Sampling tailor’s techniques—launching the experimental phase

What skills did artisans use to achieve Renaissance fashions? How can historians learn and study with their hands? These questions are on our minds as we launch the experimental phase of the Refashioning the Renaissance Project. For our first foray into hands-on making as a team we decided to get to grips with tailoring, and so we invited Melanie Braun, Head of Wardrobe at the Nationale Reisopera, Enschende, Netherlands and teacher at the School of Historical Dress, London to Aalto University to lead an intensive two-day workshop introducing us to early modern tailoring techniques.

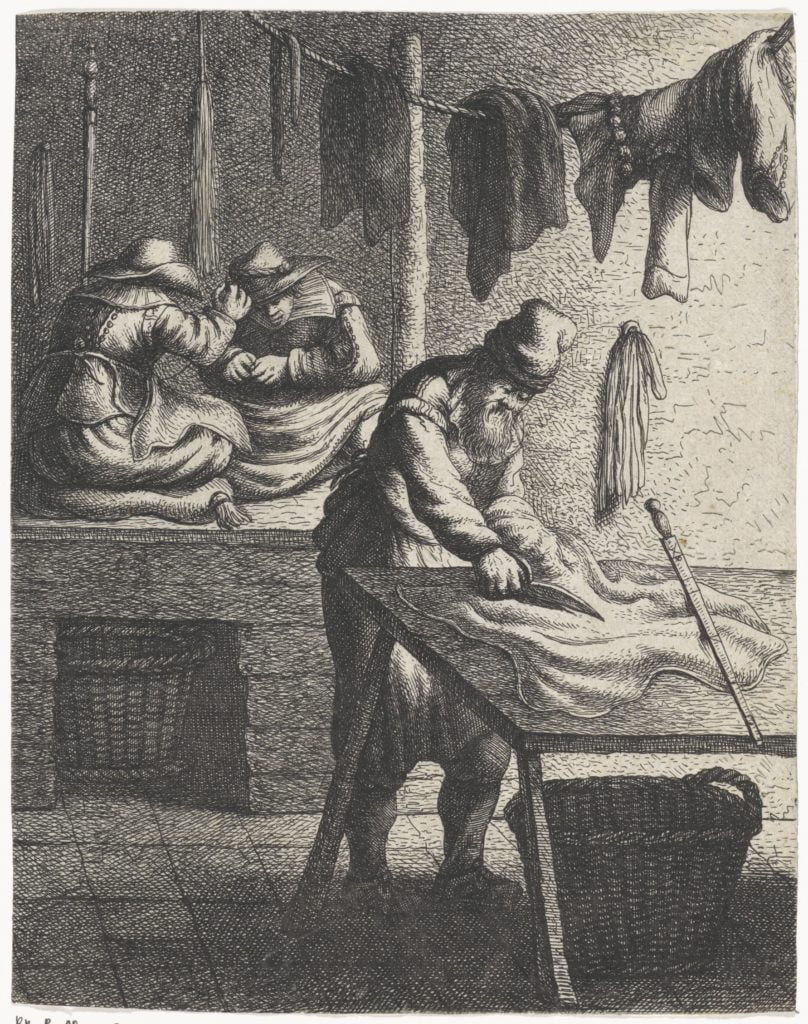

Jan Georg van Vliet, Kleermaker, 1635, etching on paper, 21 cm x 16.2 cm, Rijksmuseum RP-P-OB-103.713

Melanie is a trained tailor whose skills were honed during an apprenticeship at the Staatstheater Braunschweig, and many years working in theatre companies, including at Shakespeare’s Globe. Along with the rest of the team at the School of Historical Dress, she has closely examined dozens of surviving early modern objects in museum collections and has created patterns and reconstructions of many sixteenth- and seventeenth-century garments. Our workshop focused on both the range of stitches and materials used by the tailor, and the geometrical pattern drafting that enabled the creation of the distinctive shapes of renaissance clothing.

Melanie Braun holds up a sampler showing early modern tailoring techniques.

We set out to create a small sampler which enabled us to try out the types of stitches, linings and techniques that tailors used. First we began with running stitch, a stabbing in and out action that many of us were familiar with from school needlework lessons. But once we started exploring a range of possible stitches – back stitch, half-back stitch, felling stitch – we realised how these techniques required different amounts of thread, took varied amounts of time and concentration, and provided a range of strengths and visual effects.

Sophie Pitman concentrates on making an even stitch.

Even seemingly simple tasks, like repeatedly threading a small needle or being able to create a balanced and neat stitch could be challenging to us as amateurs. Seeing how quickly Melanie could create a knot with one hand or judge just the right amount of thread to use, demonstrated the value of years of experience, something that twenty-first-century and sixteenth-century tailors alike acquire over years of apprenticeship.

Melanie showing Michele Robinson how to work with a thimble.

Using wool and short staple unspun cotton, we experimented with quilting, which tailors often sewed into the linings of a garment to provide shape, warmth and even protection. Structure could also be added with pad stitches, diagonal stitches done in v-shaped rows that give collars, bellypieces, tabs and shoulders added volume and curves. Tailors also sat on the table in order to use their bodies to shape the fabric.

Piia Lempiänen works sitting on the table, just as tailors did in the seventeenth century.

We also tried drafting pattern shapes with a compass. While we do not know exactly how tailors measured their clients and then drafted patterns for them which ensured a flattering and fashionable fit, a close examination of surviving garments suggests that early modern tailors were true geometers, using proportion and curves to create elegant and balanced shapes. Watching Melanie expertly draft a pattern, combining her trained eye for shape and her knowledge of well-proportioned measurements, demonstrated how the tailor had to know mathematically and practically how to transform two-dimensional materials into three-dimensions.

Geometrical pattern drafting of a doublet front.

Hands-on experimentation revealed how actually trying the various steps in the making process can raise many questions about early modern material culture – how, for example, did tailors measure their clients, where did they source their lining materials, how strong were the smallest needles in the sixteenth century, and did tailors feel anxious when cutting valuable materials? Working with skilled makers helps us to ask better questions and fill in gaps where no archival, visual, or material records survive, and it also helps us better understand extant sources. By working with our hands, we are also training our eyes. When looking closely at garments in museums that contain some of the techniques we struggled with, we can better appreciate the tailor’s highly skilled work.

Not only did these two days enable us to experience some of the techniques used by skilled artisans, but the workshop was also an opportunity for us to learn how best to document our experiments with field notes, photographs, and films. Over the coming months, we will continue to share our experiences with hands-on experimentation.

Further Reading:

Janet Arnold, Patterns of Fashion 3: The cut and construction of clothes for men and women c. 1560-1620, Macmillan, 1985.

Melanie Braun, Luca Costigliolo, Susan North, Claire Thornton & Jenny Tiramani, 17th Century Men’s Dress Patterns 1600–1630, Thames & Hudson & V&A, 2016.