Sumptuary Laws in Denmark: Om Drecht och Klædebon, 1558

In researching fashion and textiles in the artisan groups of Scandinavia, sumptuary laws are both important and interesting in terms of looking into what kinds of restrictions the king and the nobility found necessary to implement in society to maintain the social hierarchical order. Dress and fashion were ways people could signal their place in the social hierarchy, and the need to implement sumptuary laws, one might argue, was a response to a perceived threat from the masses of society.

In working with fashion among the lower groups of society, these laws are excellent in getting a glimpse into the social hierarchy of the Danish renaissance period, and especially how the society elite perceived the lower groups of society. Many sumptuary laws were issued in Denmark in the period of 1550-1650, but to what extent the over excessive consumption was an actual problem in the population, we do not know.

Christian III of Denmark, from the Bible of Christian III, 1550.

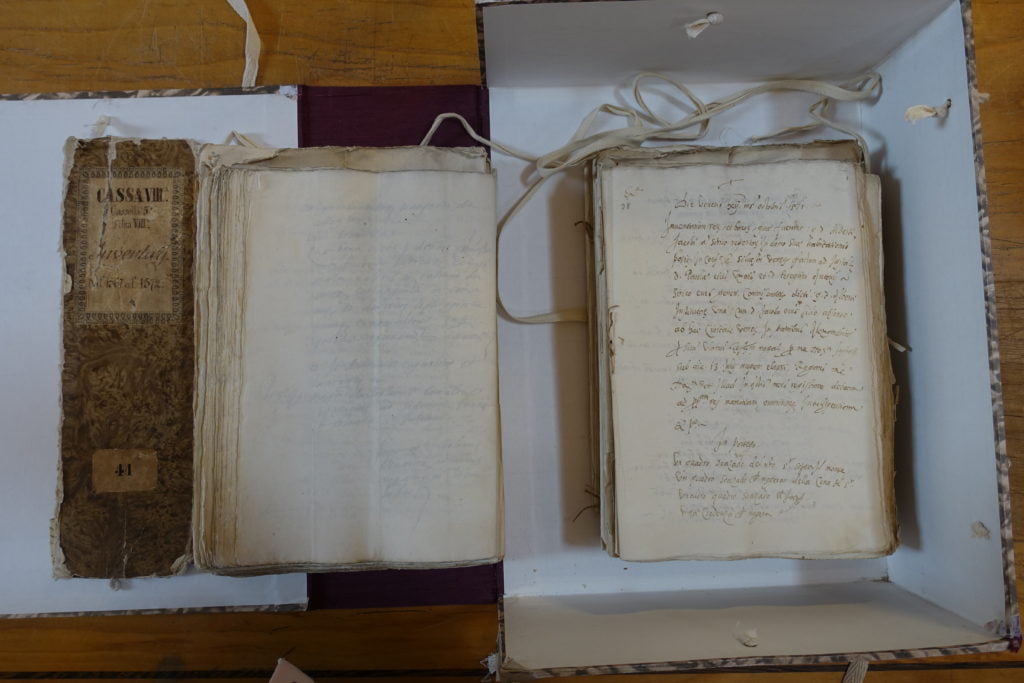

In considering the laws, I am especially interested in what kinds of restrictions were laid upon the ordinary people. One of the first laws in the beginning of the period under investigation is a law from Denmark. In 1558 Christian III of Denmark issued a law called the Koldingske Recess. Within the law is the section called Om drecht och klædebon, where regulations on dress and textiles is stated. These regulations give information on what types of textiles the elite considered as luxury, and what kinds of textiles were in circulation in society, but they also tell what lower groups of society were restricted from using.

In general, the law prohibited all people from wearing luxury textiles such as gyldenstycke and sølfstycke (silk embroidered with gold and silver threads) and blyant silk (a valuable kind of silk together with any other kinds of silk embroidered with gold or silver thread). The law also prohibited the usage of embroidered hair pieces, pearls on headwear or neckwear, gold trimmings, silver trimmings, together with gold and silver lace.

Concerning ordinary people, it is stated that no unfree people, burghers or peasants, or the unfree man’s wife or their children, are allowed to wear velvet, damask, or silk. However, an honourable not noble woman, presumably an unmarried woman, was allowed to wear a plain silk or velvet ribbon around her head. Does this mean that the king and his servants had actual experienced these groups of lower stand wearing these kinds of textiles? And is this a sign that these people had access to these kinds of materials? These are some of the question that are interesting to look further into.

What the regulation also tells us, is that it was the responsibility of the hospital to collect the fees of people who broke the law. Working with these laws, however, we have to take in consideration that we do not know whether people ever were prosecuted for wearing forbidden items, or whether they might have adapted or rearranged their need for luxury, so they would not get prosecuted.

Even though there is a lack of knowledge on how these laws were enforced in this period, and we do not know how effective they were in real life, these laws offer great material when working with fashion and textiles, and can be used to accquire information on many different aspects on early modern Scandinavia.

Literature:

Dalgaard, Hanne Frøsig: Luksusforordninger – 1558.1683,1736,1783,1783 Og 1799. Tenen – Dansk Tekstilhistorisk Forening 2015.

Secher, V. A. Forordninger: Recesser Og Andre Kongelige Breve, Danmarks Lovgivning Vedkommende 1558-1660. Vol. 1: Selskabet for Udgivelse af Kilder til Dansk Historie, 1887-1888.