Representing Renaissance textures and colours digitally

By Maarit Kalmakurki

In this blogpost, I discuss how textures and colours are created as digital garments and how beneficial digital animation is for testing different Renaissance fabrics and colours. I joined the Refashioning the Renaissance team in 2019 with the aim to build a digital reconstruction of an early 17th century male doublet. This practice-led research task was highly interesting to me as it enabled me to combine my knowledge in historical dress, pattern cutting and garment making in general, as well as my theoretical and practical knowledge in digital costume design and animation. The initial aim was to build a digital doublet, present many of its complex inner layers and structures, and make an animation or video of the doublet on an avatar in a virtual environment. The nature of practice-led research allows us to discover new working methods and to make decisions along the way, which was one of the most interesting and exciting parts of this process.

The final rendition of the digital doublet was achieved through a combination of many source materials and decisions along the animation process. One of the inspirational source materials for the digital doublet was a post-mortem inventory of a Florentine water seller Francesco Ristori. The inventory described one garment; a black doublet made out of stamped mockado. The School of Historical Dress in London made a physical version of this doublet and I used the same paper patterns for the digital creation. I also studied other 17thcentury doublet patterns, sewing techniques and materials in order to make changes that were more appropriate for the digital animation. One inspirational and eye-opening learning experience was the one-week course of doublet making at the School of Historical Dress. This enabled me to understand why certain materials and sewing techniques are implemented in doublets and my task later was to re-create such features digitally.

The starting point of the digital animation is based on patterns. In the case of a doublet which includes several layers of fabric and additional supportive materials sandwiched between the lining and main fabric, I multiplied the patterns to gain the same amount of pattern pieces as there would be in a historical doublet. Once the patterns are multiplied, they literally fly in the digital space (Figure 1) before assembling them on top of the avatar body. The patterns are colour coded according to what material they are made from. Digital material behaviour and texture are interesting as everything can be adjusted in the animation program. Fabric thickness, weight and sheen can all be controlled in quite some detail with a click of a mouse. This aspect proves to be one of the most beneficial aspects of digital animation.

Figure 1. This image shows how digital patterns literally fly in the digital space before they are assembled next to the avatar body and simulated as a garment. Screenshot by Maarit Kalmakurki.

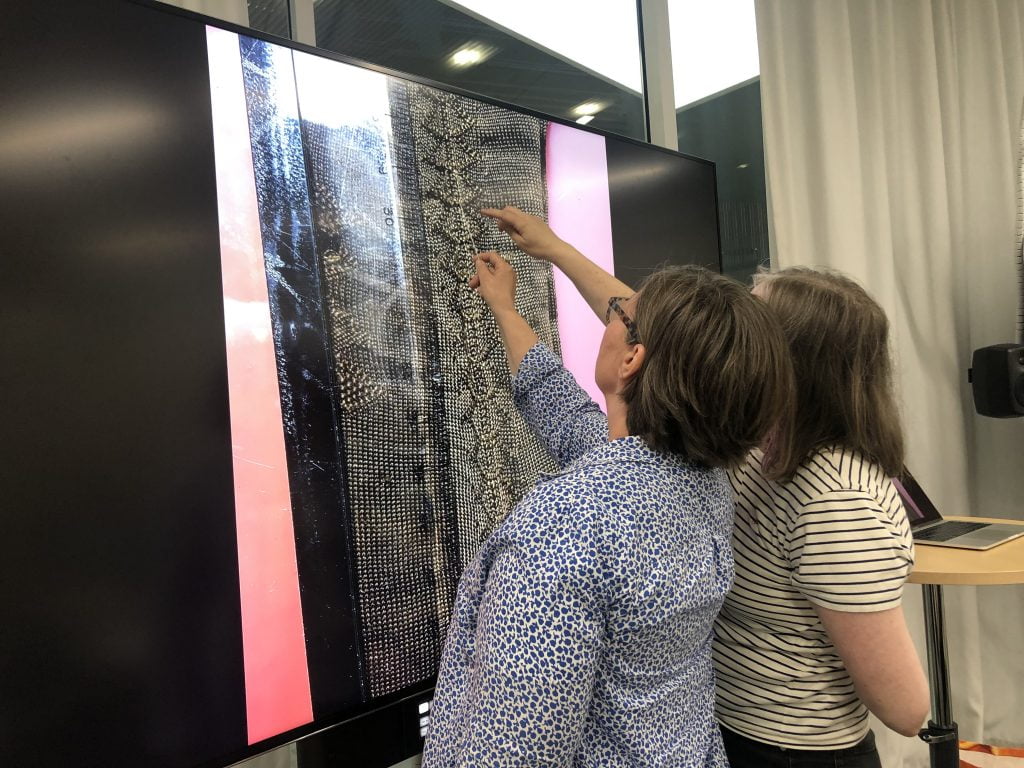

Another beneficial aspect of digital animation is the choice of illustrating material textures. Fabric surfaces in digital garments are actually photographic images of texture, inserted on top of the patterns. This means that it is relatively easy to change material textures and colours in digital animation. My early experiments with material texture show how different garments look depending on what kind of texture image is applied on top of the patterns. The appearance of a historical doublet is achieved with the right kind of texture image and colour. Figures 2-3 illustrate one of my first examples of the doublet and its texture. The doublet material is a photograph of a stamped velvet I made during the doublet tailoring course at the School of Historic Dress. Stamping was made by using a fork heated over a metal hotplate.

Figures 2-3. In one of the first doublet material experiments I used an image of a stamped velvet made by using a fork heated over a metal hotplate.

For the final digital reconstruction of the waterseller’s doublet, I chose to photograph the stamped mockado that was custom woven and dyed for the Refashioning the Renaissance project’s doublet experiment. I adjusted the thickness of the fabric first in Clo3D to resemble the thick, wool material. This also helped to refine the sculpted form of the doublet. The photograph of stamped mockado, however, appeared fairly dark in the digital environment even though it appears dark blue in the material reconstruction. Colour is easy to adjust in digital animation, consequently, I changed the blue tone slightly to make the stamped pattern more visible in the wool (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Refashioning the Renaissance digital animation experiment. Screenshot by Maarit Kalmakurki.

Because Francesco Ristori’s post-mortem inventory was one of the important starting points for the entire doublet experiment, I wanted to further use the benefits of digital animation and decided to make one version of the digital doublet in black (Figure 5). Black colour was difficult to achieve in the early modern period and very often dyed in hues of dark brown, red or green, depending on the dye recipe (see Ortega Saez and Cattersel 2022). The Refashioning doublet made at the School of Historical Dress was dyed in deep blue colour because expensive black was traditionally made by dying cloth with red and blue tones. Before the discovery of logwood, there was no dyestuff that made true black. In the case of the Refashioning doublet, the dyer made a very deep blue. Details, however, are difficult to perceive in any dark colours, so the stamping and ribbons almost disappeared in the black doublet. However, quite effortlessly, it helped us to achieve one of the goals in visualising what Francesco Ristori’s doublet might have looked like.

The method of implementing digital animation in dress history research proved useful in the Refashioning project. It offers new possibilities to test, experiment and illustrate historical garments, their construction, fit and materials. Alongside with hands on making, digital reconstruction helps to test textures and colours with just click of a mouse.

Image 5. Digital doublet reproduction in black colour. Screenshot by Maarit Kalmakurki.

See the full animation by Maarit Kalmakurki on our You-Tube Channel:

Digital Reconstruction of a Renaissance Doublet