Dirty Laundry in Aalto University

Can chanterelle mushrooms take the stains out of silk? Might elderberries dye yarn blue? Will scented rose petals make an artisan’s linens smell like those of a great lord? On the 11th and 12th of April 2019 the Refashioning the Renaissance team and two advisory board members explored these and other questions by recreating early modern recipes for cleaning and dyeing clothing and textiles.

Looking to the Danish and Italian contexts, we selected recipes that appear repeatedly in cheap and easy-to-obtain texts and pamphlets from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These texts were intended for use at home; they feature terse instructions and call for ingredients that were relatively easy for people to obtain, some of which may have even been growing in domestic gardens and pots. Some scholars have also suggested that many of the uncomplicated recipes found in printed and manuscript texts simply recorded folk practices that had long been carried out as part of everyday life.

Title page from Mangehaande artige Kunster at berede godt Blæk, Copenhagen 1578, the Danish text from which we took several recipes.]

Title page and image from Opera nvova intitolata dificio de ricette… (Venetia: Giovanantonio et fratelli da Sabbio, 1529). This is one of the texts we used in the workshop and is also one of the earliest printed recipe ‘pamphlets’.

Over two days, we followed instructions for removing stains, dyeing yarn and making scented sachets for linen chests to see if these popular recipes actually worked. On the first day, we had a brief introductory session, and then got to work in the dye kitchen at Aalto University.

Introducing the workshop and recipes.

Our first set of recipes were for stain removers, and Anne-Kristine and I spent some time the evening before staining the fabrics – many of which we had dyed during our visit to the Making and Knowing lab in New York in March. We used red and white wine, oak-gall ink and olive oil to stain the fabrics.

Michele and Anne-Kristine staining different fabrics the night before the workshop.

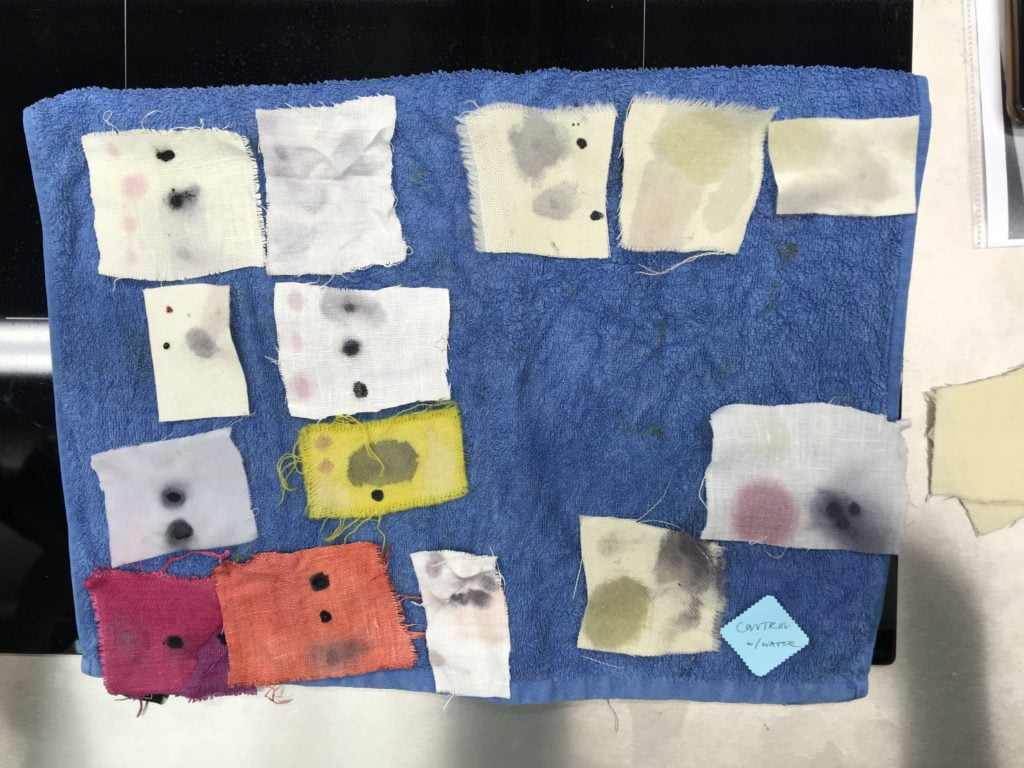

For the experiment, we split into three groups: Me and Sophie, Anne-Kristine and Tessa, and Paula and Flora. Luckily Piia was on hand to take lots of great photos and videos for us. Sophie and I prepared a very simple Italian recipe designed to take stains out of white wool or linen using lemon juice. We found that if we had fresh stains and blotted them before applying the lemon juice, our results with white wool were pretty good. On the set stains, though, the recipe was not so successful. We also noticed that the lemon juice really discoloured our linen dyed with cochineal, turning it hot pink.

