The Renaissance of the Mask: from plague doctor beaks to velvet visards

2020 is unlikely to be recorded in the history books as a particularly fashionable year, as many of us have turned to neck-up ‘zoom-ready’ looks, elasticated waistbands, and slippers for comfort. But it has been sartorially remarkable for the almost-overnight success of one formerly niche accessory: the mask. As countries mandate their use in public spaces to combat the spread of Covid-19, many of us have started to wear masks for the first time, and they have become an essential part of one’s outfit. Choice of materials and maker has become important as consumers are chastised for their mask selection. Designers have capitalised on the opportunity to brand and monetise the public health crisis, while those of us with sewing skills have started cottage industry production lines to provide them for friends and family. Single use non-biodegradable masks are filling landfills by the billion, and the medical industry is asking us to reserve the highest quality of N-95 masks for healthcare professionals. Cloth masks with bright prints, beaded ties and even ruffled edges have become big business, and, you can turn to Vogue to discover the most stylish (and expensive) options on the market. Wearing – or not wearing – a mask is a political, medical, and ethical act, but it can also be a fashion statement. Masks might be ‘new’ accessories in the wardrobes of this generation, but they have a long history.

Masks for Plague

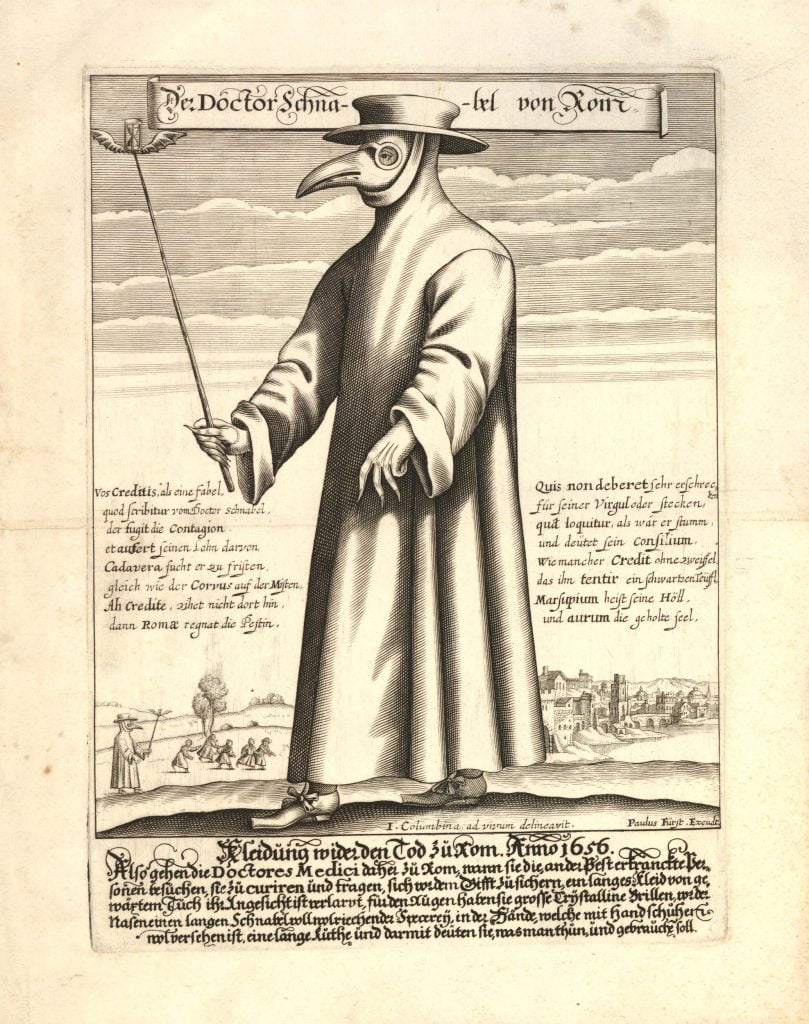

Doctor Schnabel von Rom,’ (Nuremberg: Paulus Fürst, 1656), engraving, 30.1 x 21.6cm, British Museum, 1876,0510.512 © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license

