Research Trip to Milan, May 2018

Michele Robinson

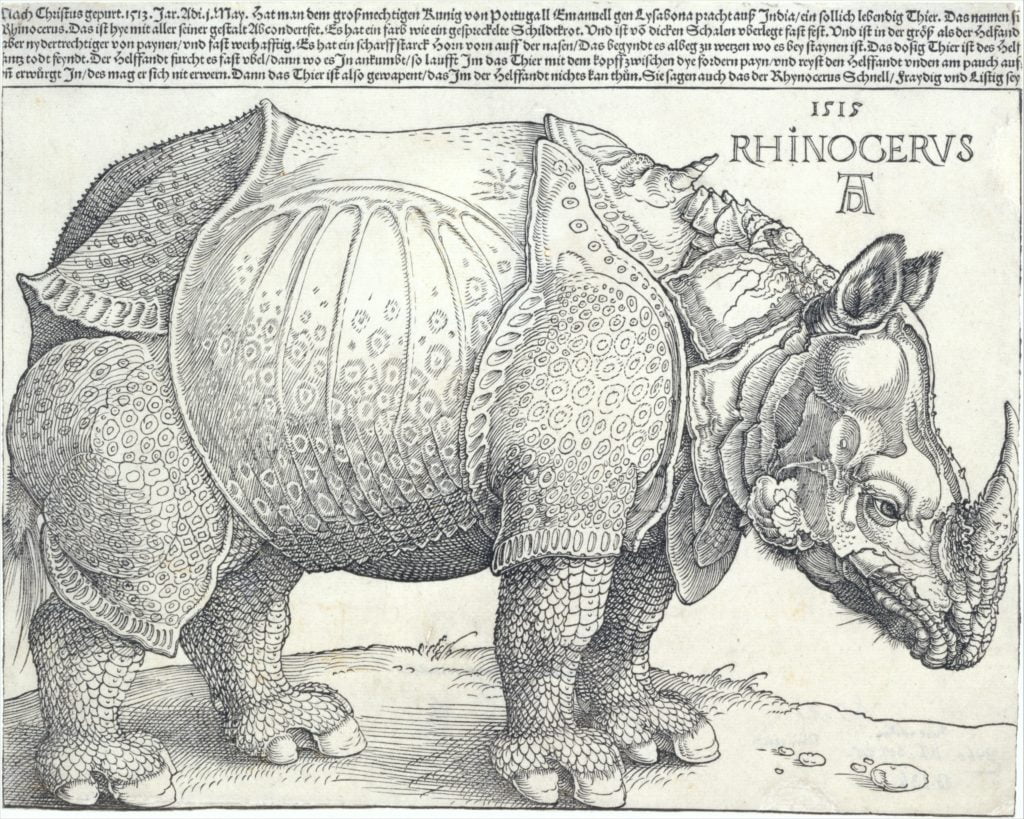

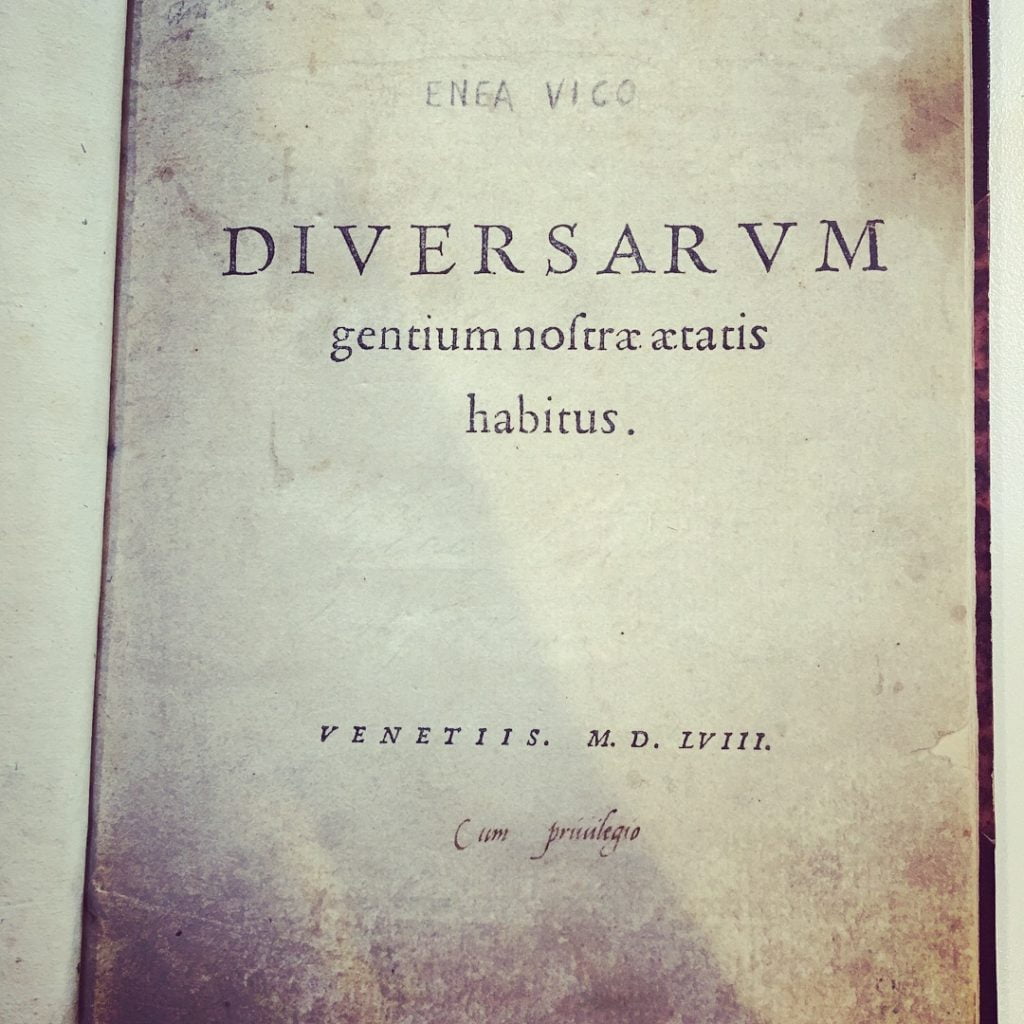

Before meeting up with the rest of the Refashioning the Renaissance team for our Italian study trip in May, I visited Milan to do some research on the print and visual culture related to fashion and dress. The city is of course known as hugely important in the world of fashion today, but it’s also the site of many sources related to fashion in the past. Of interest to me was the collection of early modern prints at the Raccolta delle Stampe ‘Achille Bertarelli’ in Castello Sforzesco and in particular their copy of Enea Vico’s Diversarum gentium nostræ ætatis habitus (Venice, 1558).

Title page from Enea Vico, Diversarum gentium nostræ ætatis habitus (Venice, 1558), Raccolta delle Stampe ‘Achille Bertarelli’, Castello Sforzesco, Milan.

This work is considered by some scholars to be the first printed costume book, and it survives in just a few collections in Europe and the United States.[1] The version in Milan shows 32 men and women from different parts of Europe and western Asia with detailed depictions of their clothing and shoes. Many of the figures that we find in later costume books are very similar to those featured in Vico’s Diversarum.[2] There is also a relationship with Vico’s work the figures in friendship books, which started prior to the production of costume books, as we can see through the comparison of the images below.[3]

‘Militis Germani Uxor’ from Enea Vico, Diversarum gentium nostræ ætatis habitus (Venice, 1558) (Image courtesy of Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam).

‘Tedesche del campo’ from Bartolomeo Grassi, Dei veri ritratti degl’habiti di tutte le parti del mondo, intagliati in rame: libro primo …(Rome: [Bartolomeo Grassi, 1585]), p. 43. Warburg Institute, London.

