How can we gain access to the hidden meanings and complexities that lie behind historical objects and documents?

The first Refashioning the Renaissance workshop in London, 2-4 October 2018

How can we use written sources, extant objects, and historical hands-on experimentation, to gain access to the meanings and complexities that lie behind historical objects and documents?

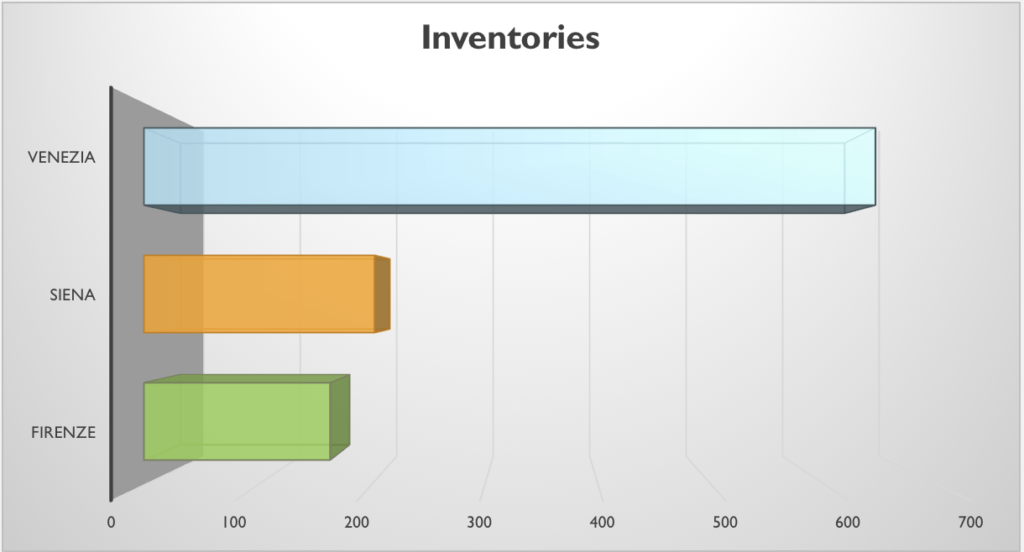

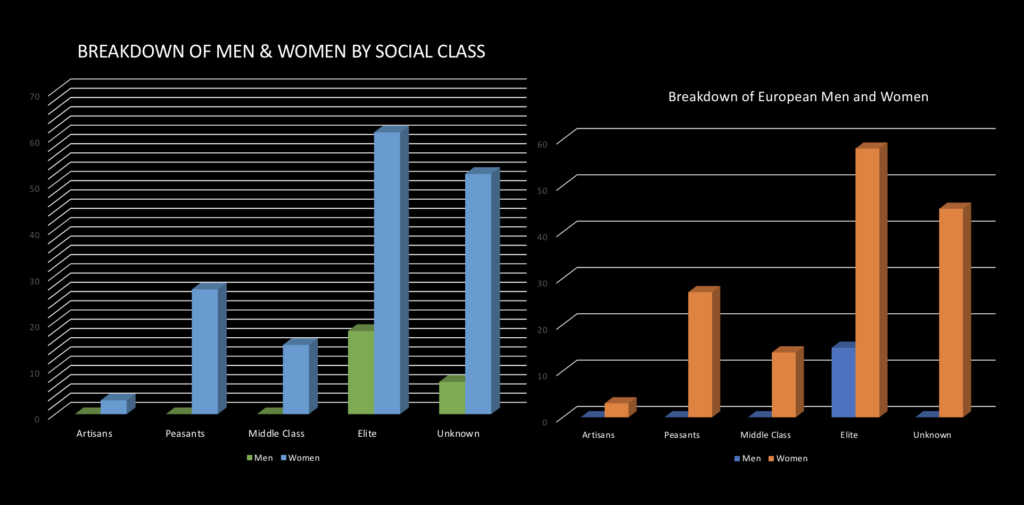

This was one of the main questions that our team discussed at length when we gathered together in London in October for a two-day workshop, organized by our postdoc researcher Michele Robinson. During the two days, we not only looked at our documentary sources, including sixteenth century account books and inventories, discussing how we can best combine quantification with qualitative research. We also thought about how we can connect our documentary data with surviving objects, such as cheap printed recipe books, knitted pullovers and linen undergarments, and use these as a basis for our forthcoming material experimentation and scientific analysis. Therefore, one of the important questions we asked in this session was, what can we actually learn by simply looking at and touching material objects, such as such as sixteenth-century printed advice manuals or a pair of early seventeenth century sailor’s breeches?