Perhaps the most iconic early modern masks are the beak-shaped facial coverings associated with plague doctors. Purportedly designed by Charles Delorme (1584–1678), physician to three French kings (Henry IV, Louis XIII, and Louis XIV), early modern PPE comprised a long overcoat, gloves, boots, a waxed leather hat, goggles, and a conical mask filled with perfume.[1] These masks responded to the belief that plague and other diseases were spread through pestilential air or ‘miasma’, which if inhaled could corrupt the body.[2] Fragrant herbs and vinegar could counteract this foul air, and so the mask’s function was to filter scents. But there is little evidence that Delorme or his peers actually used such masks, and the earliest account of the use of a beak mask comes from the 1661 Danish account of the 1656 plague of Rome. In a description of clothing worn by doctors during epidemics, the Copenhagen doctor Thomas Bartholin (1616–1680) wrote that plague doctors in Rome wore pressed linen garments in order that disease not stick to their clothes, and a beak mask to hold fragrance. A broadside depicting an Italian doctor named “Doctor Beak” (Doctor Schnabel) in this garb was also printed in Nuremberg in 1656, suggesting that this Italian plague outfit was a peculiarity in Northern Europe, and was perhaps even a source of satire. Adopted as a costume in the Commedia dell’arte and at the Venice carnival, and represented in the popular video game Assassin’s Creed, the plague doctor mask has become a culturally dominant image of the early modern mask, even if there are few contemporary sources that corroborate its use in Europe.

