Pharmaceutical Fashion: The Leather Tanner’s Jewellery Box

In The Treasury of Jewels (Venice, 1602, p. 228), Cleandro Arnobio explains that pearls represented many (and contradictory) things:

First, a thing prudently done.

Second, a holy thing.

Third, a thing much desired and a precious and expensive good.

Fourth, a vane and superfluous ornament that should be forbidden to women.

Fifth, an ornament on the gates of heaven

Queen Elizabeth I was well known for her love of pearls, which represented her status as a ruler and well as her great wealth, marine power and purity. Attributed to George Gower, Queen Elizabeth I (The Armada Portrait), c.1588. Oil on oak. Woburn Abbey & Gardens, Woburn, UK.

In fact, perceptions of gems and precious metals more broadly were complex and varied; these goods were beautiful works of nature that could be employed to honour the church, god and rulers but desire for them was also a huge, unnecessary expenditure for secular (and vane) adornment. In addition to glorifying and beautifying sacred and secular bodies, gems and semi-precious stones were also believed to protect and improve the health of those bodies. As Arnobio goes on to explain with respect to pearls, if ground into powder and ingested, they could cure ulcers, clear up sight problems, comfort the heart, staunch flux of the womb and taken with sugar, pearls could help cure pestilential fever (237). Pearls and gems were often ingredients in medieval and early modern medicines for a range of ailments and illnesses. The focus of this blog post, however, is on the health-giving benefits of wearing gems and jewels, like pearls, which were believed to temper the humours so that lust was reduced and chastity bolstered by those who wore them.

Drawer F with samples of materia medica collected by John Francis Vigani, Professor of Chemistry at Cambridge University in 1703-4, including shark’s teeth, pearls, sapphires, jacinth, lapis lazuli, garnets, rubies, topaz and other stones. Queen’s College, Cambridge University.