Because we are very interested in cheap early modern printed manuals that provided advice on a range of topics, from how to throw a dinner party to how to dye one’s beard black, the Wellcome Collection in London was a perfect place to start. The Institute holds a notable collection of sixteenth and seventeenth century printed books, including books of secret that contain recipes.

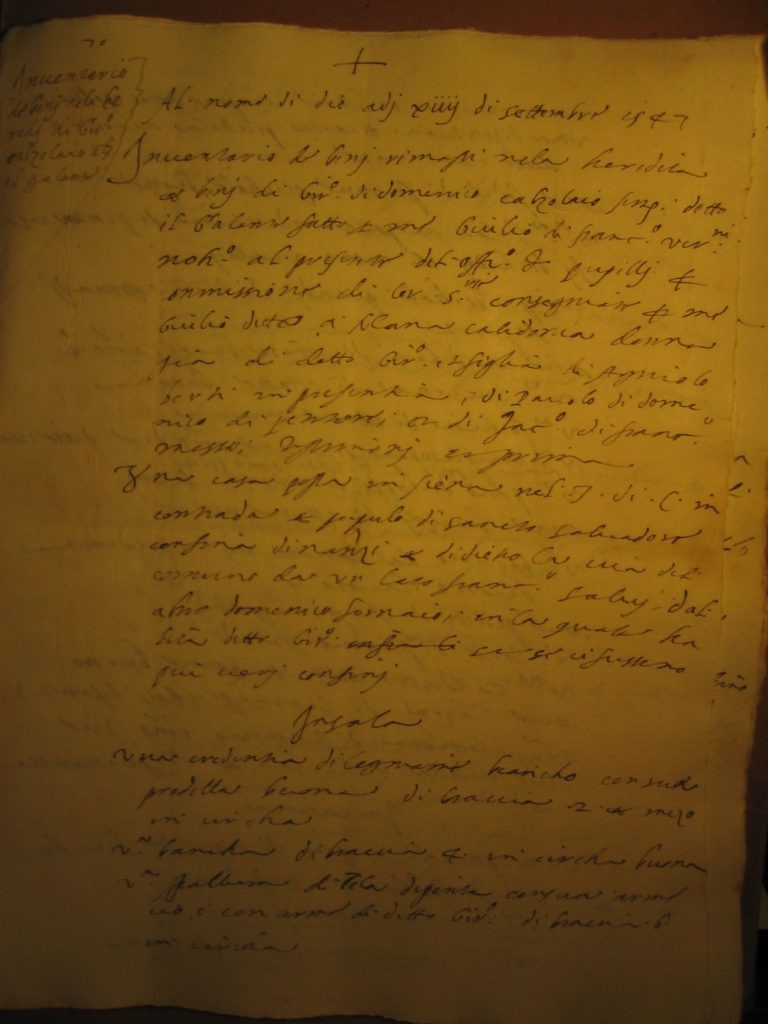

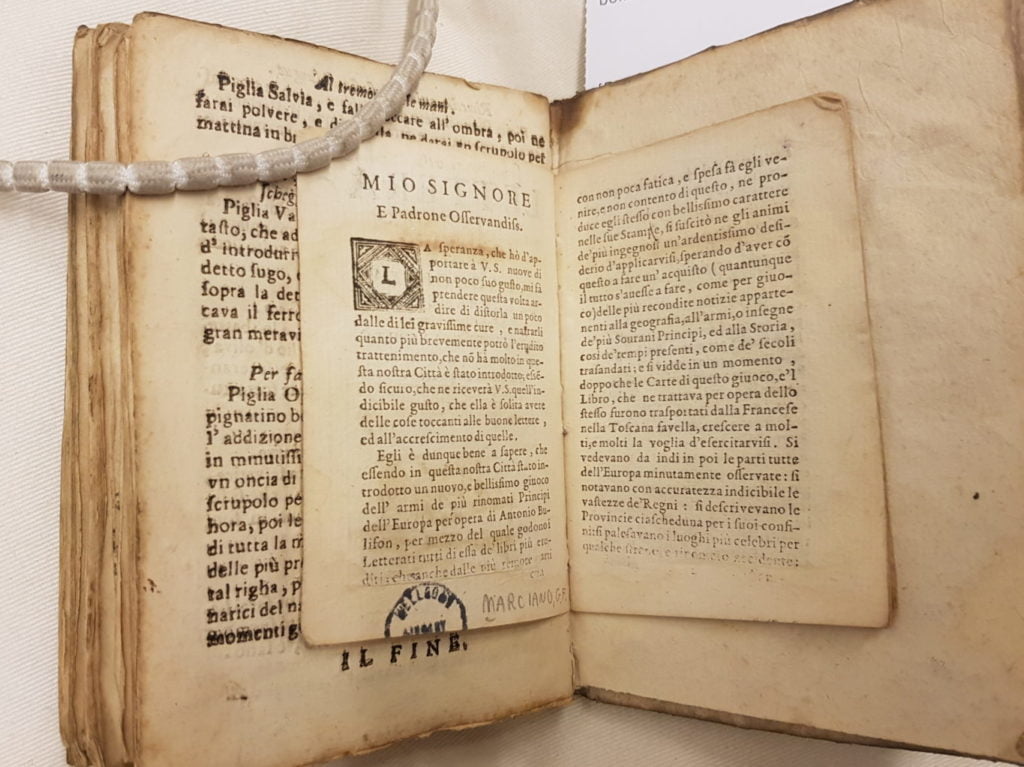

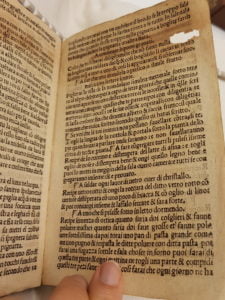

One of the books that we studied was Opera nuova nella quale troverai molti bellissimi secreti, a collection of cheap pamphlets from Venice from about 1540s. Although these small leaflets are now bound together as a book, cheap instructive pamphlets were originally sold individually by street peddlers and book sellers at a low price, and these were, as we can see in the picture below, of different size. The low cost and status of such pamphlets meant that such recipes and instructions were, at least in theory, easily available for our artisans and shopkeepers.

Turning the fragile pages of this simple book revealed small details of tear and wear, and demonstrated that small hand-written inscriptions and notes had been added on the margins of the pages. Although we do not know how books of secret were originally used, this gave a sense that at least some people, at some point in history of these pamphlets, has tested and used these particular recipes.