Sophie with the cochineal fabric discoloured by lemon juice.

Michele and Sophie applying lemon juice to the stained fabrics.

The results of the lemon juice stain remover.

Anne-Kristine and Tessa recreated a recipe from a Danish text, using the juice of mushrooms to remove stains from silk. They decided to cook the mushrooms in a little bit of water, strain it and applied this to the stained fabrics. It didn’t work so well and actually discoloured the white silk. This might not be one to try at home!

Anne-Kristine and Tessa juicing mushrooms.

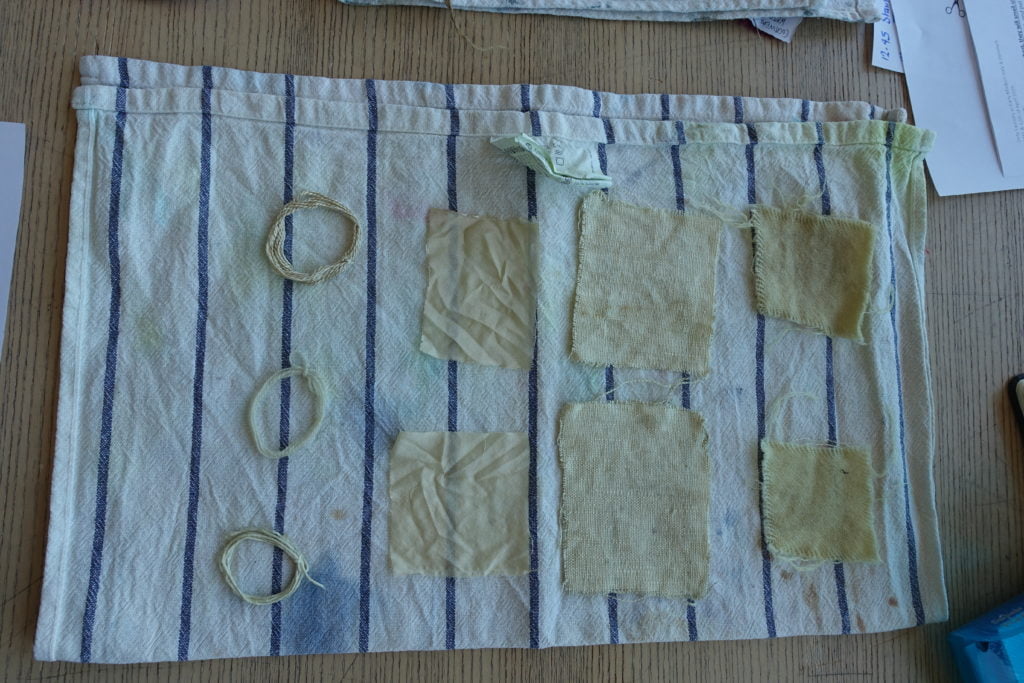

The results of the mushroom-juice stain remover, where you can see how it yellowed the white fabrics.

Finally, Paula and Flora recreated a recipe from an Italian book intended to remove stains from red silk using boiled cream of tartar. This was probably the recipe which was the least clear, and there were lots of discussions about whether to use the water or solid portion left after boiling. In the end, Paula and Flora decided to try both. Neither was particularly successful!

Freshly stained fabrics.

Preparing to strain the tartar powder.

Paula and Flora trying to remove stains from red fabrics.