Detail from Album amicorum of Nic. Engelhardi Argentin, 1601–1700. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

It was so valuable to see Vico’s small, beautiful book in person as well as to have the chance to meet the wonderful staff at the Raccolta Bertarelli and work in such a beautiful and historic place!

View of the reading room at the Raccolta Bertarelli in Castello Sforzesco, Milan.

During my stay in Milan I also went to the exhibition Dürer and the Renaissance between Germany and Italy at Palazzo Reale (21 February to 24 June 2018). This was a wonderful display of many famous and lesser known prints, watercolours and paintings by the German artist Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), and others working in Italy, the Netherlands and Germany. The exhibition did an excellent job of showing how Dürer influenced so many other artists, but also how important his visits to Italy (1494–95 and 1505–06), especially to Venice, were to his work. One of the most beautiful, and famous, paintings on display was Dürer’s Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman(1505). Although this work was created before the timeline for the Refashioning the Renaissance project begins, it offers us an incredible view of a Venetian woman’s clothing from the early-sixteenth century. For example, we can see the fine embroidery on her hair net and sleeves, the bows tied on the silk ribbons on her shoulders and the soft folds in the full sleeves of her gown.

Albrecht Dürer, Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman, 1505. Oil on panel, 35 x 26 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

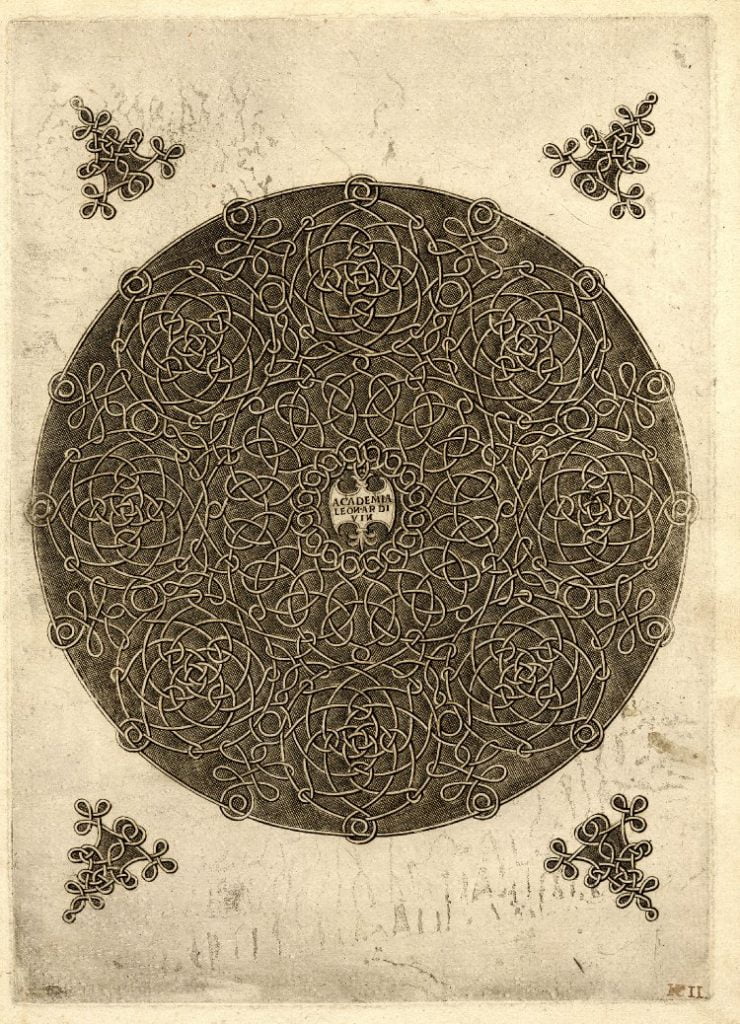

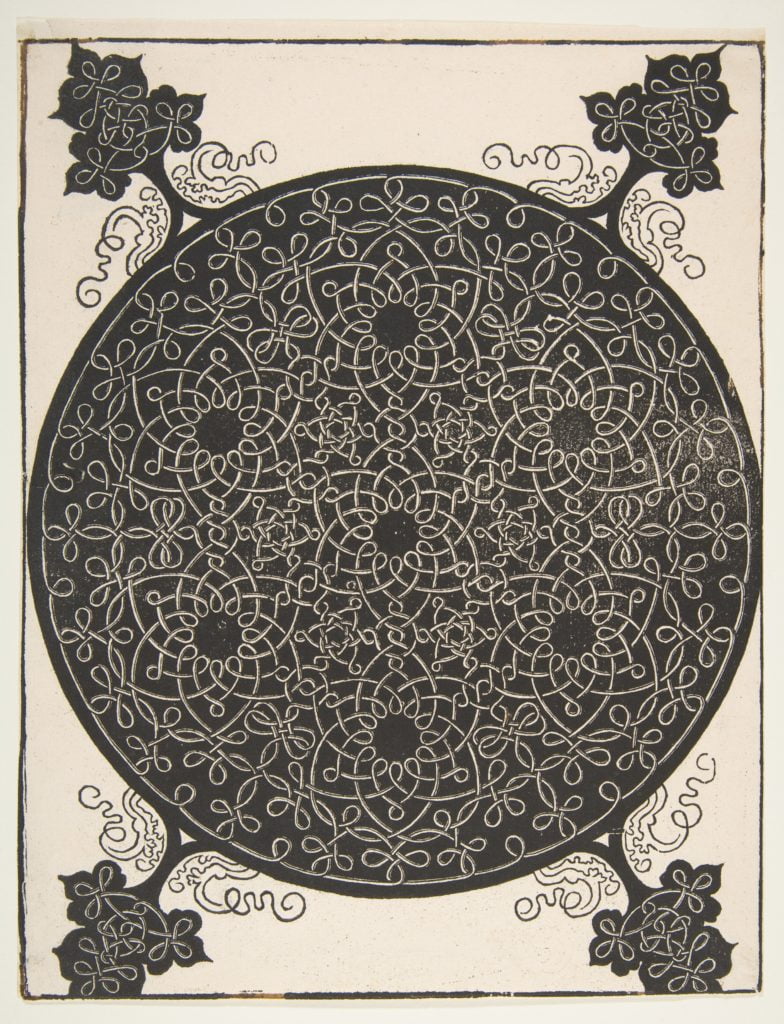

At this time, portraits with a three-quarter view of the sitter were more common in Northern Europe and Dürer and other artists helped to introduce this format to Southern Europe; however, Dürer was also inspired by the work of Italian artists. For example, he created his own designs after Leonardo da Vinci’s famous series of knots. These are beautiful and intricate works in their own right and show one of the ways in which exotic designs spread throughout Europe via print culture. But Dürer’s engravings also relate to the Refashioning the Renaissance project in that they were influential on patterns for embroidery. For instance, Giovanni Antonio Tagliente’s early embroidery pattern book, Essempio di recammi(1530) boasts the inclusion of exotic patterns, such as ‘moresques’.[4] Though not based directly on da Vinci or Dürer’s works, books like Tagliente’s show how print helped to popularise these kinds of designs, and to make them accessible them to non-elite Europeans. For instance, the wives of artisans could use the patterns in these kinds of books to embroider gloves, handkerchiefs or parts of their clothing to make themselves and their family members more fashionable without breaking the bank.

Circle of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), The Fifth Knot. Knot design, with a central shield inscribed ‘Academia Leonardi Vin’, ca. 1490-1500. Engraving, 29.8 × 21.2 cm. British Museum, London.

