Early modern visitors to the Rialto market in Venice report a dazzling abundance of goods for sale. As the Englishman Fynes Moryson describes in his travel account, Itinerary (1617): ‘The goldsmiths shoppes lie thereby, and over against them the shoppes of the Jewellers, in which Art the Venetians are excellent’ (191).He and others were surely tempted as they passed by their glittering displays.

Most of these precious materials came to Venice from across Europe and the wider world. Some goldsmiths and jewellers emphasised the foreign and mysterious origins of gemstones, perhaps as a marketing tool. Rimondo Rimondi operated his shop ‘under the sign of the Turk’ in the neighbourhood of San Severo to the east of the Rialto district. Here customers could purchase Bohemian garnets, Baltic amber and white sapphires from India.[1]

We don’t know what Rimondi’s sign looked like, but ‘Turks’, men from the Ottoman Empire, were often represented with turbans like that worn by the Sultan Mehmet II in this portrait. Gentile Bellini, The Sultan Mehmet II, 1480. Oil on canvas, possibly transferred from wood, 69.9 x 52.1cm. The National Gallery, London.

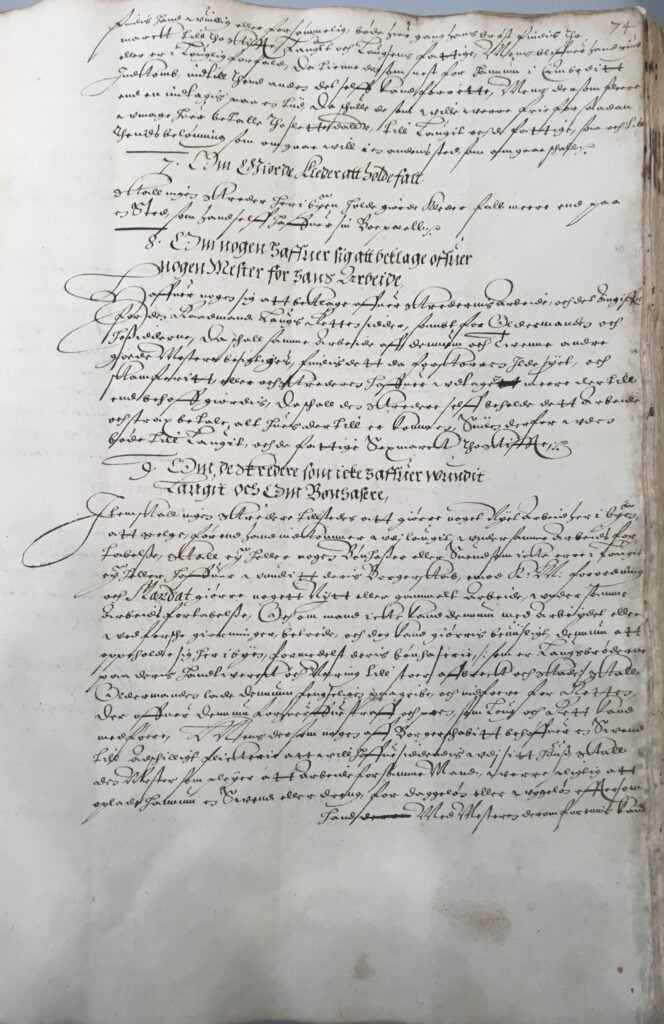

Rimondi’s competitors also offered gems, precious metals and semi-precious stones from around the world. Benetto Bellotto, who had a shop near the Rialto bridge under the sign of the Magdalen, sold bracelets ‘in the Turkish style’, Scottish pearls and assembled gems called doublets (doppie) from Spain.[2] In Alvise Belliardi’s shop you could find diamonds, agate, lapis lazuli, turquoise and emeralds—all imported from afar—for sale. The goldsmith also had ‘two table-cut rubies and another cabochon ruby set in a gold ring in the Turkish style (ala Turcehscha)’. Finally, Belliardi also seems to have stored gems for friends or clients when they were away. He had, ‘in a box a string of seventy pearls, marked with a lead marker, said to belong to Abraham Turcho Granatino, who is in Constantinople’. [3]