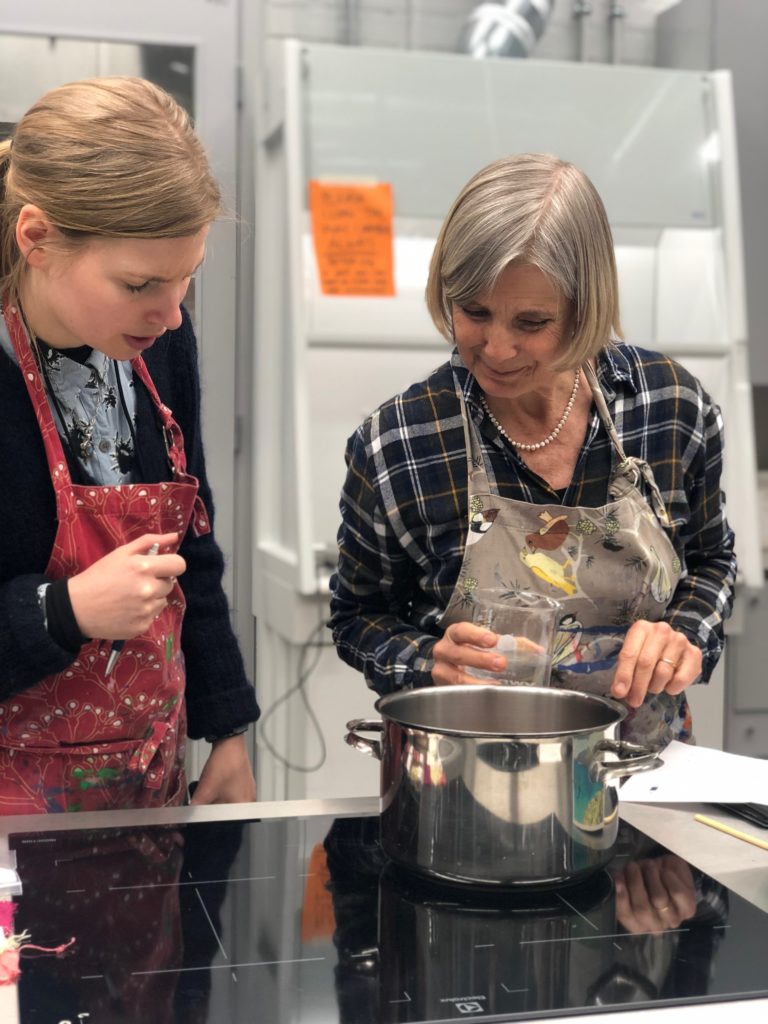

In the afternoon, we moved onto recipes for simple dyes. Anne-Kristine and I worked together, Paula and Tessa were a team and Sophie and Flora each worked on their own.

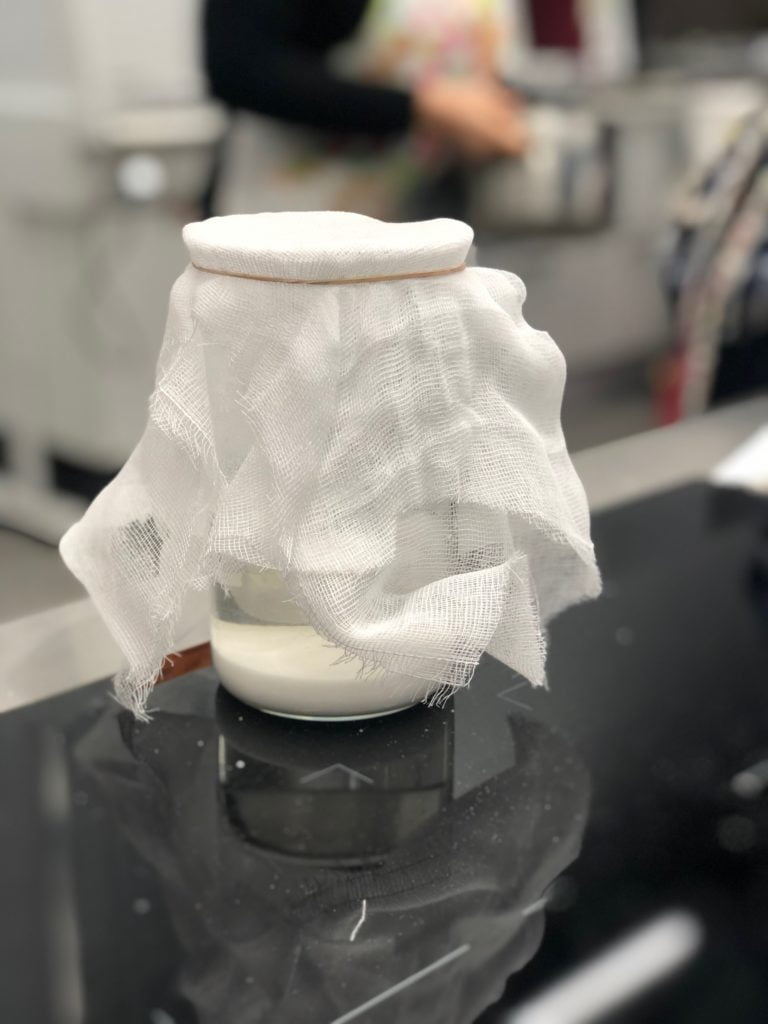

Anne-Kristine and I worked with a recipe from a Danish text, using bilberries to dye wool, silk and linen. A few days before the workshop I set the berries to soak in water (according to the recipe), and we just had to boil them a little, gave the mixture a strain and then added some alum and our fabrics.