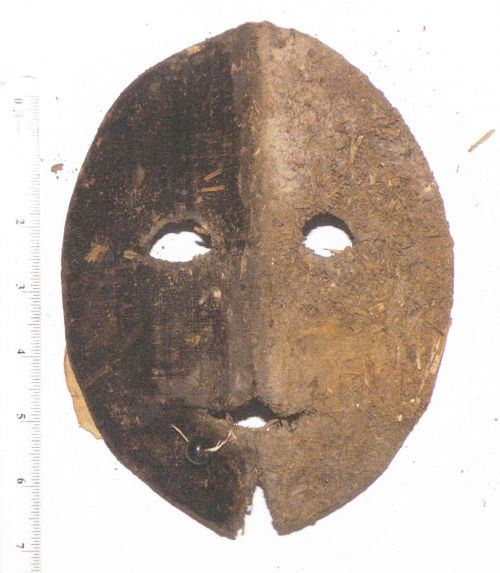

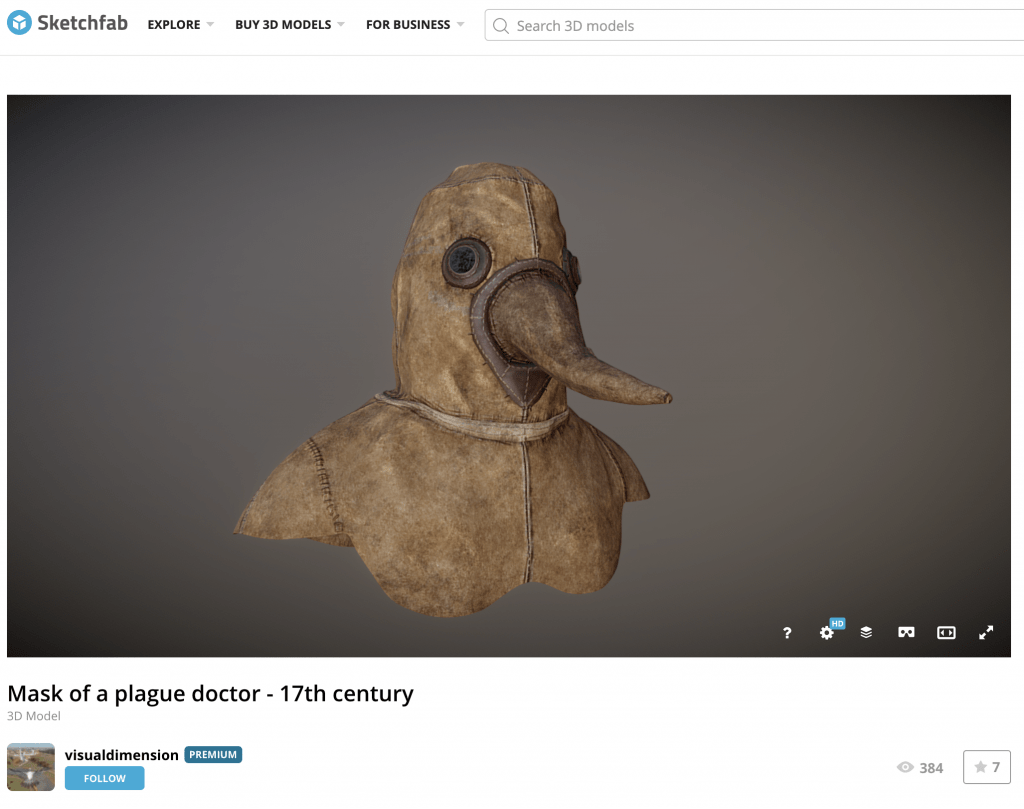

A digital reconstruction of the Ingolstadt mask. You can explore the mask in 3D here.

The material record is just as problematic. Fewer than five plague doctor masks are preserved in European museum collections, some of which are missing and all of which have somewhat dubious provenance. Masks held by the Deutsches Historiches Museum in Berlin and in the German Medical Museum in Ingolstadt are said to date to the late seventeenth or eighteenth centuries, although both were purchased in the early 2000s, and there is no evidence that these types of masks were ever used in Germany or Austria, so whether these are costumes, forgeries, or the genuine article still needs to be determined.[3]