Lapis lazuli is a semi-precious stone that was imported into Europe from what is now Afghanistan. It was used to make very expensive blue pigments as well as in jewellery. Portrait of Cosimo de’ Medici, c. 1567-9. Carved lapis lazuli, 5.5 x 4.7 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

There was a definite air of exoticism around gemstones and jewels that added to their desirability and value. But behind the sparkling facade were dark secrets; these materials were often mined, fished or otherwise retrieved in ways that harmed human and animal life as well as the environment. And, the gems and jewels that came with ethical implications were worn not only by the wealthiest members of society, but those lower on the social hierarchy as well. The inventories gathered for the Refashioning the Renaissance project show that many artisans owned gemstones and other precious materials that were financially and environmentally costly.

This painting on copper shows an idealised and mythological take on the fishing of pearls and coral in the New World. Jacopo Zucchi, The Coral Fishers, 1585. Oil on copper, 55 x 45cm. Galleria Borghese, Rome.

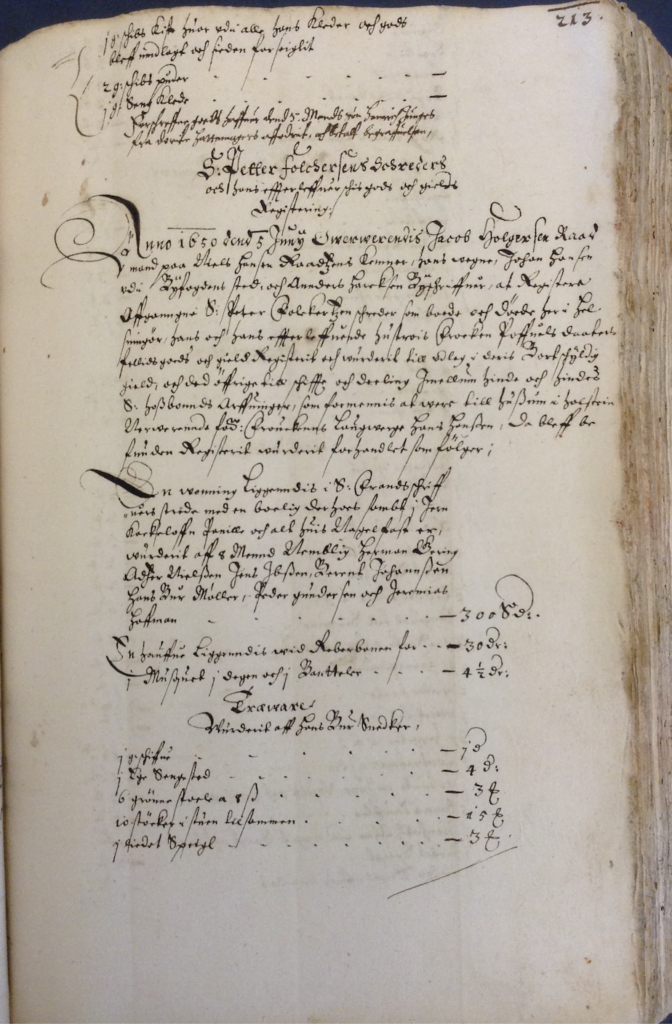

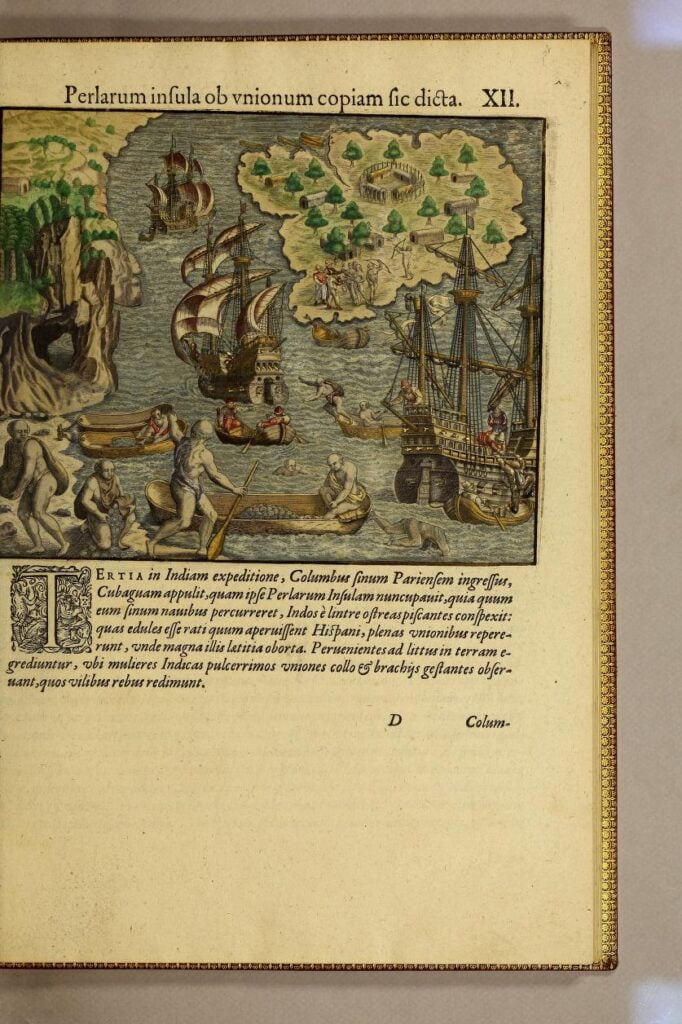

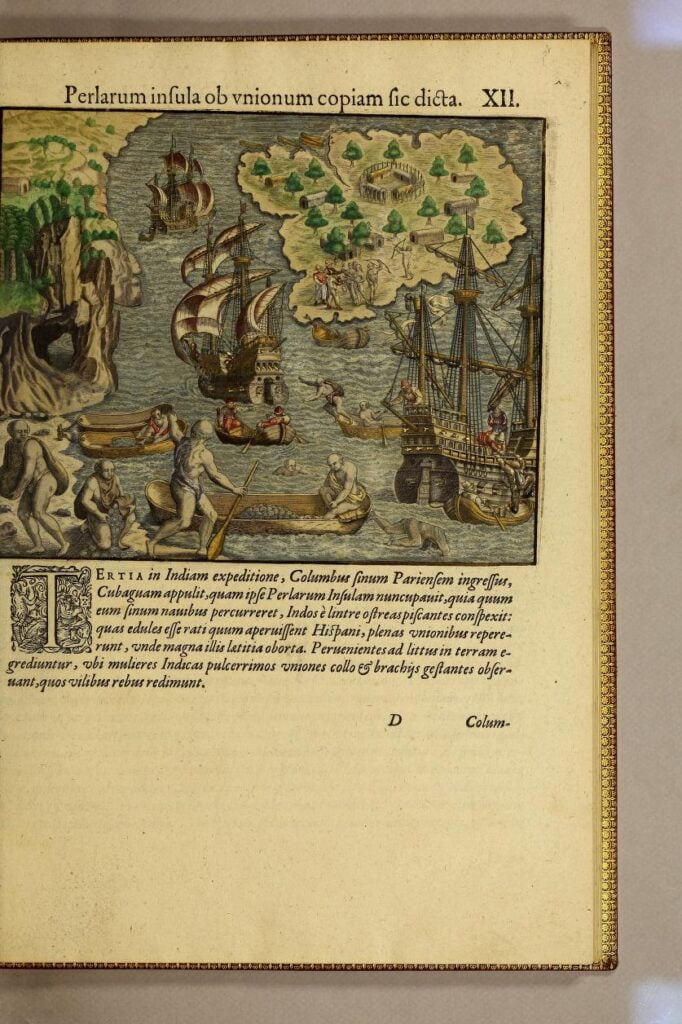

Pearls in particular appear in great numbers in these documents especially in the form of necklaces and bracelets, and indeed pearls were coveted by people across early modern Europe. Until the end of the fifteenth century, most pearls came to Europe from the Persian Gulf, Red Sea and Gulf of Mannar, with freshwater pearls largely coming from Scotland. But, on his third voyage to the Americas in 1498, Christopher Columbus realised pearls could be fished off of the coast of what is now Venezuela, opening up a new and plentiful source for the European and Asian demand for pearls. Spanish-run pearl fisheries quickly depleted communities of indigenous divers, having enslaved and worked many of them to death. To feed the European market, and to fill Spanish coffers, enslaved men from the west coast of Africa were brought to the Americas to dive for pearls.[4]

