Put a stamp on it: early modern embossed textiles

During the early modern period, people embraced decorative embellishments on clothing like never before. Glance at any portrait from the sixteenth or seventeenth century, and you will see clothing with a wide range of surface decorations ranging from elaborate geometric and floral patterns, large slashes and small pinks cut into fabrics, to applied ribbons, braid, pearls, gemstones and spangles.

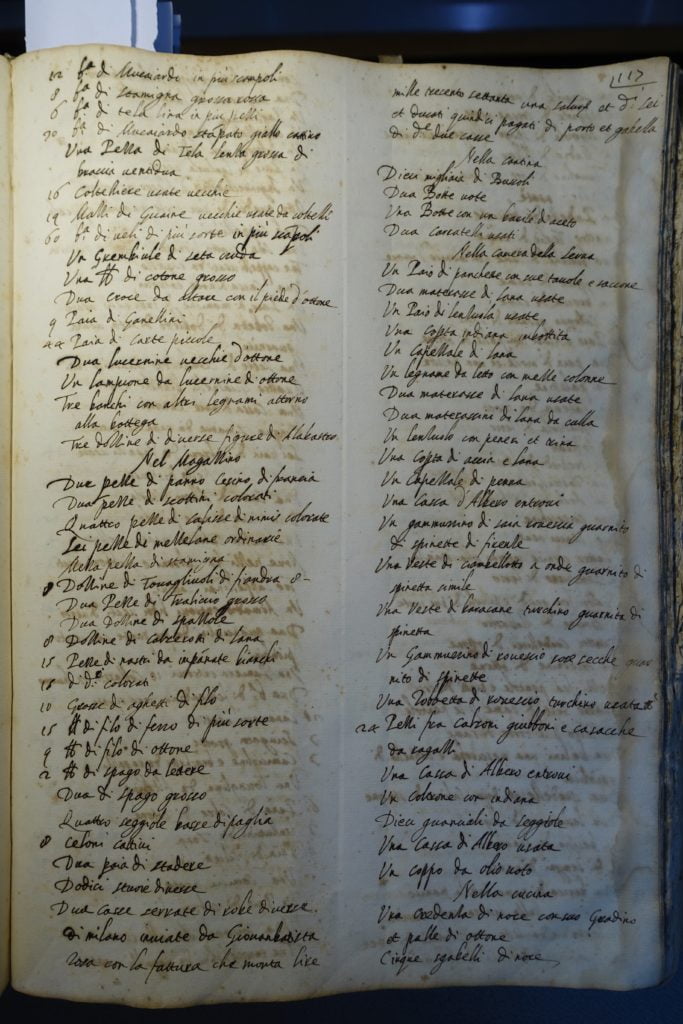

One method of fashionable surface decoration was stamping or ‘printing’ into textiles, embossing motifs into a fabric using heat and pressure. It seems to have been a technique embraced by the artisanal classes, for we find dozens of mentions of fabrics described as ‘stampato’ (stamped) in inventories from Florence, Siena, and Venice, particularly after the turn of the seventeenth century. For example, in 1627 the Florentine Linen merchant Filippo di Sforzo Guerrieri owned a pair of stamped sleeves and a white silk doublet that was both stamped and slashed, and furnished with gold ribbon (‘Un giubbone di raso bianco stampato et trinciato fornito con un nastrino d’oro’) (Archivio di Stato, Firenze, Magistrato dei pupilli, 2718/2, 13v, 1627). An inventory taken on 27 February 1634 recorded that the tailor Piero di Giovanni had 30 braccia of yellow stamped mockado in a nasty condition in his shop (‘30 braccia di mucaiardo stampato giallo cattivo’) (Archivio di Stato, Firenze, Magistrato dei pupilli, Folder 2719, 117r). Giovanni also owned a doublet stamped with waves (‘stampato a onde’).