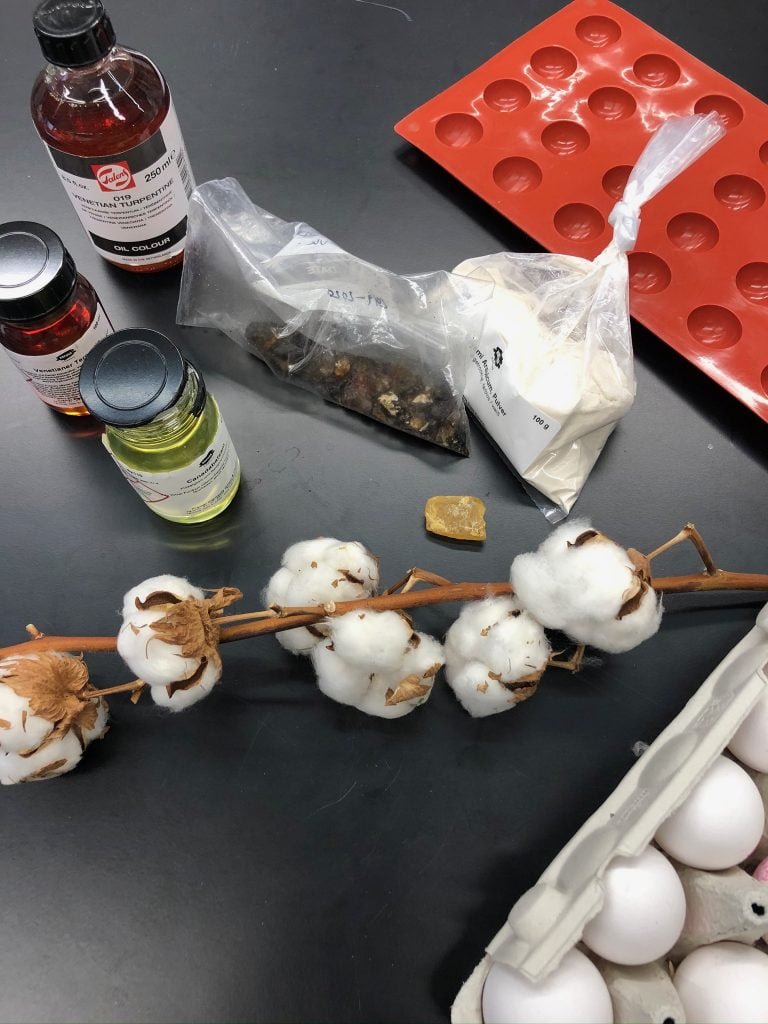

In particular, we’ll look at some of the jewellery owned by a Sienese leather-tanner, Pietro Paolo de Cheri as described in the inventory drawn up when he died in 1637. This list shows that he and his family members had access to necklaces, bracelets, rings, earrings, rosaries and hat badges that were made from or decorated with amber, jasper, coral, garnets, pearls and other precious materials. These were beautiful and sometimes costly goods that marked the economic and social status of the wearer as well as their age, marital state and religious and political affiliations, but they were also believed to have important health benefits that offered care and protection from harm and illnesses. Importantly, these kinds of objects and materials were just one way of supplementing other methods of protecting and defending individual and familial health, such as amulets, medicine, devotional practices and keeping one’s body, home and the air clean.

One lovely example in Pietro Paolo’s inventory is ‘a little amber rosary with fifteen silver buttons’. Rosaries were used by the faithful to keep track of their prayers, with beads of one size or material to mark the recitation of the Hail Mary, often punctuated at intervals of ten with a bead of a different material or larger in size, which signalled a different prayer was to be recited, usually the Our Father. In Pietro Paolo’s rosary, the amber beads marked the Hail Marys and the silver beads probably marked the Our Fathers, but these materials—amber in particular—were also important to prayer and maintaining good health.

Amber beads on a string of unidentified fibre, date unknown (medieval?). 65 x 114mm. Museum of London.

