Living and working during the Pandemic: Extraordinary times then and now

It has now been 40 days since our university ordered us to work remotely from home, due to spread of the coronavirus in Finland and elsewhere in Europe.

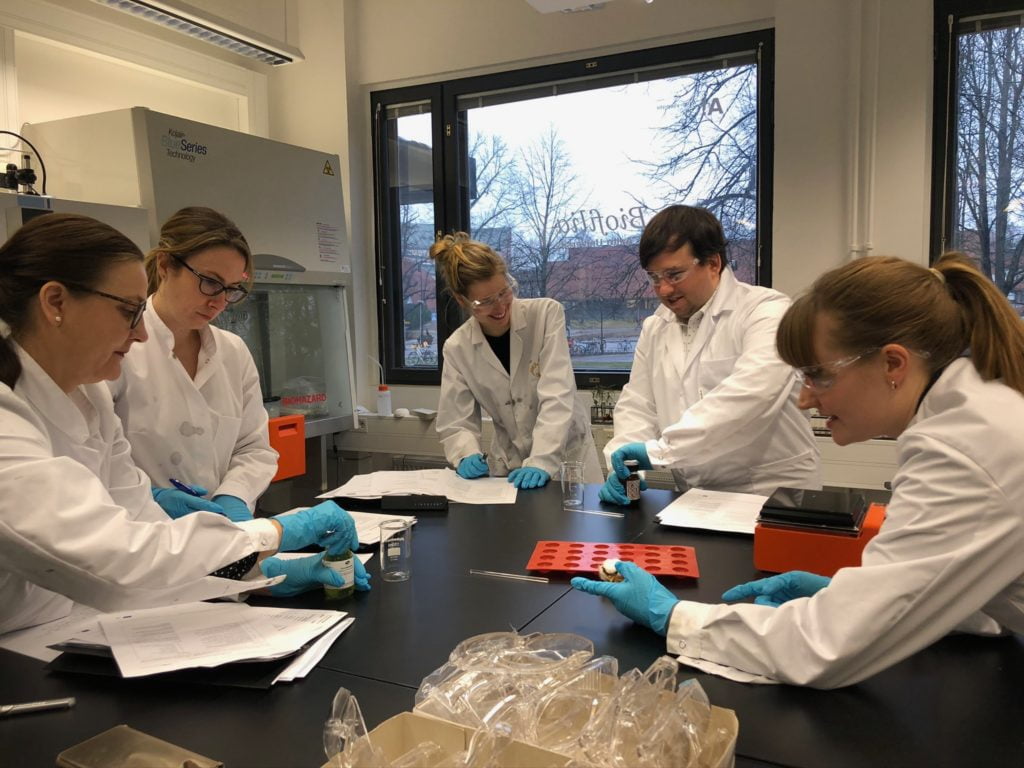

Despite all the challenges that these extraordinary circumstances have brought about into our private and work lives, our team is doing fine. By coincidence, we finished our entire experimental research phase just a few days before the coronavirus crisis unfolded, with our last major experimental workshop on Imitation in Early Modern Clothes and Accessories held at Aalto University in Helsinki in 10–12 March 2020.

Affects of the Covid-19 were already starting to show during our workshop. Most of the face mask had mysteriously disappeared from the Chemistry department.

We are now all working from home, in different countries, and spending our time analysing our project results, reading more about the context of our work, and writing up our results. However, although each one of us as researchers are used to working individually at home, it feels more important than ever to keep in touch and get together. We keep regular online meetings and virtual coffee hours in Zoom and Teams both with our current and previous team members as well as with our research assistants. This provides us an important platform to share our updates and thoughts, not only about work, but also about the experience of being in ‘quarantine’.

Historically, the time frame of 40 days bears significance in the context of pandemic, because sources tells us that the term ‘quarantine’ refers to the Italian words quaranta giorni, 40 days, or quarantina. This was the number of days that all those who travelled to Venice from epidemic areas during the Black Death in the 14th-century were required to isolate.

The plague had devastating effects in Europe, killing from at least one third to a half of the European population in the fourteenth century, and outbreaks of plague continued to ravage towns and the countryside in the West up until the 19th century.

A mob attacking the Quarantine Marine Hospital in New York. Original Publication Harpers Weekly, 1858. Getty.

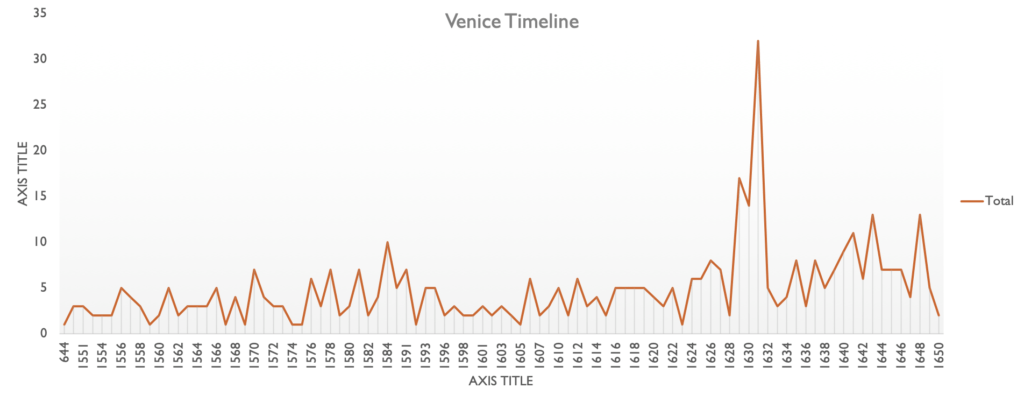

A series of major epidemics occurred also during the period of our study in the Refashioning the Renaissance project, especially during the years of Italian plague in 1629–1631. The shocking effect of the epidemic on Italian population is seen in our archival documentation. The graph below, presenting the number of post-mortem inventories drawn up for our artisans in Venice, shows clearly a high peak during these years, especially in 1631.

