Una corona di ambra falsa: Imitating Amber using Early Modern Recipes

To make cleere stones of Amber:

Seeth Turpentine in a pan leaded, with a little cotton, stirring it until it be as thick as paste, and then poure it into what you will, and set it in the sunne eight dayes, / and it will be cleaer and hard inough. You may make of this little balles, haftes for knives, and manie other things.[1]

Another:

Take the yelkes of sixteene egges, and beat them well with a spoone: then take two ounces of Arabicke, an ounce of the gumme of Cherrie Trees: make these gummes into a powder, and mire them with the yelkes of the egges, let the Gummes melt well, and poure them into a pot well leaded. This done, set them six daies in the sunne, and they will become hard, and shine like glasse, and when you rub them, they will take up a straw unto them, as other amber stones doe.[2]

These two recipes, taken from the 1595 English translation of Girolamo Ruscelli’s wildly popular Secrets of Alexis Piemontese, promise seemingly simple ways to make amber stones using turpentine and cotton, or eggs and gum. Part of the section of Secrets called “Divers waies for to die threed, yarne, or linen cloth, teaching how to make the dying of colours, and also to die bones and hornes, and to make them soft, unto what forme and fashion a man will,” this imitation amber is presented as a decorative and stylish stone, suitable for decorating knives or forming “little balls” presumably to set in jewellery.