Masks for Fashion and Protection

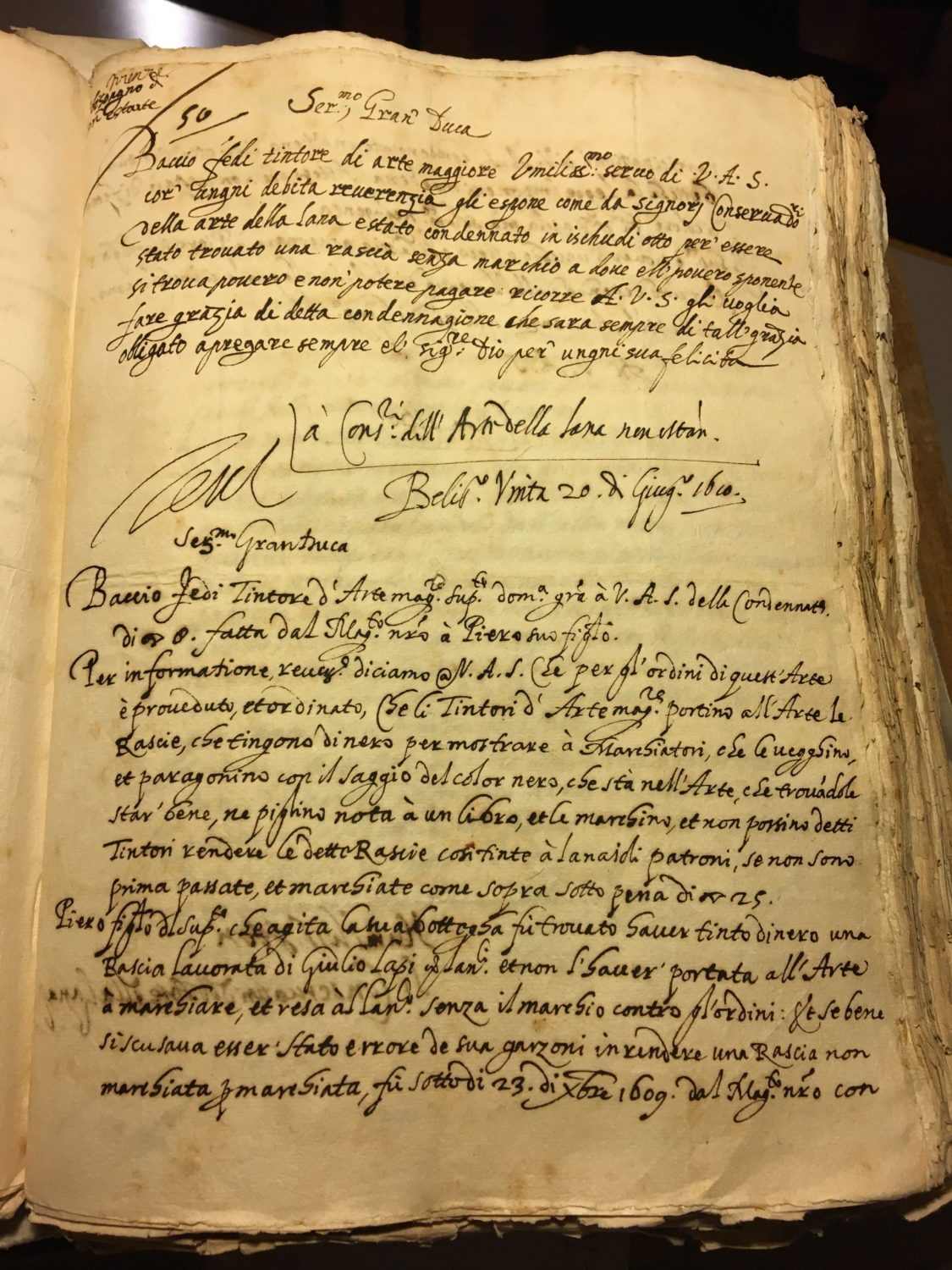

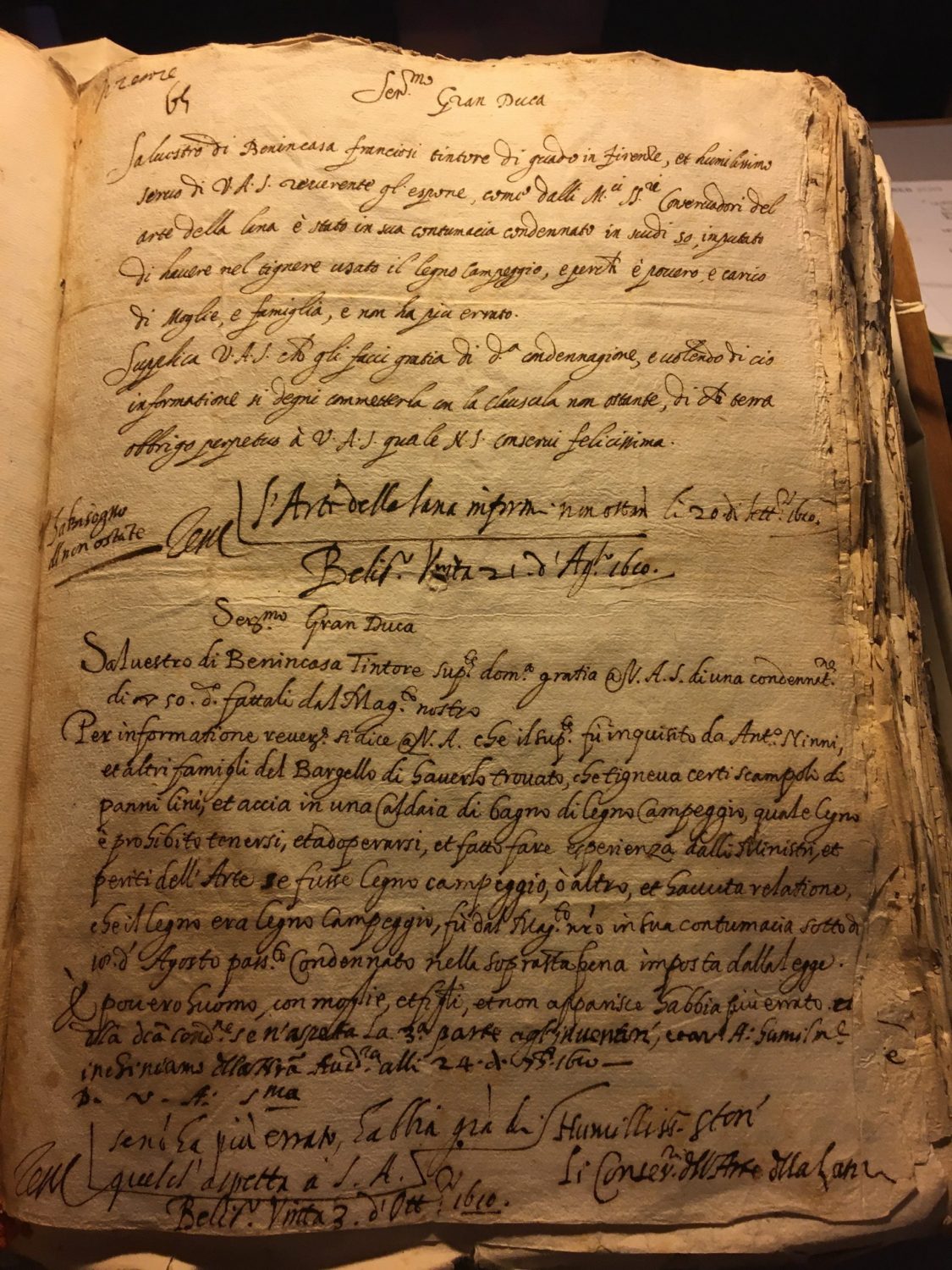

While more research is needed to sort historical fact from fiction regarding plague masks, we do know the early modern men and women wore masks for protection, style, and pleasure. Looking through inventories in the Refashioning the Renaissance database, we discover that some Italian artisans owned masks during the sixteenth- and seventeenth centuries. The 1607 inventory of Florentine carpenter Tommaso Guadagnini, for example, records that he owned a black satin mask (‘Una maschera di raso nero’) and the Florentine clog-maker Jacopo di Bastiano had a black velvet mask in his possession (‘Una maschera di velluto nero’) when he died in 1609.[4] These stylish masks were probably constructed of pasteboard or leather and covered with black silk or velvet, making them a relatively affordable and highly visible way of wearing fine fabrics without having to purchase the yards of textile required for a full garment.[5]

As Randall Holme explained in his encyclopaedic The Academie of Armory, there were two kinds of commonly worn fashionable face coverings – one kind ‘covered only the Brow, Eyes and Nose, through the holes they saw their way; the rest of the Face was covered with a Chin-cloth.’ Holme tells us that these kinds of masks were usually square with a flat top or rounded, and were ‘generally made of Black velvet,’ just like Jacopo the Clog-maker’s mask. The other type, called a ‘vizard,’ covered the “whole face, having holes for the eyes, a case for the Nose, and a slit for the mouth, and to speak through; this kind of Mask is taken off and put on in a moment of time, being only held in the Teeth by means of a round bead fastened on the inside over against the mouth.”[6] A few examples of these masks, still with their small beads attached, survive both in full size and in miniature. Any discomfort we experience breathing through a cotton mask held on with elastic is relative when you consider that the alternative could be gripping a bead between your front teeth!