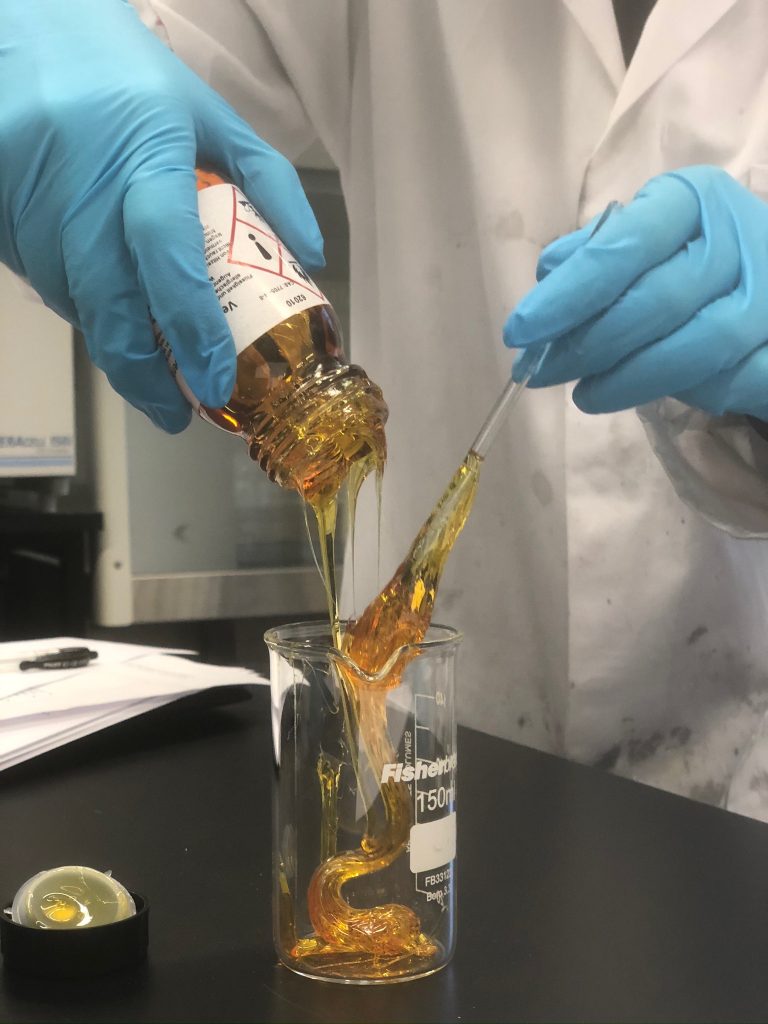

Amber – fossilized tree resin – largely came from the Baltic Sea in this period and was (and still is) valued for its beauty, rarity and its perceived powers. It can be shaped and polished, and was used for handles for cutlery, made into cups and amulets, featured in frames and also used in the form of beads, as with the leather-tanner’s rosary. It is especially suited to objects that are handled, as amber warms up through touch, and this warmth helps to release a scent into the air and the hands. This was important as part of religious practice and experience, but the smell produced was also believed to help purify the air and protect people against dangers like the plague, as Rachel King has shown. Amber was believed to be such a powerful prophylactic against illness (and a pleasant-smelling perfume), it was also ground and mixed with oil for perfuming gloves and pomanders, and was burned like incense to help clear the air of dangerous smells and spirits.

This pomander would be filled with scented materials like amber and musk pastes. Suspended from a belt, cleansing perfumes followed the wearer, wherever they went. Pomander, 17th century (Italian). Silver, 6.4 × 2.9 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Amber can also take on an electric charge when rubbed vigorously with another material, like wool. Sophie gave a demonstration of this—called the triboelectric effect—in our imitation workshop in March 2020, where a small piece of amber was ‘charged’ and then attracted small bits off of a table top like a magnet. This property was also recognised in the early modern period, leading some to recommend amber be used to draw dangerous substances out of the body. For example, the Belgian physician Johannes van Helmont (1577–1644) suggested rubbing amber on the wrists, temples, insteps and left breast to help prevent illness. As Martha Baldwin has argued, van Helmont believed that the amber, working like a magnet, would draw out from the body the dangerous odours that caused plague.

Pietro Paolo’s amber and silver rosary was not just an object that was beautiful and costly, but that supported religious practice by helping the devout count and keep track of their prayers. The feeling of the warmed amber beads and smell they released would add to the devotional experience, but also helped to purify the air of dangerous and even deadly smells and substances, helping to keep the believer safe and healthy.

Jasper was a material also praised for its beauty and usefulness in texts on minerals and gems, but unlike amber, it rarely appears in the inventories of artisans’ homes gathered for this project. Pietro Paolo, though, was one of the few people from our documents in possession of jasper, of which he had four pieces alongside some bits of coral. It’s not clear if these were just loose pieces, if they had been shaped, polished or treated in another way or what they were intended to be used for. The inventory also does not make clear what colour the jasper pieces were, as this opaque material could be found in a range of colours and combinations. Notably, the jasper does not seem to have been set in silver, the material recommended by contemporary writers for boosting jasper’s virtues, which include curing fever and dropsy (edema), allaying lust, encouraging conception, aiding childbirth, making the wearer virtuous and staunching bloody flux (dysentery). This was quite a useful and powerful material!

This intaglio shows just one type of jasper, which can range in colour and opacity. In the early modern period, the most highly esteemed was green jasper with red striations. Adoration of the Shepherds, ca. 1500 (Northern Italian). Jasper and silver, diameter: 51 mm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Much more common in artisan households and jewellery boxes were items featuring coral. In addition to the pieces that Pietro Paolo the leather-tanner had, he was also in possession of six coral necklaces: two featured coral beads and baroque pearls, three with just coral beads and one that combined coral, gold and stone beads. All the pieces except this last necklace are described as being ‘for girls’ and coral was believed to be particularly useful for keeping young people safe in this period. Early modern portraits of children sometimes show them wearing necklaces or bracelets of coral beads as well as coral branches, as it was believed the material would protect them from both witches and epilepsy. The Christ Child is also at times represented wearing coral beads and branches, and the material was, through its red colour, linked to the blood of Christ and redemption, giving it religious significance and power.