Extracting the colour from bilberries, and fabrics added to the juice.

The results of our bilberry ‘blue’ dye.

The recipe was supposed to turn the fabrics blue, but they came out more of a deep purple-red. We were really happy and surprised about the results.

Sophie worked on alternative version of the same recipe, using dried elderberries, verdigris and alum. I had soaked the dried berries in vinegar for a few days before the workshop, and they smelled quite strong!

Sophie working with smelly, dried elderberries, which had been soaking in vinegar for several days.

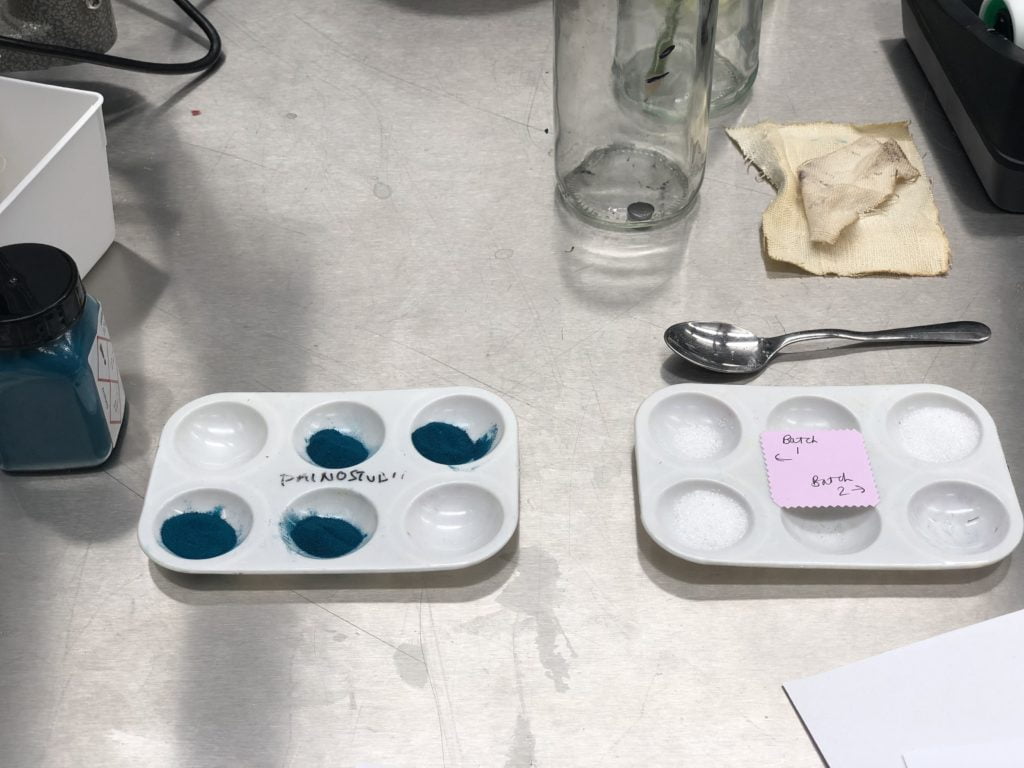

Two versions of the elderberry dye recipe.

Measures of verdigris (on the left) and alum (on the right) for Sophie’s two versions of the recipe. Verdigris is the lovely turquoise coloured patina that forms through the oxidation of copper or brass. Think of the colour of the Statue of Liberty!