Visard made of velvet and silk over pressed paper lining with a black glass bead found in the wall of a 16thC building in Northamptonshire England, Portable Antiquities Scheme, NARC-151A67.[7]

Visards were fashionable accessories, designed to hide their wearer’s face. Samuel Pepys recorded that on Friday 12 June 1663, he and his wife saw a play at the Royal Theatre. Just as the theatre began to fill up, they noticed that Lady Mary Cromwell ‘put on her vizard, and so kept it on all the play; which of late is become a great fashion among the ladies, which hides their whole face.’ Straight after the play, Pepys took his wife to the Royal Exchange shops where she purchased ‘a vizard for herself.’[8]

Worn indoors, these masks might conceal specific facial expressions, allowing their wearer a degree of privacy, but outdoors they had an additional function. Holme tells us that masks helped protect their wearer from the sun, enabling them to maintain a pale complexion.

Masks for Mischief

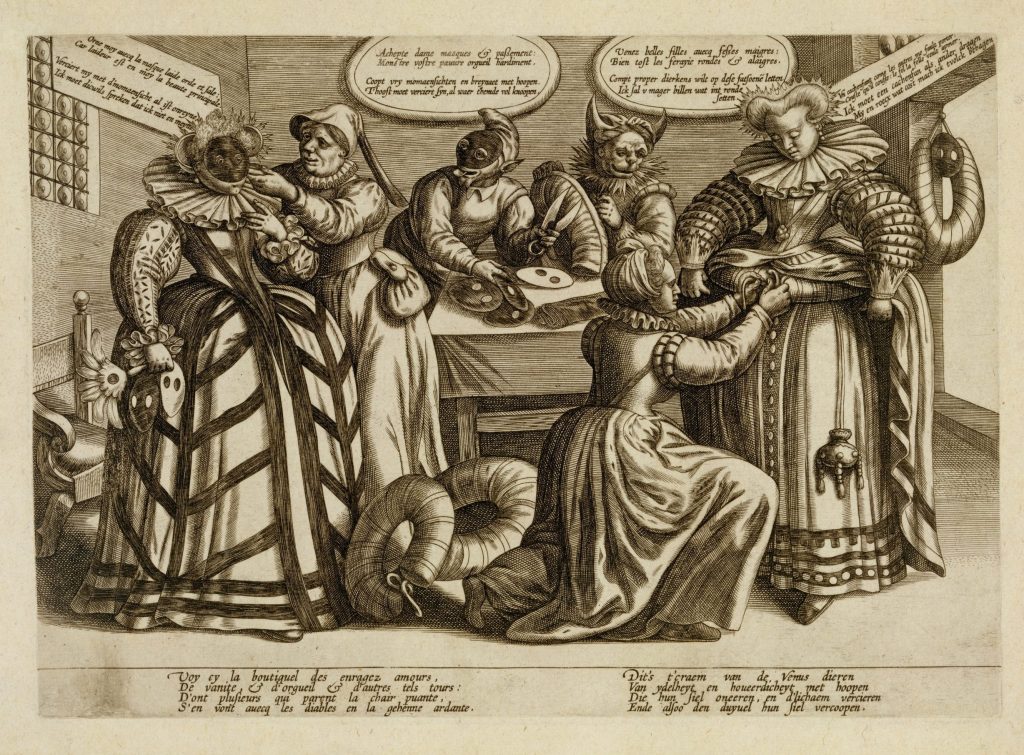

As they concealed their wearer’s face, mask-wearing was also associated with bad behaviour. Italian cities passed laws about mask wearing as far back as 1268, when people wearing masks were forbidden from throwing eggs (both real eggs and novelty eggs filled with perfume). James Johnson has argued that masking was often a conservative act, ‘preserving distance, guarding status, and permitting contact among unequals through fictive concealment.’[9] But this did not stop critics from assuming that mischief-making and mask-wearing went hand-in-hand, and in 1608, a Venetian statute prohibited anyone from going around the city either on foot or by boat while wearing a mask, except during carnival. In his 1585 description of ‘All the Professions of the World,’ Tomaso Garzoni allied masks with deceit: “Nothing here is true or real but instead false and masked.” Garzoni despaired at the way that masks enabled people to disrupt the social order: ‘Don’t you realise that masks … teach artisans to leave their workshops? And doctors to leave their studies? And scholars to pawn their books to visit prostitutes?’ Garzoni even suggested that masks were invented by Satan, who had appeared in disguise to Eve in the Garden of Eden.[10] A satirical Dutch print from c.1600 makes a similar point by depicting devils dressing women in masks and farthingale rolls. In the very centre of the scene, a masked devil holds a pair of shears and a pile of black round facemasks, allying mask-making with demonic deception.

