On the 9–20 June I attended the summer school Museum Objects as Evidence: Approaches to the Material World in Amsterdam. The summer school was arranged by the Rijksmuseum, University of Amsterdam and the Bard Graduate Center.

My initial motivation for applying the program was to become more familiar with the methods in analyzing historic objects, and get inspiration on how to include and work with cultural heritage objects in my own PhD dissertation. Next year I am going to look more into the archaeological and material evidence of the dress of the lower levels of Denmark. I felt that I needed tools to approach this topic as a historian, since we are generally not used to work with objects in the material sense.

During the two weeks I got strong insight on how to use cultural heritage objects as sources of information. Some of the overall topics that were considered were damage or decay, object as evidence, reading the object, issues of authenticity,meaning through display, reimagining the object, the biography of objects, interdisciplinary research, and how we think of objects in the future.

Every day we were presented with a new topic and specialists showing us their work with groups of objects from the Rijksmuseum collections, ranging from Delft pottery to fine art paintings, and photography to colonial artefacts, metal wares and textiles.

Some of the sessions I found particular interesting, such as a session about metal objects and metal thread. Here we were presented to some of the treasures from a Dutch shipwreck, including items such as a powder box and a toiletry set containing many items, for example a mirror covered in velvet, and metal threads.

Some of the metal items from the shipwreck. The mirror from the toiletry set can be seen in the background. Photo credit: Anne-Kristine Sindvald Larsen.

In another session that I was very intrigued by, we were presented a highly decorative table ornament, which was decorated with small life casts of small fauna and flora. In effort to understand how the object was made, and to comprehend the highly complicated processes that artisans were able to perform almost 500 years ago, conservators had used contemporary recipe books to help them gain knowledge of the process of making life casts.

Wenzel Jamnitzer, tablestand (1549). Photo credit: Riijksmuseum.

Details of life casts of snakes and lizards. Photo credit: Riijksmuseum.

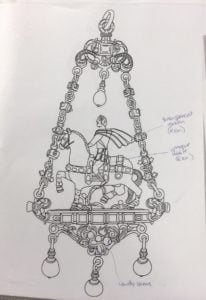

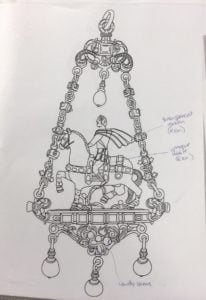

I was also very lucky to try out some technical examination methods on a piece of Renaissance jewelry. By using different technical approaches, we were able to determine the color pigments in the enamel, the quality of gemstones and pearls, and possible alterations and repairs. This made us understand the history of the object and what it had gone through in detail, and also led to quite a surprise. Turned out that the piece of jewelry that at first seemed to be an authentic renaissance object, had a frame added to it in a later period. This shows how important it is to take a deep and critical look into the history of the object, and interpret all the traces the object has to reveal about itself.

A Renaissance pendant is being examined. Photo credit: Thijs Gerbrandy.

The worksheet from the piece that were examined at the workshop.

Even more interesting, we also had a session on textiles, where 17-century bridal gloves were laid out for examination and where we were able to really see the cut and construction of the gloves, and get a closeup of the elaborate decoration, materials, and stitching.

A pair of bridal gloves that we were lucky to get a closer look at. Photo credit: Rijjksmuseum.

Every afternoon the day ended with a discussion where two students were in charge of presenting the main points of the day and their thoughts about the topic in general and in relation to their own project. This led to some very interesting discussion and inspiring thoughts.

What I also learned during these two weeks, is how important interdisciplinary views and approaches are when working with objects. Besides the strong academic focus during the summer school, I got a chance to network and meet other researchers and museum professionals all interested in working and engaging with material culture in different ways.

Group photograph in the Rijksmuseum garden. Photocredit: Thijs Gerbrandy.

Before attending the summer school, one thing that I was especially interested in was to get an idea of how to cope with anonymous objects without any context or known provenance, since this is mostly the case with the archeological remains that are left of ordinary people’s dress in Denmark.

After these two weeks I feel more confident in working and incorporating objects in my own work, I have a stronger sense of what questions are relevant to ask, and know that even simple results can lead to a greater understanding of the objects and thereby the society it was made in. I also know more about the possibilities in terms of methods and approaches, and more importantly I have gotten a sense of how objects can transform our understanding of the past, but also how our understanding of objects keeps changing though time.

I look forward to using this knowledge in practice in the future.