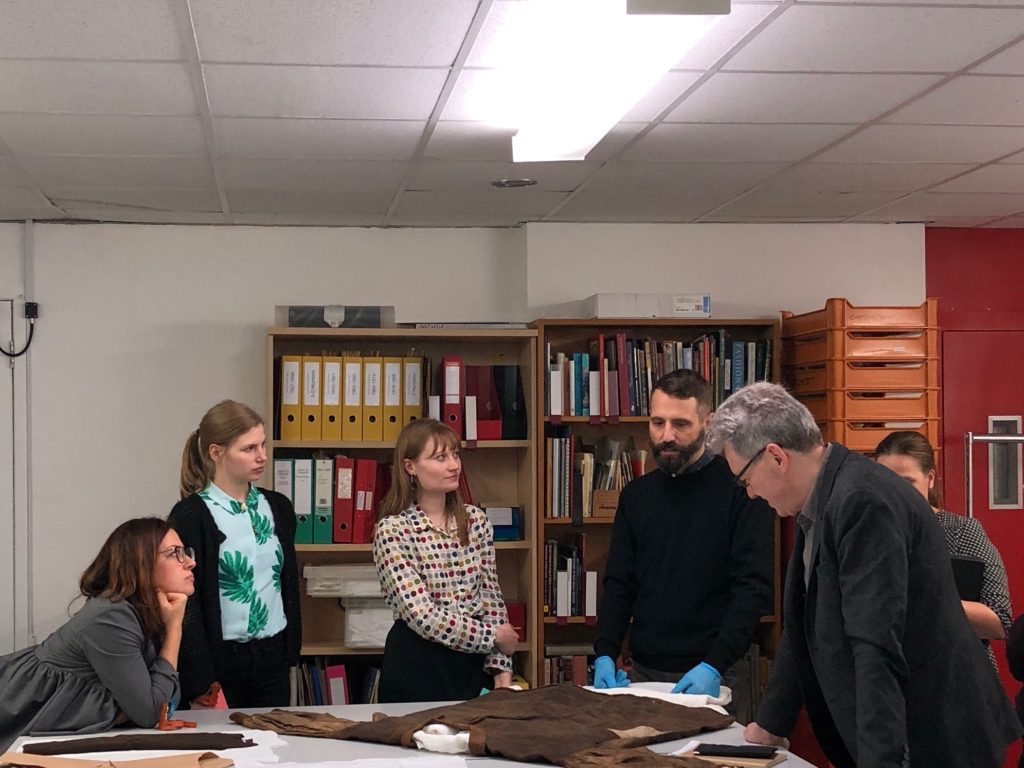

On the second day of our workshop, we had the opportunity to spend an afternoon at the Museum of London storeroom together with the curator Timothy Long, and to engage closely with some extant, less-affluent historical garments from their collections. This allowed us to study in close detail, for example, how a simple sixteenth-century sleeve was constructed, in what way a cap was knitted, lined and fulled, and how a sailor mended his own clothes and marked his breeches with initials or his personal sign. It is sometimes touching to see patched modest garments, and to think about how our artisans and shopkeepers, some of which were relatively poor, may have worn, made and mended these garments, treasured these for their monetary value or beauty, or handed them down as bequests in their wills.

Curator Timothy Long presenting some of the early modern textile objects in the Museum of London collection.

What made these two days very special was that Professor John Styles, who is a member of our advisory board, joined us for the entire two days, and shared his experience and valuable insights about how to combine documentary research with object-based analysis and hands-on experimentation. We were also accompanied, for the first time, by our new postdoc researcher Sophie Pitman. Sophie has been working on historical reconstruction in the Making and Knowing project at Columbia University in New York, and she will lead the experimental part of our team work from January onwards.

John Styles and Michele Robinson.

Sophie Pitman, Mattia Viale, and Stefania Montemezzo.

The two day-workshop was extremely important for our project, because it provided us with some new in-depth insights and inspiration about how we at the Refashioning the Renaissance project can approach documentary sources alongside historical objects, and use them as a basis for material and digital reconstruction and hands-on experiments, which we will start in January 2019.

Our deep interest in the analysis and reconstruction of materials, techniques and objects, alongside visual and documentary sources, connects our work with the research tradition developed in several other international research centres and projects, such as the Netherlands-based ERC-funded project ARTECHNE, led by Sven Dupré, the Making and Knowing Project in Columbia, led by Pamela Smith, the Centre for British Art in Yale, led by Amy Meyers, and the Renaissance Skin Project, led by Evelyn Welch, all of which work, in different ways, at the intersection of craft, art and design history, and history. Our intention is to continue our work within this tradition, and to think about how we can further develop this historical approach by connecting historical experimentation with digital reconstruction. This framework, we hope, will allow to establish a set of new methodologies in material culture history studies that allows us to gain better access to the skills, sophistication and hidden meanings that were involved with objects, materials and techniques in this period.