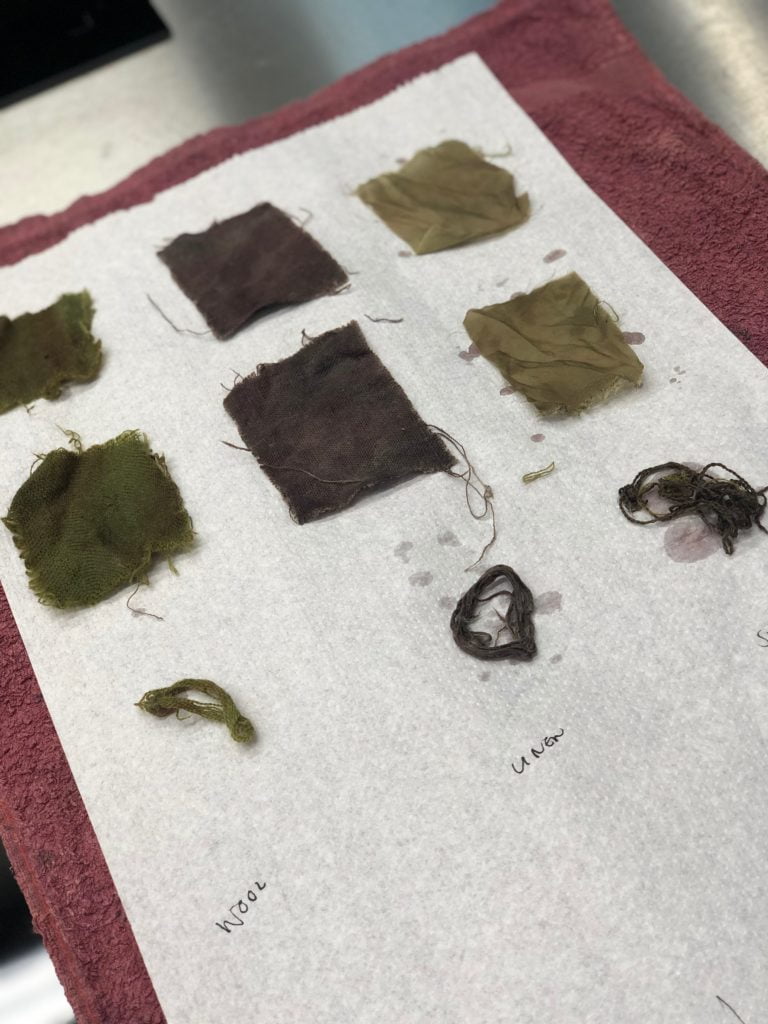

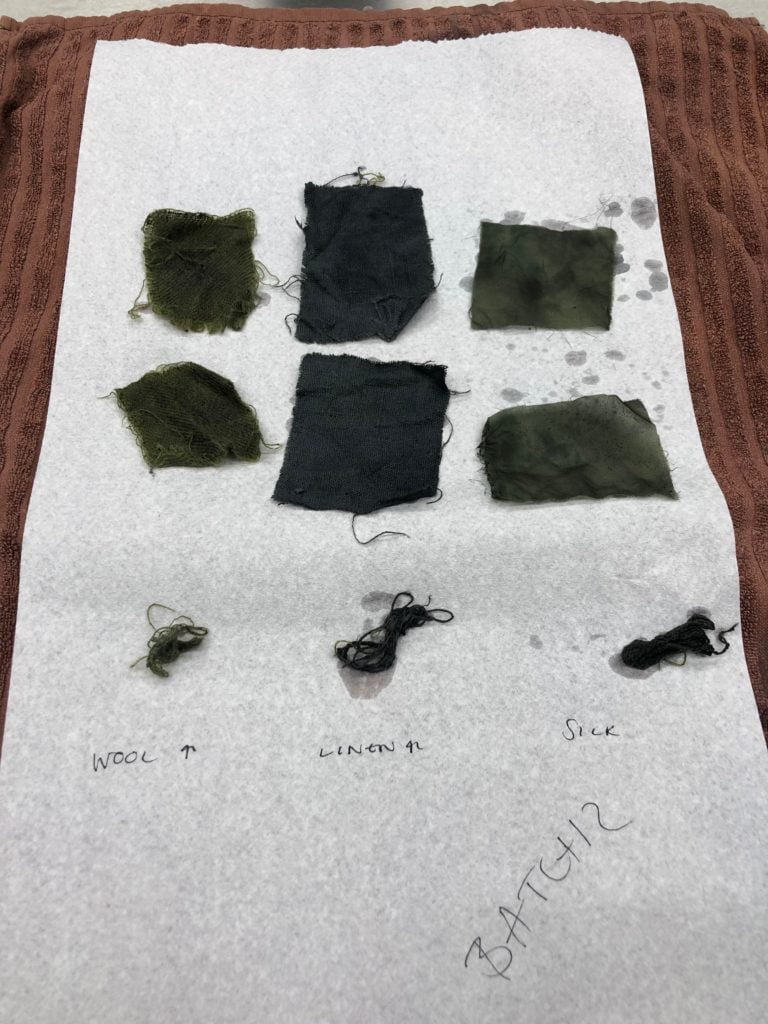

Her fabrics came out two slightly different shades of green, though the recipe was for achieving the colour blue…

Batch one of the elderberry-dyed fabrics.