One page of the inventory of Piero di Giovanni, 27 February 1634, Archivio di Stato, Firenze, Magistrato dei pupilli, Folder 2719, 117r

My current research on imitation textiles explores these stamped fabrics, which survive in relatively large numbers in museum collections. By the eighteenth- and nineteenth centuries, stamping became firmly associated with furnishing fabrics, so often these textiles are assumed to be fragments of wall hangings or furniture, but I am interested in finding out the uses of stamped textiles in clothing during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Extant textiles show a wide range of stamped designs ranging from the relatively small and simple floral motifs to large fleurs-de-lis and heraldic crests. Which designs were used for clothing, and what was the cultural importance of this method of design?

Fragment, 17th century, silk, Cooper Hewitt Museum, Gift of John Pierpont Morgan; 1902-1-462-a,b

One fabric that was often stamped to great effect was velvet, a fabric with a raised pile usually made of silk, but for those lower down the economic and social spectrum often made of mixed fibres such as wool, linen, or hair. Stamped patterns could imitate more costly methods of patterning, such as woven brocades or cut pile velvets, as in this example.

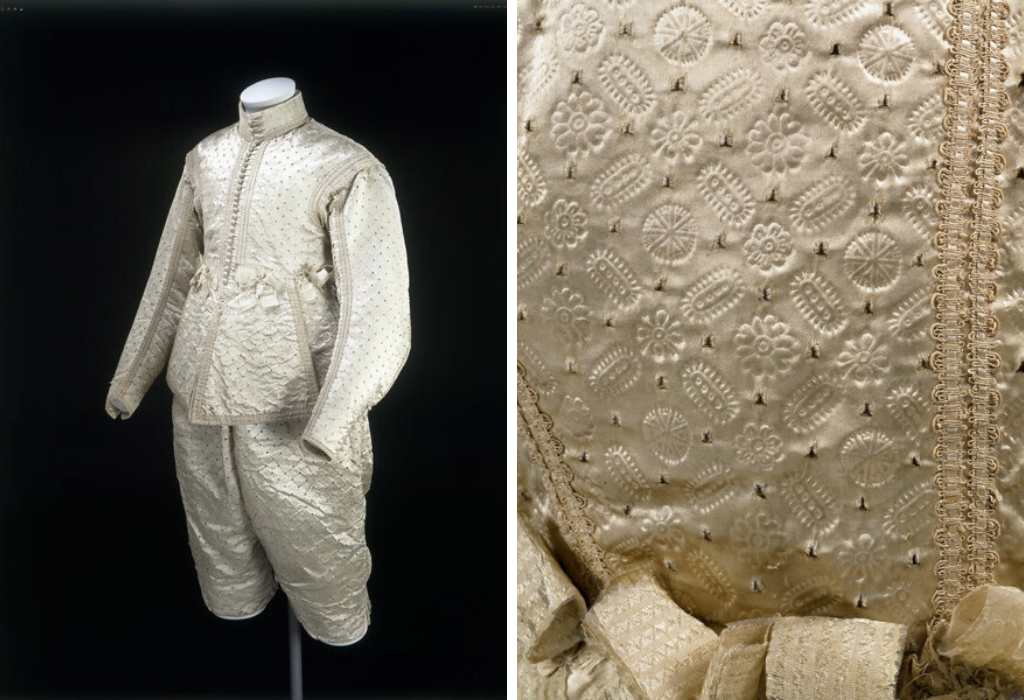

Doublet and Breeches, 1630-1640, satin, linen, and buckram, Victoria and Albert Museum, 348&A-1905 and a detail of the stamped satin.

But stamped fabrics were also enjoyed in their own right, as the method provided a means of changing the way light glances off the surface of the textile, as was likely the effect of Giovanni’s wavy doublet. The effect is strikingly different on soft wool, smooth silk, and plush velvets. A white stamped satin doublet and hose from the Victoria and Albert Museum gives us an idea as to what Filippo di Sforzo Guerrieri’s stamped silk doublet might have looked like, and shows that sometimes stamping was a technique not used to imitate woven or cut pile fabrics but instead was embraced for its ability to give texture to a shiny satin.