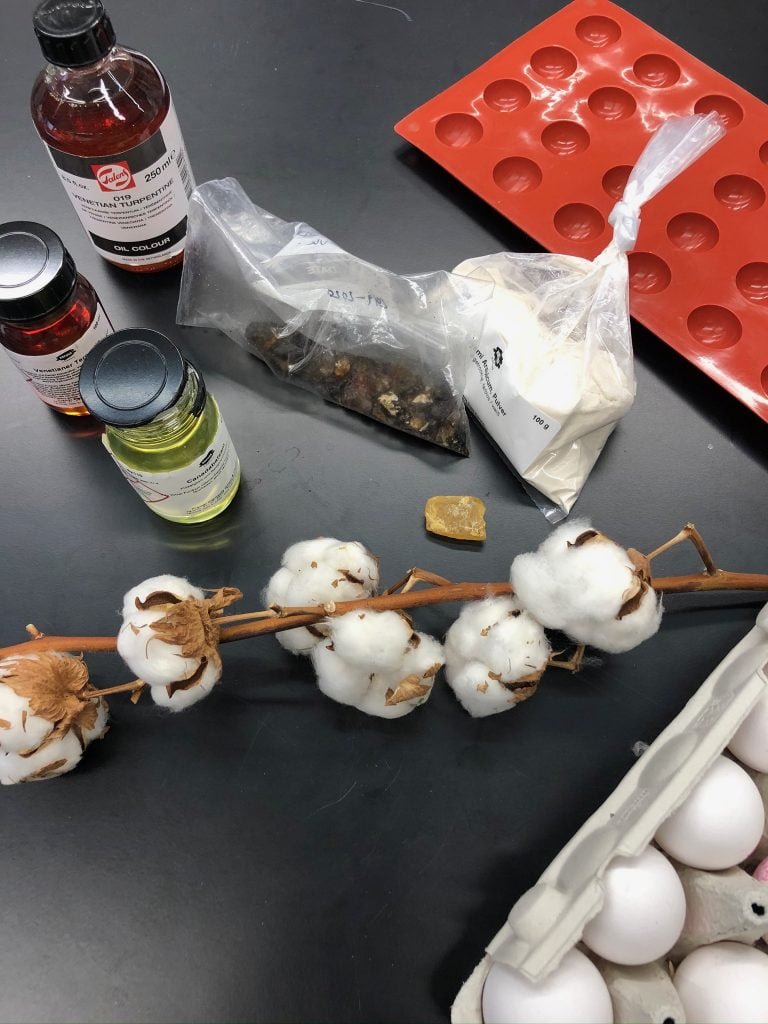

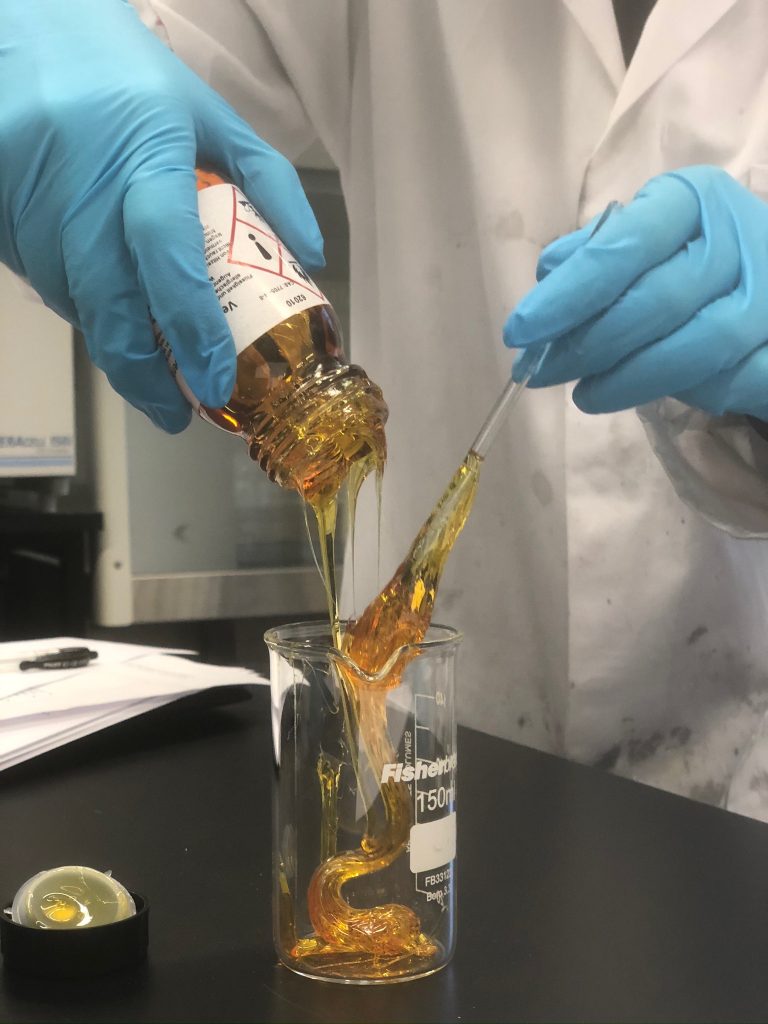

Last month, the Refashioning team tried out these two recipes as part of a workshop I organised about Imitations in Early Modern Fashion. Before we even began the workshop, my first challenge was sourcing historically appropriate materials. For example, what does Ruscelli mean by Turpentine? And where to find cherry tree gum? Through Instagram, I managed to find an artist who had collected some cherry tree gum last year in England, and was fortunate to be able to buy some from her. As for Turpentine, lengthy searches of scientific literature and many hours of watching YouTube tutorials about varnish making revealed that early modern turpentines came from a variety of trees, but were much thicker than our painting supply store distilled versions. I was able to source two different kinds of thick turpentines to experiment with: Venetian Turpentine, and Canada Balsam (which resembles the Strasbourg Fir Balsam used in early modern Europe, that is currently in low supply). More worryingly, turpentine has a very low flash point, and so heating it up is a dangerous challenge. We were lucky to be able to conduct our experiments in Aalto’s Biofilia lab, where we could carefully control the temperature and work in a fume hood.

The Refashioning Team and invited guest Timothy McCall, with James Evans (lab manager) at Aalto Biofilia.

The first recipe, using turpentine and cotton, was rather successful. The turpentine was incredibly sticky, and once we started to heat it up in the fume hood we were nervous about it igniting, but the smells were lovely, evoking a pine forest. The turpentines deepened in hue and became more viscous as they were heated, and the cotton seemed to provide some amber-like striations, as well as giving the gooey turpentine more structural integrity. The recipe suggests that once you have formed the mixture into balls that you leave it to dry in the sunshine for eight days, but in the absence of Italian sunshine in Helsinki, we left it indoors. Even two weeks later, the “amber” is a little sticky, but the colour and tone of both the Venetian Turpentine and the Canada Balsam is a convincing substitute for a piece of “true amber” purchased from a stone seller. The success of this recipe is perhaps unsurprising – “true amber” is fossilized resin, so the scent and appearance of heated turpentines would be very similar.