Batch two of the elderberry-dyed fabrics.

Flora worked on an Italian recipe for making a russet colour. She used orange and pomegranate rinds that I had soaked in water a few days before the workshop. With the addition of alum and ash(!) she was supposed to end up with nicely coloured russet wool, silk and linen; however, the fabrics ended up a sort of creamy yellow.

‘Russet’-coloured fabrics?!

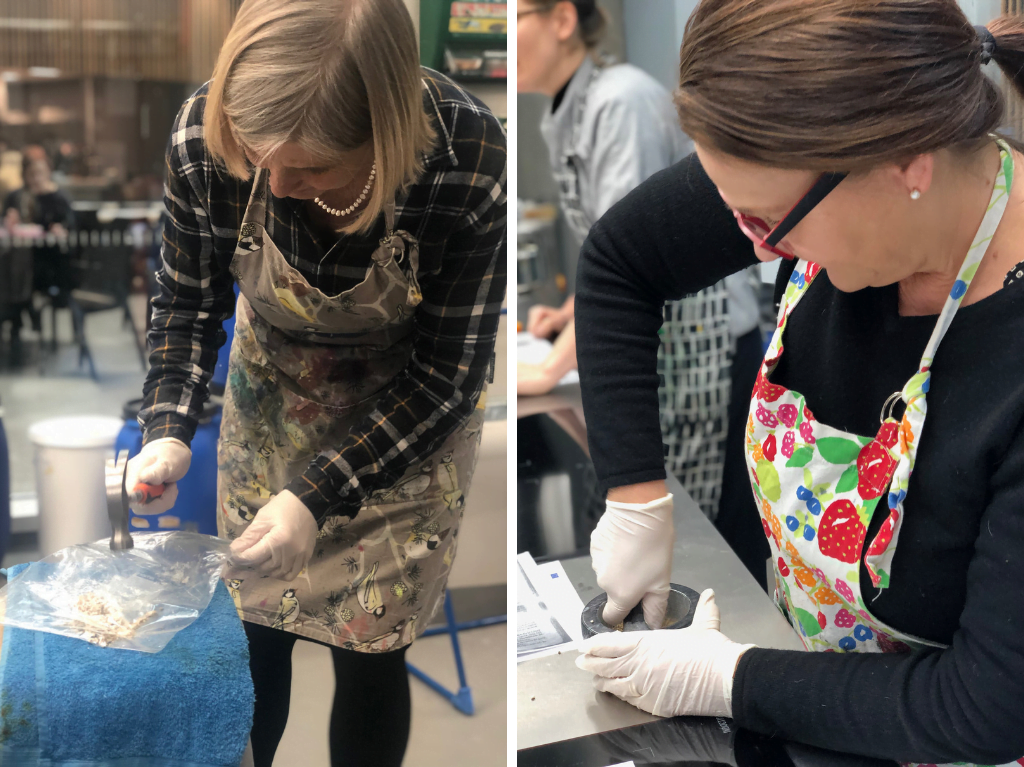

Paula and Tessa made a recipe from an Italian book, which also appears in many other books of secrets from this period. Their experiment was the most labour intensive, as they had to smash up oak-gall and grind gum arabic.

Tessa and Paula working hard, grinding and smashing.