Here the Christ Child wears a necklace of coral beads and from which a branch of coral is suspended. Giorgio di Tomaso Schiavone, Madonna and Child with Angels, 1459-60. Oil on panel, 69 x 56.7 cm. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

This example of a Carved pieces of coral mounted in expensive enamelled gold were owned not by leather-tanners or other artisans, but wealthy and elite families (or the Christ Child). Carved coral amulet for a baby, mounted in enamelled gold filigree, possibly Italy, ca.1600. Height: 6.3 cm, Width: 2.7 cm, Depth: 2.2 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Adults, too, wore coral, especially women, as it was believed to help issues with menstruation, again due to its colour, as well as issues with the heart, stomach, intestines and gums. It was also believed that red coral would turn pale when touching the flesh of a person that had been poisoned, due to the vapours released through the pores of the skin. So, although a different result than with amber, physical touch was a key means by which coral could positively impact health.

An image of a young peasant woman from Chioggia, described as wearing a necklace of pretty coral beads in Cesare Vecellio’s costume book of 1590. Cesare Vecellio, De gli habiti antichi, e moderni di diverse parti del mondo libri due (Venice: Damian Zenaro, 1590), 150v.

Like coral, it was believed that carbuncles—red gemstones like garnets—would become pale if worn against the skin of a person who had ingested poison. Although not as common as pearls, coral or turquoise in the homes and jewellery boxes of artisans, garnets seem to have been fairly popular with this social group. They may have offered an affordable alternative to much more costly rubies, and there are twice the number of garnets versus rubies listed in the project’s inventories. There are also quite a lot of artisans with rings with ‘red stones’ that perhaps were intended to look like rubies or garnets; contemporary writers note that many tried to counterfeit carbuncles using glass pastes or coloured foils layered between pieces of rock crystal and the stone, which were hard to detect when set in rings.

Most often the garnets that appear in artisans’ inventories seem to have been worn in the form of beads strung alongside gold buttons, pearls and sometimes turquoise in necklaces and bracelets. This is the form the garnets in Pietro Paolo’s inventory took and he owned two necklaces of little garnets and gold beads. As these would likely rest against the skin, the garnet beads would, in theory, signal if the wearer had ingested poison. Additionally, this gemstone was believed to ‘gladden the heart and send away sadness’, and to ‘defend those who wore it against the plague’, as Ludovico Dolce described in his translation of a Latin lapidary into Italian in 1565 (26r).

In the inventories collected for the Refashioning the Renaissance project, garnets and pearls were often strung together in necklaces and bracelets; however, they also appear together as decorative elements in earrings and rings, as in this example. Enamelled gold fede ring, with a lozenge shaped bezel set with pearls surrounding an almandine garnet engraved with clasped hands, the back of the bezel engraved with a red flower, with later Roman mark for gold (1815-70), made in Italy c. 1640-60. Height: 2.8 cm, Width: 2.3 cm, Depth: 1.7 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

As I mentioned above, garnets in our inventories appear frequently strung alongside pearls, though this was not the case for Pietro Paolo’s collection of jewellery. Instead he owned a necklace of baroque pearls on two strings interspersed with black buttons, two pairs of necklaces of coral mixed with baroque pearls (mentioned above) and some earrings, bracelets and a medallion for a hat band all decorated with pearls. And it wasn’t just the leather-tanner, but many other artisans owned pieces of jewellery and accessories decorated with pearls; this gem can be found much more frequently than any other in the inventories gathered for this project. Like other precious materials, pearls were valued for their beauty, rarity and associations with purity. But they were also believed to have health benefits such as preventing fainting, problems with the heart and dysentery, as well as improving eye sight. Although the best way to benefit from pearls was to actually ingest them—pulverised seed pearls and other gems were a common ingredient in medieval and early modern electuaries—they also provided some health benefits when they were worn, as Cleandro Arnobio argued with respect to chastity.