Maerten de Vos, ‘The Vanity of Women: Masks and Bustles,’ ca. 1600, engraving on paper, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2001.341.1 (Image in the Public Domain).

Mask-making

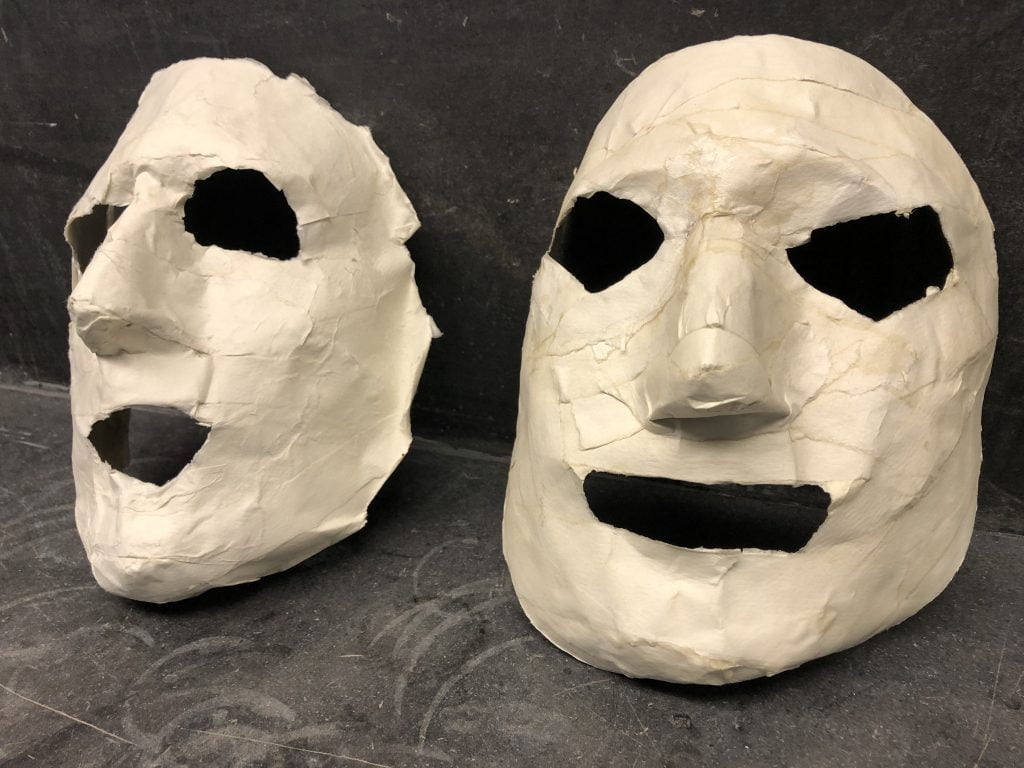

Masks were actually made by skilled professional craftsmen. In Venice, where by the late seventeenth century masks were worn in public six months of the year, the maskmakers (maschereri) were a faction of the Painters Guild and dated back to 1436. While many visards were simply made, a number of early modern artist treatises describe complex methods of making masks for costume, carnival, and for sculpture. The fifteenth century Florentine Cennino Cennini described how to take a life mask using an iron hoop, plaster of Paris, and small brass breathing tubes.[11] In his Vocabolario Toscano dell’arte del disegno (1681), Baldinucci described making masks out of cartapesta (soaked paper pulp)[12] The anonymous author of BnF Ms. Fr.640 even offered a quick method for making ‘Impromptu Masks’: ‘Mold some paper & put it on the face of somebody who is making an ugly grimace. Let it dry & take your pattern to paint from it.’[13]