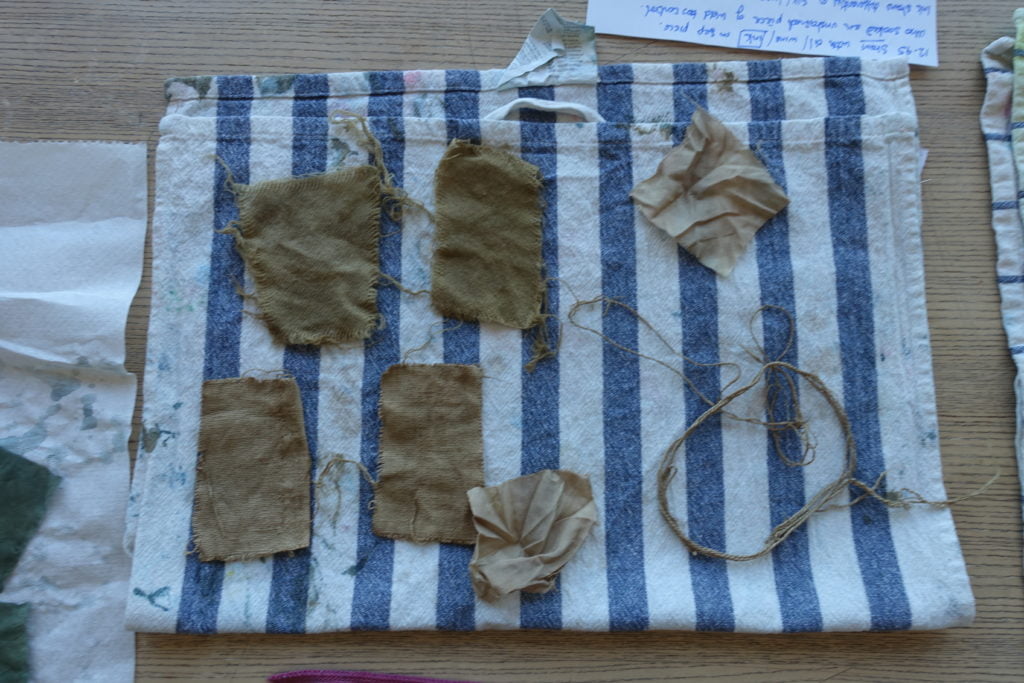

The recipe was supposed to result in a lustrous black; however, the team ended up with a muddy brown.

The dye is looking very mud-like.

Fabric that is ‘good, black and lustrous’?

Part of the problem—which we found for all of our dye recipes—was that the pots were much too large for the small amounts of textiles we were dyeing. This made the fabrics stick to the bottom and prevented us from swirling in the bath to get even coverage. Even though our stain removal and dye recipes were not so successful, we had many wonderful and useful discussions throughout the day.