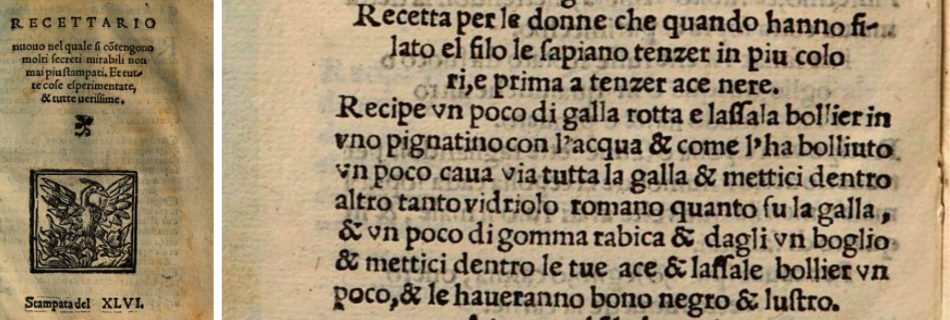

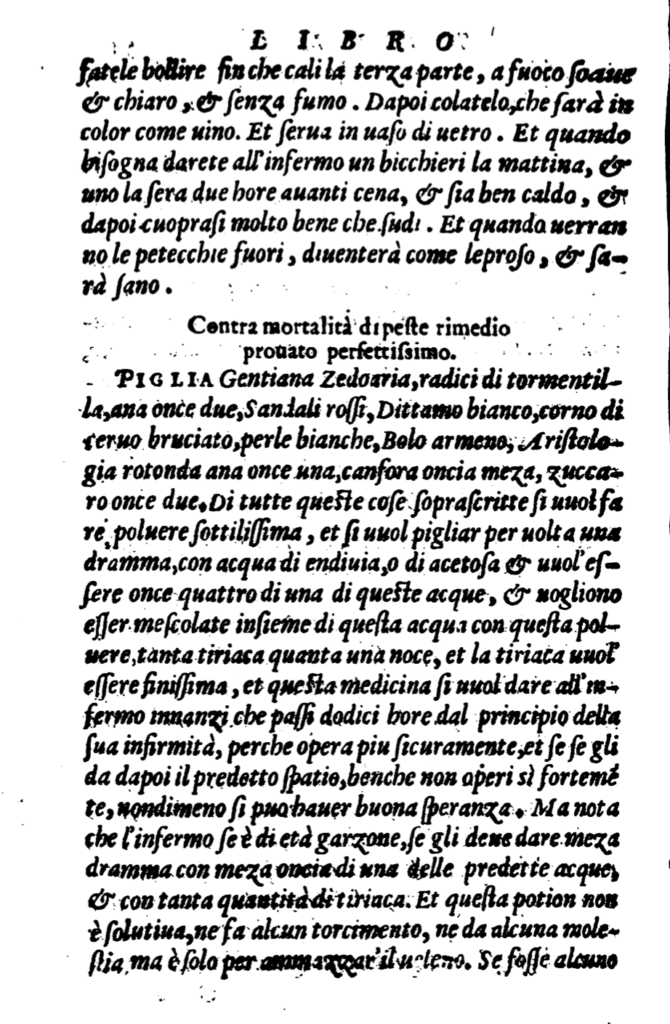

This recipe to prevent death from the plague calls for ‘white pearls’ to be mixed with other ingredients including deer antler, camphor and sugar; pearls and other gems were common ingredients in contemporary medicines for a variety of ailments. [Girolamo Ruscelli, De’ Secreti del reverendo donno Alessio Piemontese, prima parte…. (Venice, 1563), 51v.

