Album Amicorum: Fashion, Friendship and Foreign Travel in Renaissance Europe

Michele Robinson

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, university students – especially those from Germany – often travelled to different institutions throughout Western Europe and documented their experiences in album amicorum, or friendship books. At first, these books were simply filled with mottoes and signatures from students’ friends and important people they met during their studies; overtime, though, the books featured inscriptions paired with images such as coats of arms, emblems and local people from the various cities visited. These images could be drawn by the person writing the inscription, painted by a local artist or taken from a printed book or single leaf, meaning that each album was as unique as its owner.[1]

Coat of arms and emblematic image with inscriptions from the autograph album of Johann Joachim Prack von Asch, 1587-1612. Getty Research Institute Collection, Los Angeles.

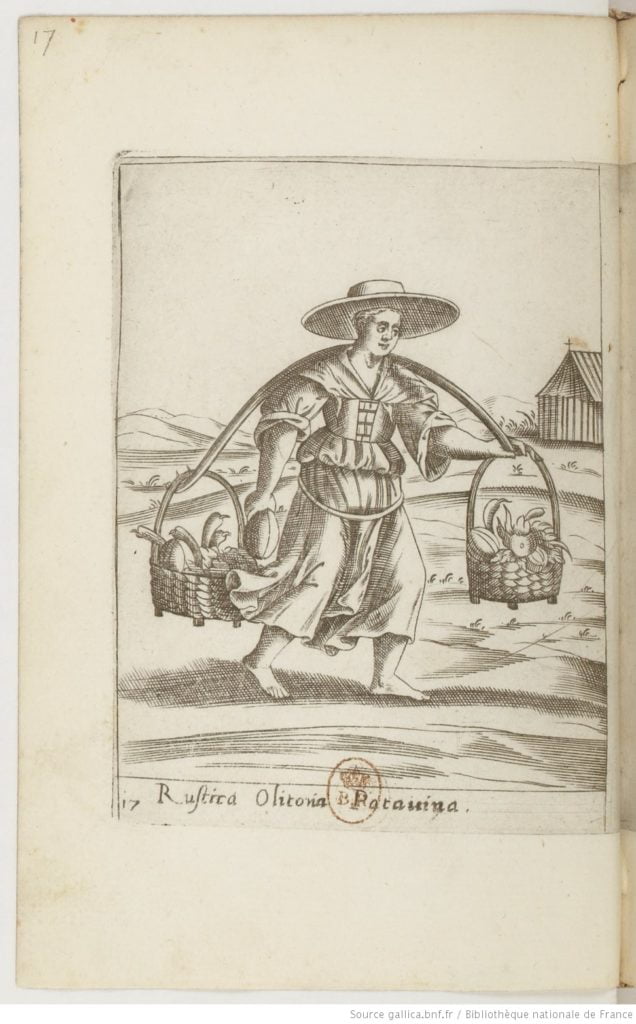

Along with revealing fascinating information about the experiences of German students, these books are also, perhaps surprisingly, useful for historians of dress. The representations of people included in the albums typically show men and women from different social classes wearing local dress. And, unlike most contemporary costume books, these representations are in colour, often still vibrant after more than 400 years, and the clothes are perhaps more up-to-date than in costume books, a sort of distant relative to the albums.[2] These books are useful for the Refashioning the Renaissance project not only because they represent dress, but often the dress – and scenes of daily life – of the lower-class inhabitants of Venice and the surrounding area. One of the most common ‘types’ of person from humble social origins depicted in the books is the female peasant from Padua, carrying two baskets of fruit, flowers or fowl over her shoulder.

Peasant woman (fol. 024r) from the Album Amicorum of Jan vander Deck, after 1592. Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS. Rawl. B. 21.

Peasant woman from Padua (fol. 032r), Album Amicorum of Paul van Dale, c.1569-1578. Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS. Douce d. 11.

Although these images come from different albums and neither is an exact replica of how such a woman would have looked or dressed, when we consider them closely and carefully, we can begin to reconstruct what a lower-class woman from Padua or other towns in the Veneto might wear. For instance, both images show the women with their skirts slightly puffed out around the waist, wearing quite long aprons and a garment draped around their shoulders and tucked into the front of their bodices.

Matrona Veneta [Venetian Matron], from Jan Baptist Zangrius, Album amicorum of habitibus mulierum omnium nationum Europae, tum tabulis ac cuneis vacuis in aes incisis adornantur, 1605. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie, Paris.

These kinds of representations also help to remind us that working people needed to have clothes that were practical and functional, though this does not preclude them from looking good. Unlike women from wealthy and elite families with floor-length (or longer!) gowns and towering platform shoes, working-class women had to be able to move themselves and perhaps their wares from place to place quickly and efficiently. The bunched-up skirts of Paduan peasant women may have created a distinctive look, but this was also a means of lifting the hem line away from the dust and dirt of the road on the way to market, and probably also prevented tripping on or ripping the garment. Thus, the images in album amicorum give us a sense of what people were wearing and encourages us to think about why they made these choices – both for fashion and function.

[1] For a general overview of the different types of albums and their chronology, see Max Rosenheim, “The Album Amicorum,” Archaeologia 62, no. 1 (1910): 251–308

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261340900008158.

[2] Margaret F. Rosenthal, “Fashion, Custom, and Culture in Two-Early Modern Illustrated Albums,” in Mores Italiae: Costumi e scene di vita del Rinascimento = Costume and Life in the Renaissance: Yale University, Beinecke Library, MS 457, ed. Maurizio Rippa Bonati and Valeria Finucci (Cittadella (Pd [i.e. Padova]): Biblos, 2007), 79–107.