Reports from Spanish missionaries and other Europeans detail the appalling treatment of the African and indigenous divers, both in terms of their living and working conditions. Bartolomé de Las Casas (c. 1474–1566), for instance, recorded in his Historia de las Indias (History of the Indies) that divers were beaten if they took too long fetching pearls from the sea floor. On these deep dives men risked being attacked by sharks and other marine predators, as well as drowning, haemorrhaging and blown ear drums. According to Las Casas, many died after only a few days of this work, and those who didn’t saw changes to their hair colour and burned wounds due to prolonged time in cold salt water.[5]

This detail of Theodor de Bry’s engraving shows pearl divers off of Cubagua, near what is today Venezuela. From Girolamo Benzoni’s Americae pars quarta (Frankfurt am Main: Ioannis Feyrabend, 1594), plate XII.

In addition to taking human lives, pearl diving also killed an enormous number of animals. Pearls are found in about one in 10 000 oysters and it’s estimated that over the most lucrative thirty years of fishing off of the coast of the island of Cubagua alone, 1.2 billion oysters were harvested.[6] Their shells were pried open, pearls removed and the remains tossed on the beach; some contemporaries wrote about the incredible stench from the discarded oysters and all the flies this attracted – a far cry from even the smelliest of canals in Venice, where many pearls ended up in workshops like Rimondo Rimondi’s.[7]

In addition to the loss of human and animal lives, pearl fishing also devastated the local environment. Harvesting tens of thousands of oysters over a fishing season drastically altered the marine ecosystem. Some entrepreneurs also proposed dredging the sea bed to more quickly collect oysters, though this was not often practiced in the Americas due to the damage it caused, which prevented recovery of the oyster beds over time.[8]

The large, drop-shaped pendant pearl on this necklace is so famous it has a name: Le Peregrina, The Wanderer. It came into the possession of the Spanish crown having been fished from waters off of Panama in 1579. It passed through the hands of Napoleon’s elder brother, Joseph, and eventually Elizabeth Taylor. In 2011 it was sold at auction as part of this necklace for 11,842,500 USD!

Pearls from the Americas flooded the European market in waves beginning in the early sixteenth century. And, the Portuguese gained control of pearl fisheries in Indian Ocean and Gulf in 1507, which meant more pearls than ever were coming directly into Europe.[9] This abundance drove prices down, making pearls more affordable, even if they were never cheap. One contemporary noted: ‘Now everyone wears pearls and seed pearls, men and women, rich and poor’. This observer pondered whether pearls were so popular, ‘because they are brought from another world […] or perhaps it is because they cost the lives of men.’[10]

Pearls certainly carried with them reminders of the sea and maritime power, even for those who would never visit the waters from which they came. For example, a stone-cutter in Siena had a pair of little gold pendants with ships and six little baroque pearls in 1646.[11] These may have been similar to the pendants owned by a weaver, also from Siena, who had, ‘a pair of little pair of ship-shaped pendants with six pearls each and six more little pearls with a red stone in the middle’, in 1640.[12] There are several examples of these kinds of pendants in the Refashioning documents and in museum collections today, suggesting they were quite popular.

Pendant in the form of a ship, 16th century, possibly Italian. Enameled gold and pearls, 16 grams. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

But, if ship pendants decorated with pearls made reference to the sea, maritime power and increasing European dominance over other continents, they elided the death and destruction that came in the wake of pearl fishing. This made it easier for consumers to ignore or remain ignorant about from where their pearls came and at what cost. Similarly, today’s pearls hide their origins well. Natural pearls—those that occur and grow in wild oysters and mussels as they coat parasitic worm or other foreign bodies (but not sand) with nacre (also called mother of pearl)—are now very rare. Nearly all pearls on the market today are ‘cultured’ or grown inside of salt- or freshwater molluscs through human intervention. A young oyster or mussel is forced and propped open with a wooden wedge and a scalpel is used to make an incision in its reproductive organ. Then a nucleus—often a bead of pearl, mother of pearl or shell—and a piece of mantle from another mollusc are implanted; the animal is then allowed to close. Over time, it secretes nacre (mother of pearl) around the nucleus, as it would any other irritant in nature. After around three and a half years a saltwater pearl can be harvested if the operation was a success. This process usually results in the formation of one or two pearls but freshwater mussels can produce between thirty and fifty pearls at once, though over five years rather than three. After the harvest, some animals are killed and others put through the process again.