One of my favourite descriptions of the prophylactic power of a gem is that for jacinth (also called hyacinth) given by Girolamo Cardano. He explains that, ‘it fends off the plague, which strikes mainly through fear and through weakness of the heart, and hyacinth abolishes both’ (369). Although the artisans studied as part of the Refashioning the Renaissance project did not own jewellery or accessories decorated with this reddish-orange gem, they often owned others that were believed to offer defence against a variety of dangers. Amber, jasper, coral, garnets, pearls and many other precious materials not discussed here provided wearers with not just a fashionable look, but together with clean linens, saying one’s prayers and sanitising the air perhaps offered some reassurance in times of illness. Although fear may not be the cause of illnesses, we know today it does negatively impact the immune system, so as a source of reassurance and hope, gems and jewels surely did support good health.

Ring with intaglio in jacinth showing the head of Minerva, seventeenth century. British Museum, London.

Works cited and recommended further reading:

The inventory of Pietro Paolo de Cheri’s homes and workshop can be found at the Archivio di Stato Siena, Curia del Placito, b. 280, f. 65, 1637, fol. 20v-26v; all of the jewellery is listed on fol. 23r.

Giovanni-Maria Bonardo, La minera del mondo, … divisa in 4 libri, (etc.) (Fabio Zoppjni, 1589), 22v and Lodovico Dolce, Libri tre ne i quali si tratta delle diverse sorti delle gemme che produce la Natura (etc.) (Venice: Gio. Battista Marchio Seisa, 1565).

Martha R. Baldwin, “Toads and Plague: Amulet Therapy in Seventeenth-Century Medicine,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 67, no. 2 (1993): 227–47.

Girolamo Cardano, The De Subtilitate of Girolamo Cardano, ed. and trans. J. M. Forrester, vol. I (Tempe, Ariz: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2013).

Sandra Cavallo and Tessa Storey, Healthy Living in Late Renaissance Italy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

John Cherry, “Healing through Faith: The Continuation of Medieval Attitudes to Jewellery into the Renaissance,” Renaissance Studies 15, no. 2 (2001): 154–71.

Maya Corry, Deborah Howard, and Mary Laven, eds., Madonnas and Miracles: The Holy Home in Renaissance Italy (London; New York: Philip Wilson Publishers, 2017).

Anselm De Boodt, Lapidary or, The History of Pretious Stones, trans. Thomas Nicols (Cambridge: Thomas Buck, 1652).

Lodovico Dolce, Libri tre ne i quali si tratta delle diverse sorti delle gemme che produce la Natura (etc.)(Venice: Gio. Battista Marchio Seisa, 1565), 45r. Giovanni-Maria Bonardo (conte), La minera del mondo, … divisa in 4 libri, (etc.) (Fabio Zoppjni, 1589).

Christopher J. Duffin, “The Gem Electuary,” Geological Society, London, Special Publications 375, no. 1 (2013): 81–111.

Marieke Hendriksen, “The Repudiation and Persistence of Lapidary Medicine in Eighteenth-Century Dutch Medicine and Pharmacy,” in Gems in the Early Modern World, ed. Michael Bycroft and Sven Dupré (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019), 197–220.

Rachel King, “‘The Beads with Which we Pray Are Made from It’: Devotional Ambers in Early Modern Italy”, inReligion and the Senses in Early Modern Europe, edited by Wietse de Boer and Christine Göttler (Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2013), 153–176.

Jacqueline Marie Musacchio, “Lambs, Coral, Teeth, and the Intimate Intersection of Religion and Magic in Renaissance Tuscany,” in Images, Relics, and Devotional Practices in Medieval and Renaissance Italy, ed. Sally J. Cornelison and Scott B. Montgomery (Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2006), 139–56.

James E. Shaw and Evelyn S. Welch, Making and Marketing Medicine in Renaissance Florence, (Amsterdam; New York: Rodopi, 2011).