Can you spot the true amber? (Back left: Canada Balsam Imitation, Back Right: Venice Turpentine Imitation, Front: “True” Baltic Amber).

The second recipe, entitled “Another,” comes immediately after the first in Piemontese, but its results were very different. We decided to halve the recipe (sixteen eggs seemed excessive, and we wanted to conserve our limited cherry gum supply), but some of the instructions were hard to interpret – how were the gums supposed to “melt well” once already mixed with eggs? The eggs started to scramble in the heat, and we ended up making a sort of sticky cake. This raised more questions – Given that the first recipe specifies that the stones will be “cleere” was the recipe right to call for egg yolks instead of egg whites? Should we have melted the gums before mixing them into the egg, even though Ruscelli seems pretty explicit about the order? How is the egg supposed to set? The mixture looked very different to the first amber – it was not clear, but opaque and glossy with little spots of gum in it (which might have imitated a stone, but was certainly not clear amber). After a few days, this “amber” had gone mouldy, and had to be discarded.

Such outcomes prompt many new research questions about materials, process, and intended results. But this experiment, part of a series of hands-on investigations into imitation materials used in fashionable clothing and accessories in the early modern period, helped us to interrogate what it means to successfully imitate a material. Amber was valued in the early modern period for its smell, sheen, colour, and rarity, but intriguingly Ruscelli offers another means of testing the material in the second recipe. He notes that not only with these imitations be hard and “shiny like glasse,” but it will also be able to hold a charge: “when you rubbe them, they will take up a straw unto them, as other Amber stones doe.” Nowadays, scientists recognise this as the triboelectric effect, and even today experts still recommend that buyers of amber test that the stones are “real” by rubbing them and testing for a charge. Ruscelli’s suggestion shows that these kinds of material properties and responses were valued in an imitation as much as appearance. Any imitation stone that could mimic this effect would be a very successful piece of fake amber. It is important to note Ruscelli’s recipes do not suggest a binary opposition of “real” and “fake,” but compare the created stone to “other Amber stones,” so we must keep in mind that mimetic materials were not always considered inferior, and in fact could be highly valued for their artificially crafted properties.

Sophie Pitman demonstrates the triboelectric effect of amber, filmed by Piia Lempiäinen

Found in the Baltic regions then known as Prussia, and traded through Lübeck and Bruges, amber was a rare commodity in early modern Europe. As Rachel King has argued, amber objects in early modern Italy represented a “relationship to the north,” as to acquire amber in Southern Europe, you either needed to purchase it through well-connected mediators, or be given it by a generous gift-giver.[3] King suggests that amber beads arrived in Italy unstrung, and were then assembled into corone (rosaries), made into buttons, or attached to garments.[4] The Italian market for amber rosaries and other accessories grew from the mid-sixteenth century, probably because the Italian sumptuary laws lifted the complete ban on wearing amber in the 1490s. By the 1630s, people were hunting for amber in Italy, to apparent success in Sicily and Bologna (King suggests that most of these finds were not “true amber” and many coincided with archaeological excavations of ancient works), so given the popularity of the material and its relative scarcity in the region, it seems no surprise that Italians would have desired a way to create amber in the workshop such as the recipe offered by Ruscelli.[5]

Archival evidence suggests that amber, including “false” amber, was owned and worn by members of the artisan classes in the early modern period. The Refashioning the Renaissance Project database of over 600 artisan inventories from Florence, Siena, and Venice contains many mentions of amber, and one explicit mention of false amber. The 1646 inventory of Bernardino Ciampi, a cutlery-maker (coltalinaio) from Siena, records that he owned a rosary of fake amber with two crosses and silver medals (Una corona di ambra falsa con due crocette e medaglie di argento).[6] Given that he was a cutlery maker himself, perhaps he might have been inspired by Ruscelli’s suggestion to try making “ambra falsa” for knife handles, as well as for a rosary?