Pearl farming has drawn criticism from both animal welfare groups and those concerned with the environment. Mussels feed on plankton, the growth of which is encouraged by farmers through the addition of manure, soil and other pollutants to freshwater. Oysters, though, are more sensitive to their environment and changes within it. They won’t produce pearls if conditions aren’t perfect, so farmers monitor the saltwater environment closely. This is similar to those running pearl fisheries in the early modern period, where there was an understanding that the waters could be over-fished and that changes to the ecosystem impacted the number and quality of pearls produced. And, as in the past, diving for pearls today can be difficult, dangerous and even deadly work.

This devotional pendant features pearls made from lampworked glass – a convincing alternative to real pearls? Devotional pendant, 16th century (and later), Italian or Spanish. Cut and polished, reverse-painted, reverse-gilt, and reverse-silvered rock crystal; lampworked glass; gold. Diameter 3.3 cm. Robert Lehman Collection, 1975. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

‘Do we get most bodily pleasure from luxuries that cost human life?’ Pliny the Elder (23–74CE) asked about pearls in his Naturalis Historia written nearly 2000 years ago.[13] The question continued to be relevant into the early modern period, when people were enslaved and died, billions of animals perished and severe environmental damage was caused all to feed desire for pearls and wealth generated from them. Today, modern versions of these problems persist, though some efforts are being made to farm and harvest pearls in more ethical, eco-friendly ways. There are also alternatives to cultured pearls, such as those made from plastic, cotton and glass. In the early modern period, too, shoppers could choose pearls made from clay, shell, glass or enamel to suit their budgets, desires and sensibilities.

[1] Archivio di Stato di Venezia (hereafter ASV), Giudici di Petizion, b. 350, f. 13. 22 April 1626.

[2] ASV, Giudici di Petizion, b. 358, f. 45, 12 December 1642.

[3] ASV, Cancelleria inferiore, Miscellanea, b. 41, f. 30, 10 August 1570, fols. 5r and 7r. On the global trade in gems see Michael Bycroft and Sven Dupré, eds., Gems in the Early Modern World: Materials, Knowledge and Global Trade, 1450–1800 (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

[4] Mónica Domínguez Torres, “Pearl Fishing in the Caribbean: Early Images of Slavery and Forced Migration in the Americas,” in African Diaspora in the Cultures of Latin America, the Caribbean, and the United States, ed. Persephone Braham (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2014), 73–82. Nicholas J. Saunders, “Biographies of Brilliance: Pearls, Transformations of Matter and Being, c. AD 1492,” World Archaeology 31, no. 2 (October 1999): 243–57, 250-1; Molly A. Warsh, American Baroque: Pearls and the Nature of Empire, 1492-1700 (UNC Press Books, 2018), 38-40.

[5] Molly A. Warsh, American Baroque: Pearls and the Nature of Empire, 1492-1700 (UNC Press Books, 2018), 43. Mónica Domínguez Torres, “Pearl Fishing in the Caribbean: Early Images of Slavery and Forced Migration in the Americas,” in African Diaspora in the Cultures of Latin America, the Caribbean, and the United States, ed. Persephone Braham (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2014), 73–82

[6] Warsh, American Baroque, 62.

[7] Warsh, American Baroque, 155.

[8] Warsh, American Baroque, 65-67.

[9] Robert A. Carter, Sea of Pearls: Seven Thousand Years of the Industry That Shaped the Gulf (London: Arabian Publishing, 2012), 61-89.

[10] Warsh, American Baroque, 81.

[11] Archivio di Stato di Siena (hereafter ASS), Curia del Placito, b. 283, f. 266, 3 September 1646, fol. 18v.

[12] ASS, Curia del Placito, b. 280, f. 111, 24 April 1640, fol. 224r.

[13] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, a Selection, trans. John F. Healy (London: Penguin Books, 1991), 135.