Impromptu Masks made according to the instructions from BnF Ms. Fr. 640 by Juliet Baines, Lynn van Rijnsoever, Herre de Vries and Fleur van der Woude, Students in the MA Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage – University of Amsterdam Course: Kunsttechnologisch Bronnenonderzoek, Spring 2015, Instructor: Dr. Marjolijn Bol. Photograph: Tianna Uchacz.

Through our archival research, the Refashioning the Renaissance project has also uncovered a source from Venice that shows how new and old masks might be sold ready-made. A 1555 inventory of the belongings of Venetian rag-dealer Antonio Rossatti q.Bernadini reveals that he had a whole store of new and second-hand masks in his shop, including 81 ‘Sailor’s Masks,’ (mascare da matelo) 75 ‘Masks with beards,’ (mascare con la barba), 120 used women’s masks (mascare da dona usade), 41 ‘Very old’ masks (mascare strazade), 154 cut masks (mascare taiade), and 42 masks for young people (maschere da zovene).[14]

Early modern men and women wore masks despite social critique, and experimented with different shapes, styles, and materials. Now that the mask is experiencing its own renaissance in fashion, we can look to these former styles for creative inspiration. The next time you put on your cloth and elastic face mask, imagine swapping it for a mask decorated with a false beard, or popping a glass bead into your mouth and heading out the door in a velvet-faced visard.

[1] Estelle Paranque, ‘The Celebrity Physician and the Plague’, Wellcome Collection blog, 23 June 2020.

[2] Sandra Cavallo and Tessa Storey, Healthy Living in Late Renaissance Italy, (Oxford, 2013), 77.

[3] M.M. Ruisinger, ‘Die Pestarztmaske im Deutschen Medizinhistorischen Museum Ingolstadt’ N.T.M. 28, 235–252 (2020); Stefan Bresky and Sabine Witt: ‘Vorsicht, Ansteckung?’ Historische Urteilskraft, vol. 2, 2020, 94–97 and the abridged version of the article on the DHM Blog.

[4] Magistrato dei pupilli, Archivio di Stato, Firenze, 2716, 131v and Magistrato dei pupilli, Archivio di Stato, Firenze, 2716, 271r.

[5] Evelyn Welch and Juliet Claxton, ‘Easy Innovation in Early Modern Europe’, in Fashioning the Early Modern: Dress, Textiles, and Innovation in Europe, 1500–1800, ed. Evelyn Welch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 87–110.

[6] Randle Holme, The Academy of Armory, or, A Storehouse of Armory and Blazon… (Chester, 1688), Book 3, 13.

[7] For more, see here.

[8] 12 June 1663, The Diary of Samuel Pepys ed. Robert Latham and William Matthews, (University of California Press, 2000), 181.

[9] James H. Johnson, Venice Incognito: Masks in the Serene Republic (University of California Press, 2011), xii.

[10] Tomaso Garzoni, The Universal Assembly of All the Professions in the World, Noble and Ignoble (1585), as cited in Johnson, Venice Incognito, 79–80.

[11] The Craftsman’s Handbook, Il Libro dell’ Arte by Cennino D’ Andrea Cennini. Translated by Daniel V. Thompson, Jr. (New York: Dover Publications, 1960), 124–7.

[12] Filippo Baldinucci, Vocabolario toscano dell’Arte del disegno, (Florence: Per Santi Franchi, 1681), 29.

[13] Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, Jenny Boulboullé, Joel Klein, Donna Bilak, Marc Smith, and Terry Catapano, eds., Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640 (New York: Making and Knowing Project, 2020), Folio 84r.

[14] Archivio di Stato, Venezia, Cancelleria inferiore, Miscellanea, 39, 44, 1555. 12v–13r.