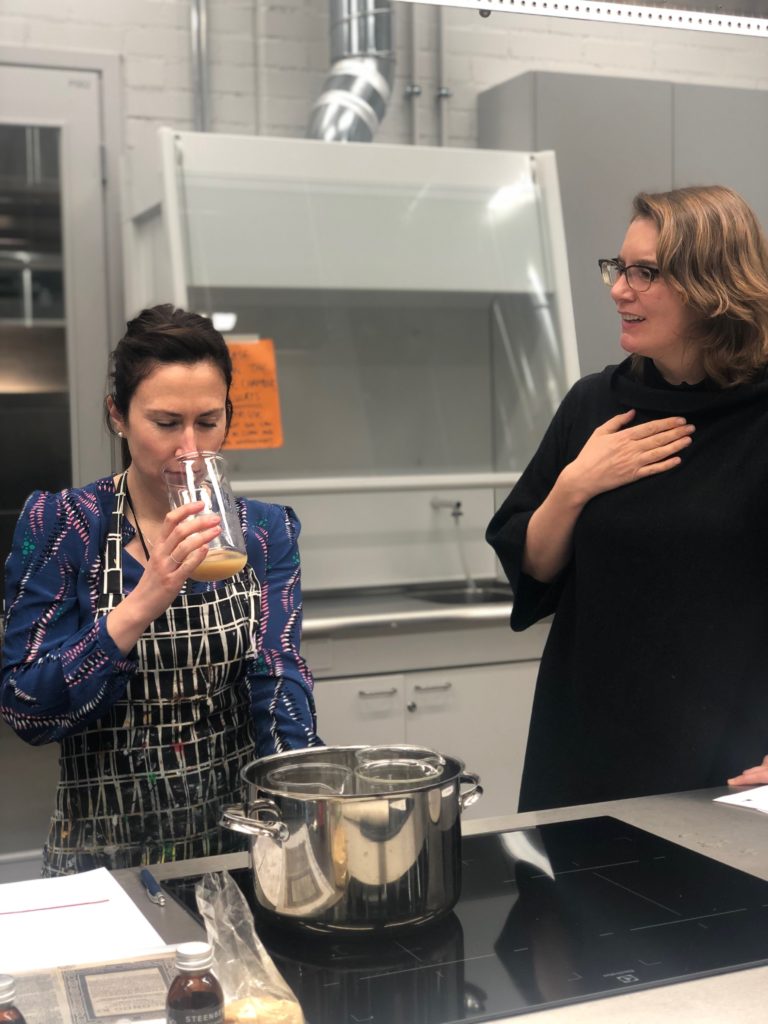

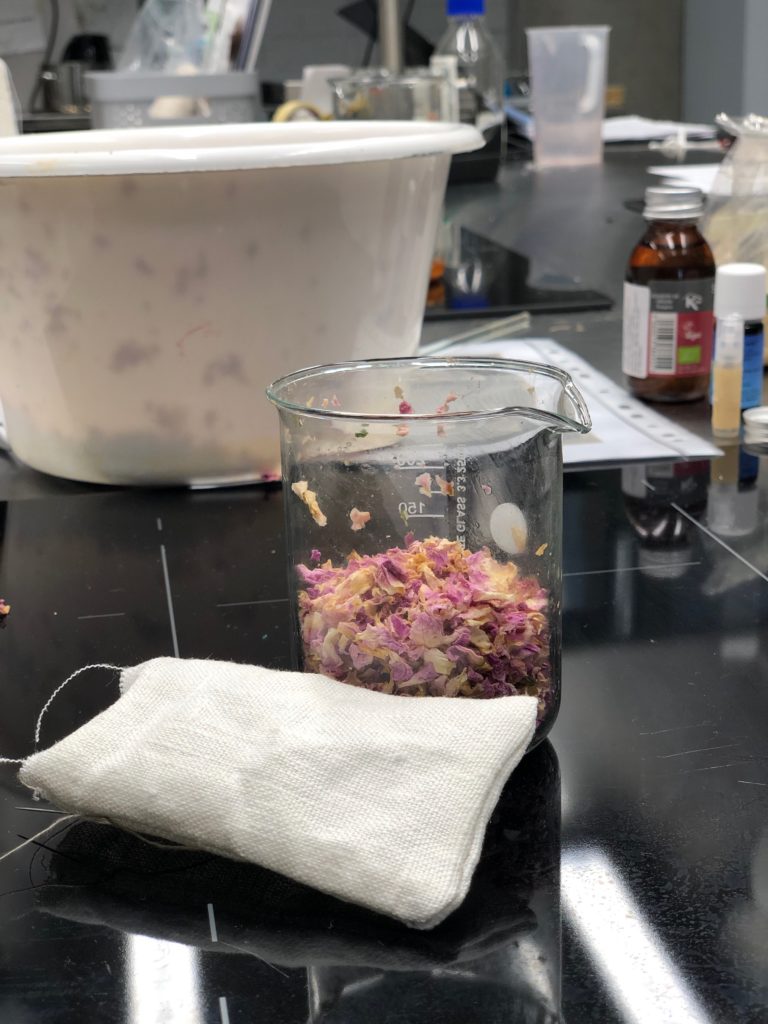

One the second day of the workshop, we recreated a recipe for making scented sachets for putting in linen chests. This was a very long recipe with two different options: one expensive, the other more economic. We chose the cheaper option, which required rose petals, rose water, musk [we used synthetic], lily oil and orris root. We shared the different tasks and had lots of discussion about the decisions we were making and why. It was a different atmosphere to the very busy first day in the dye kitchen, and we literally got to stop and smell the roses during this experiment.

Smelling the perfume to see if the odour is like that of a great lord, which we decided is an open question.

As our perfume cooked, we each sewed up linen bags. Once the mixture had cooled, we put it on the rose petals and added them, still damp, to our bags. The results were very fragrant and our office still smells of the mixture three months later!

Rose petals damp with the perfume, ready to be put inside the hand-sewn linen bag.

After we finished making up our bags, we gathered together to admire all we had produced during the workshop.

Wrap-up discussion.

We discussed how recreating the recipes helped us understand some of the practices that working people in early modern Italy and Denmark might have carried out at home to care for, clean or refashion their garments. Making these recipes also demanded close reading and that we considered carefully the kinds of knowledge and experience they assume the reader already possessed. It also gave us insight into the kinds of knowledge and experiences that regular people had, a topic that is hard to trace in this period given the low-levels of literacy, especially among women, who were unable to record their thoughts, feelings and actions. In sum, by recreating early modern recipes, we tested if they actually worked, and gained a broader perspective of and new questions about processes of and knowledge about cleaning and caring for clothing in this period.