In November, during my recent research trip in the state archives of Siena with our researcher Stefania, we decided to take a walk in the Sienese neighbourhood of Onda. This central contrada south from Piazza del Campo, originally called San Salvatore, used to be a popular neighbourhood among Sienese artisans in the Renaissance period. By 1531, nearly two thirds of San Salvatore’s inhabitants consisted of artisans or small local entrepreneurs, including painters, innkeepers, musicians, tailors and mercers to smiths, carpenters, masons, shoemakers, and weavers.

Street view in San Salvatore

One of the inhabitants of San Salvatore was the shoemaker Girolamo di Domenico who lived here in the first half of the sixteenth century with his children and wife Calidonia. His story invites us to think of the harsh economic conditions of many of the lower ranking artisans that we are studying in this ERC project. Tax records tell us that, in 1531, his taxable wealth was a modest 175 lire and the family’s economic circumstances did not improve in the following years. Girolamo died in 1547, leaving behind minor children. While there is no trace of what happened to the family after the shoemaker’s death, we can only hope that Girolamo’s brother Giovanni and someone named Girolamo di Bartolomeo Salvestri, described as Girolamo’s ‘relative’ (parente), both shoemakers, protected the widow and her children from falling into complete poverty.

As Stefania and I walked along the narrow, twisting streets of San Salvatore, looking at the original architectural features of the buildings that revealed where shops had originally been located, we were wondering whether clothing and fashion mattered on these streets, where many families struggled to provide just the basic living for their families.

While questions of cultural meaning and value in the absence of artisans’ own words are difficult to evaluate with precision, archival evidence, such as household inventories, allow us to access individual’s personal wardrobes and gain knowledge about ownership of clothing at most levels of society.

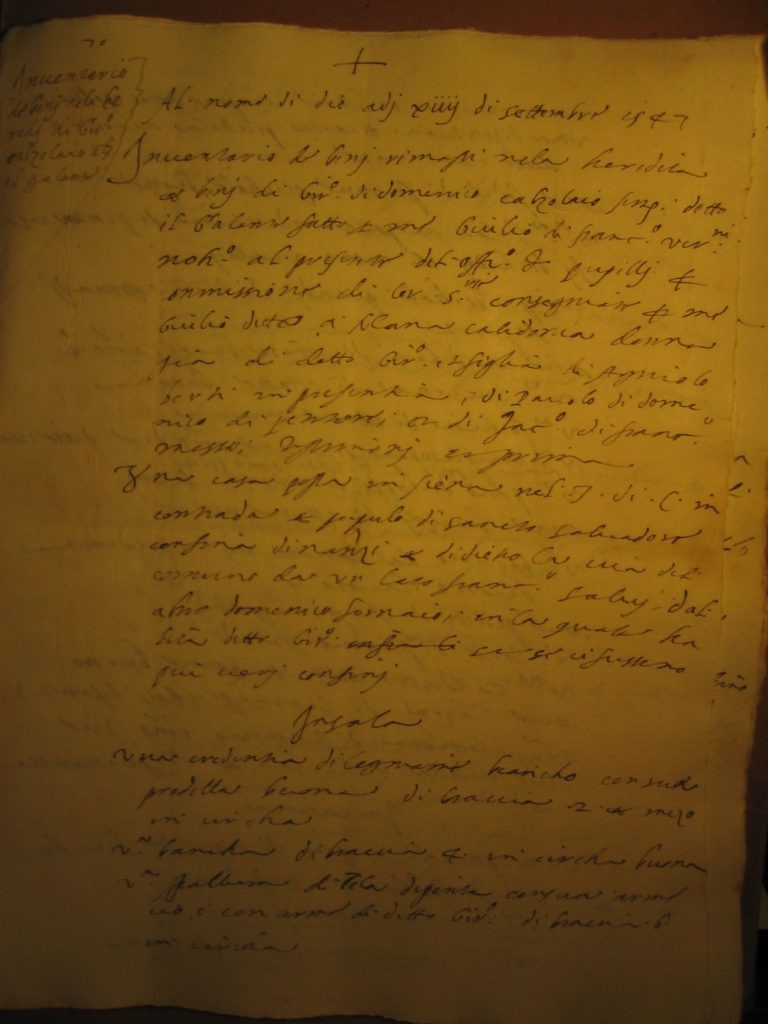

The shoemaker Girolamo’s inventory was drawn up a few days after his death on 14 September, 1547. The list of clothing that belonged to him and his wife included 26 dress items (pairs of hose, hats, shirts, skirts, jackets, under- and over-dresses and cloaks) that were stored in five chests. This indicates that the shoemaker Girolamo and his wife both had two or three sets of clothes.

Page from Girolamo di Domenicos inventory

Although a fair number of their garments were modest, often described as ‘sad’, ‘old’ or ‘worn out’, the shoemaker Girolamo and his wife Calidonia owned some garments that made it possible for them in special occasions to strip off their work clothes and dress up. The five chests of clothing in Girolamo’s house included relatively fine dress items, such as a white men’s doublet, a pair of black woollen breeches, a woollen cloak and a black satin beret, as well as a pair of black detachable women’s satin sleeves, a woollen cloak and two purple skirts described in the document as ‘fine’. Furthermore, some of these clothes were decorated and made from fine materials. One of the shoemaker’s wife Calidonia’s purple dress, decorated with a black velvet band and large puffs in the upper part of the sleeve, was made from pavonazzo-coloured cloth. This purple colour, obtained from valuable kermes dyestuff, was preferred also by patrician men and women, not only because it was expensive, but also because it was also a symbol of power and authority. Pavonazzo became forbidden from lower classes by sumptuary law in Siena in 1588.

Such garments were treasured objects among artisan families and may have been acquired in connection with marriage. Yet, the presence of fine garments such as Girolamo’s white doublet and black woollen cloak, or Calidonia’s satin sleeves and pavonazzo dress demonstrates that Renaissance dress and dressing up mattered at all levels of society, even among the poorer quarters of the city. Everyone wanted to look good in festive occasions and on Sundays at Church!