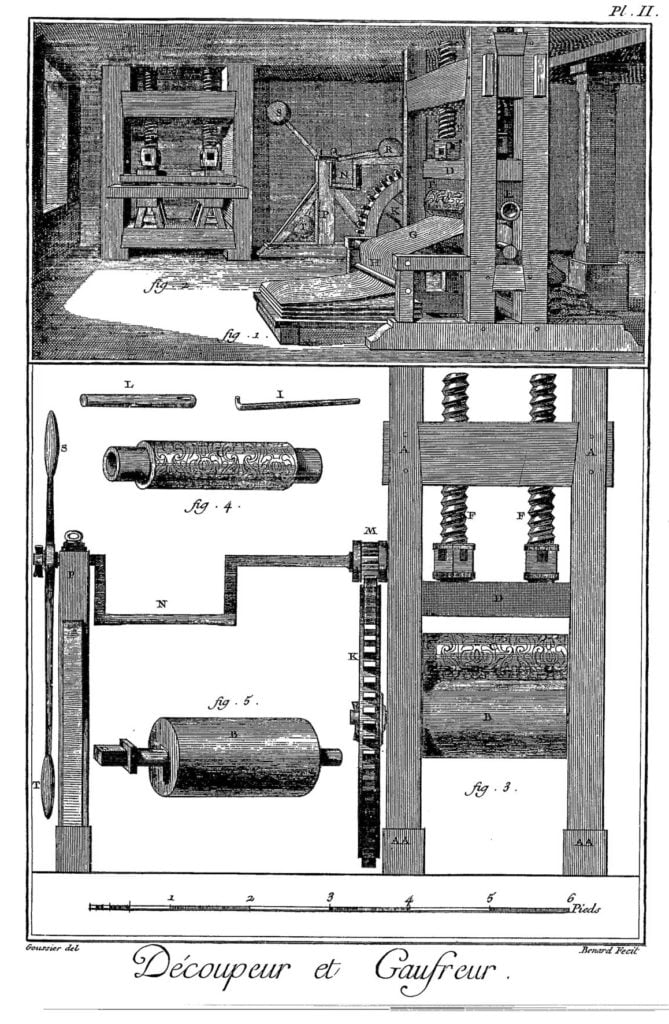

‘Découper et Gaufreur,’ in Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert, L’Encyclopédie. [38], Arts de l’habillement : [recueil de planches sur les sciences, les arts libéraux et les arts méchaniques, avec leur explication, (Paris, 1751-1780), Plate II.

In the eighteenth century, a rolling press to print or emboss pieces of stuffs, like velvet vests (‘pour gaufrer des morceaux d’étoffes, comme vestes de velours’) was included in Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (1751-1780). Detailed illustrations show how fabric is pressed between one plain roller and an engraved roller to imprint a repeating design across the upper surface of the textile. In earlier periods stamping was probably done by hand, using heated metal stamps. During a workshop at the School of Historical Dress in London, we experimented with stamping some velvet using the tines of a fork, heated over a hot plate. At first it was hard to calculate the correct amount of heat to create a clear imprint in the pile without burning the fibres, but once we had practiced a few times on offcuts of velvet we felt confident enough to stamp a hatched pattern quite successfully into our doublets.

Using a fork heated over a hot plate, we experimented with stamping a simple pattern onto velvet at the School of Historical Dress in August 2019. Photo by Sophie Pitman.

Explorations into these kinds of innovative, imitative, and inexpensive methods of decoration in clothing enable us to reconstruct the ways non-elite members of society were engaging with fashionable clothing in the early modern period. Our experiments with stamping will be published and put on display in due course, so check back on the Refashioning website for more information over the coming year.