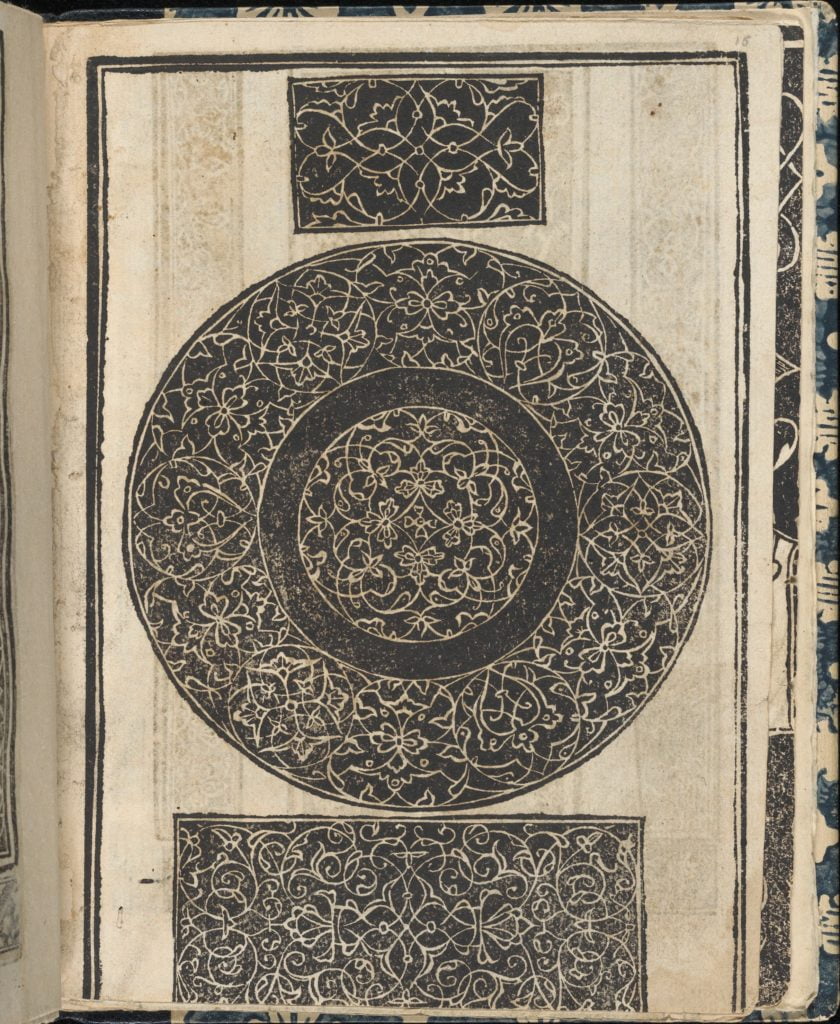

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) (After Leonardo da Vinci or workshop), The Fifth Knot. Interlaced Roundel with Seven Six-pointed Stars, before 1521. Woodcut, 27.3 x 20.8 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Giovanni Antonio Tagliente, Essempio di recammi(Giovanni Antonio di Nicolini da Sabio e i fratelli: Venice, 1530).Woodcut, 19.8 x 15.7 x 1 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The few days that I spent in Milan were full but rewarding. I had the chance to see some beautiful and important printed sources, meet some wonderful archivists and get to know an amazing city. I hope to return to Milan soon to make more of the great resources on offer to researchers interested in the history of fashion and dress.

[1] See, for example, Bronwen Wilson, “Reproducing the Contours of Venetian Identity in Sixteenth-Century Costume Books,” Studies in Iconography25 (2004): 221–74.

[2] For more on the visual similarities between sixteenth-century costume books, see Jo Anne Olian, “Sixteenth-Century Costume Books,” Dress3, no. 1 (January 1, 1977): 20–47.

[3] For more on the relationship between friendship books and costume books, see: Margaret F. Rosenthal, “Fashion, Custom, and Culture in Two-Early Modern Illustrated Albums,” in Mores Italiae : Costumi e Scene Di Vita Del Rinascimento = Costume and Life in the Renaissance : Yale University, Beinecke Library, MS 457, ed. Maurizio Rippa Bonati and Valeria Finucci (Cittadella (Pd [i.e. Padova]): Biblos, 2007), 79–107.

[4] For more on these ideas, see Femke Speelberg, “Fashion & Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520–1620,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin73, no. 2 (2015): 4–48.