Knife and fork with carved amber handle in the form of a man, 17th Century, German, 16cm, Rijksmuseum, BK-NM-567&8.

Some of the artisans in the Refashioning the Renaissance database also owned amber objects that were real (or presumed real by those taking the inventories). A Sienese cap-maker owned amber paternoster beads as well as a rosary of amber and coral with a St Jacomo of amber (1 coroneta de ambra chani et corali cum un san Jacomo de ambro in un bosolo).[7] A butcher from Florence owned a black amber rosary with silver buttons or beads (1 corona di ambre nere tramezzato di bottoncini di argento, sette bottoni grandi di argento).[8] Giovanni Meulo, a tailor from Sienna, owned a pearl necklace with black amber buttons or beads (Una collanina di perle a postine con bottoncini di ambra nera). In Italian, the gemstone jet is referred to as “black amber” or ambra nera. Made from highly-pressurized and decomposed fossilized wood, jet’s Italian name etymologically connects it to amber. Such naming calls attention to the fact both stones come from trees (wood and resin).[9] Francesco Sala, a Venetian wool manufacturer, even owned gold and amber earrings.[10]

A strand of beads, possibly including amber stones. Detail from Petrus Christus (active by 1444-1475/6), A Goldsmith in his Shop, 1449, oil on oak panel, 100.1 x 85.8cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1975.1.110).

By examining archival sources alongside recipe books and surviving objects, and reconstructing processes of making “amber stones,” we can start to appreciate the fashionable materials of early modern Europe not just as commodities, but as stylish objects that evoked craft skill, international trade, and sensory experiences. Even on our first attempt at following the two recipes, we managed to create some successful amber-like stones with the first recipe, and with further trials might be able to understand how to interpret the second egg and gums recipe and create something equally successful. Imitations of fine materials like amber were not merely inferior or deceptive substitutions, but could be convincing alternatives that offered similar tactile and sensory experiences and visual effects.

[1] Girolamo Ruscelli, The secrets of Alexis: containing many excellent remedies against divers diseases, wounds, and other accidents, translated by William Ward, (London: 1595), part III, 251v-252r. The text was first translated in English from 1562-66.

[2] Ibid, 252r.

[3] Rachel King, “Whose Amber? Changing Notions of Amber’s Geographical Origin”, Gemeine Artefakte. Zur gemeinschaftsbildenden Funktion von Kunstwerken in den vormodernen Kulturräumen Ostmitteleuropas: Ostblick 2; 2014, v 1618- 8101

[4] Rachel King, in Christine Göttler and Wietse de Boer (eds). Religion and the Senses in Early Modern Europe. Intersections: Interdisciplinary Studies in Early Modern Culture. Leiden: Brill, 2013, 153-176.

[5] Rachel King, “Finding the Divine Falernian: Amber in Early Modern Italy,” V&A Online Journal, 5, 2013, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/journals/research-journal/issue-no.-5-2013/finding-the-divine-falernian-amber-in-early-modern-italy/

[6] 1646 Inventory of Bernardino Ciampi, Archivio di Stato, Siena, Curia del Placito, 283, 273, f.134v.

[7] 1551 Inventory of Antonia Baldigara r.ta Giovanni Marco q. Nicolò, a cap-maker. Archivio di Stato, Venezia, Cancelleria inferiore, Miscellanea, 38, 57, 3v, 4r

[8] 1570 Inventory of Della Casa, a butcher. Archivio di Stato, Firenze, Magistrato dei pupilli, 2709, fol. 19r.

[9] 1637 Inventory of Giovanni Meulo, a tailor. Archivio di Stato, Siena, Curia del Placito, 279, 29, fol. 115v. James Howell, Lexicon Tetraglotton: An English-French-Italian-Spanish Dictionary (London, 1660), 330v. Thanks to Katherine Tycz for this reference.

[10] 1640 Inventory of Francesco Sala, a wool manufacturer. Archivio di Stato, Giudice di Petizion, Inventari, 357, 24, Venezia, fol. 8v