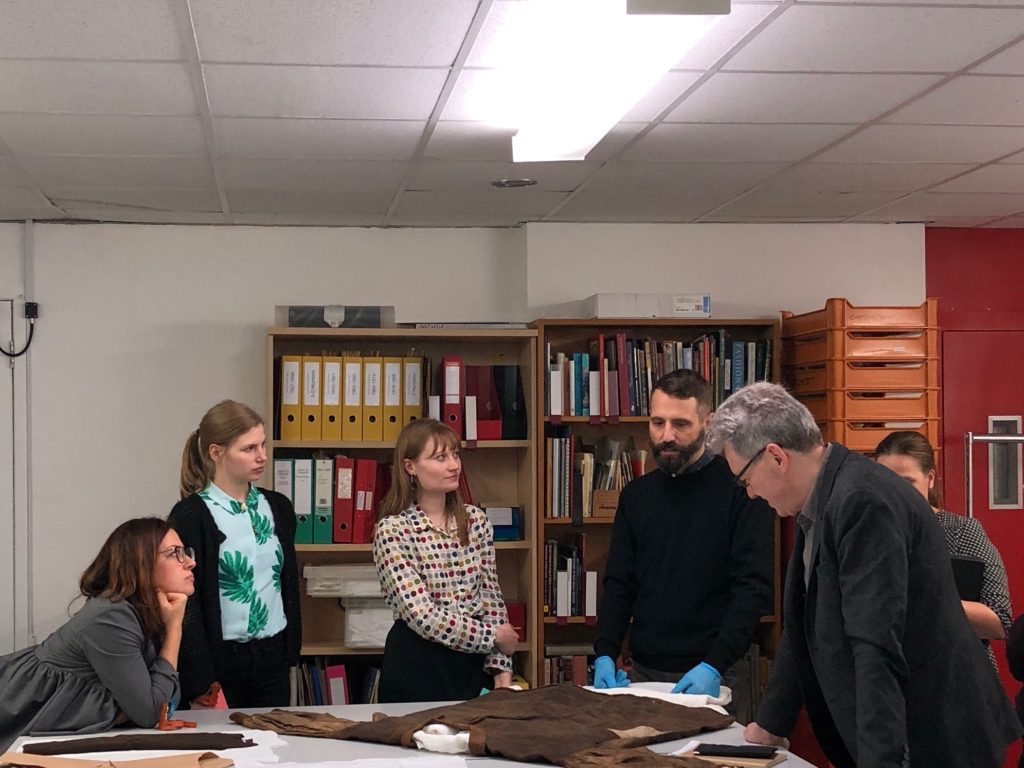

Umberto Signori hard at work with the Refashioning the Renaissance database.