The number of post-mortem inventories drawn up for artisans in Venice 1550–1650. Refashioning database.

Venice was particularly vulnerable to the disease, because it was not only a busy trading port but also built upon a lagoon. But the plague ravaged also other Italian cities, such as Florence and Siena.

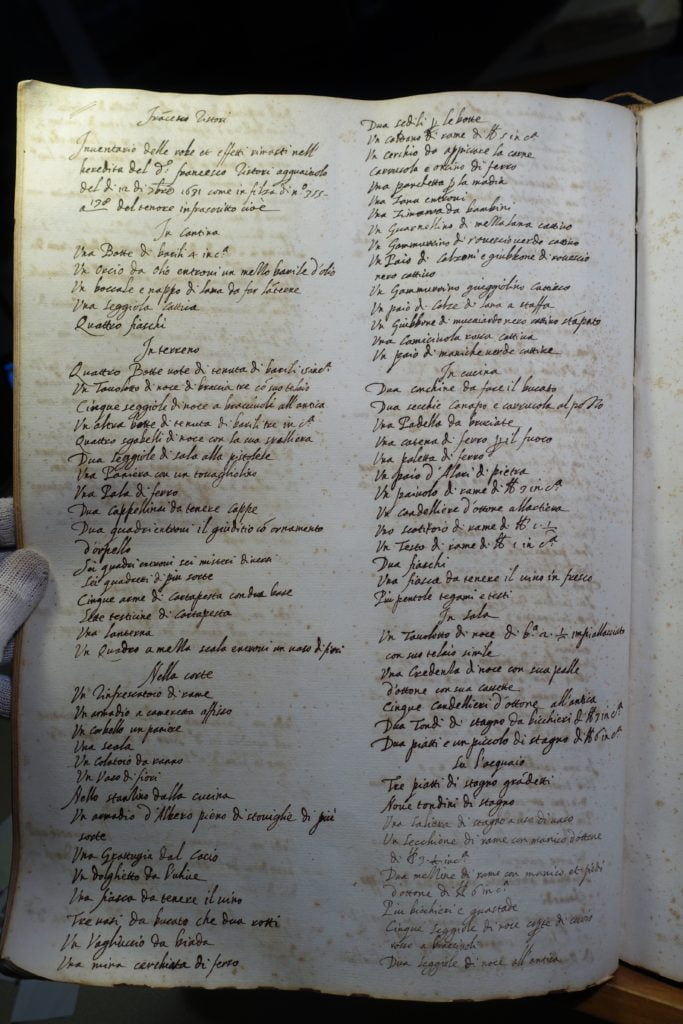

A detailed study of the inventories provides a window to the individual human tragedies during these years. One of the probable victims of the plague was our water seller Francesco Ristori, a resident of the gonfalone San Nicchio (Santo Spirito) at Oltr’Arno in Florence, who died prematurely at the beginning August 1631, leaving minor children behind. We are interested in the waterseller Francesco within out project because he was one of the aspirational artisans who connected with contemporary high fashions through wearing a range of clothing imitations.

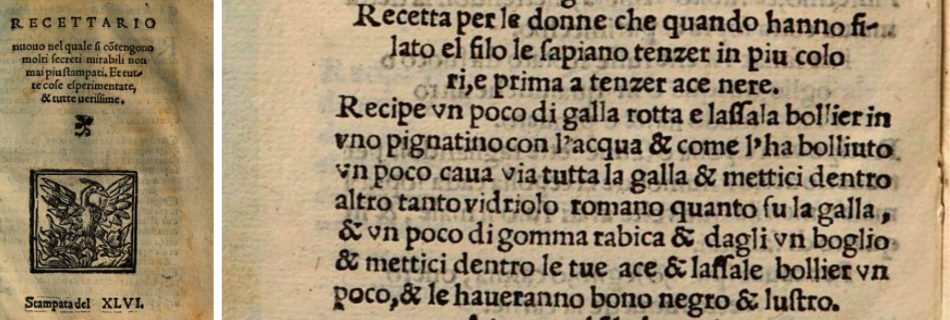

His household goods, recorded on 12 September 1631 in the presence of his wife Maddalena and the witness Giulio di Silvestro Pagami, included, for example, a black, stamped doublet of mock velvet, made in imitation of a more expensive patterned velvet doublet, which our Refashioning the Renaissance project is in the process of reconstructing in collaboration with the School of Historical Dress.

Although we now live and work in special circumstances under many restrictions, our doublet reconstruction project continues and flourishes. It is exciting to see the progress of this interesting project, and it feels comforting to think that, at one point, sooner or later, life will be normal again and we will be able to gather together with our colleagues, friends and family to see what Francesco Ristori’s fashion imitation doublet may have looked like.

Our project is half way through, and it has come time to say farewell to first of our research fellows, economic historian

Our project is half way through, and it has come time to say farewell to first of our research fellows, economic historian