Linen shirts were important garments in the early modern period. They helped to keep the body clean by drawing away sweat and oil, but also gave structure to sleeves, bodices and doublets. From the early sixteenth century, shirts began to expand beyond the boundaries of these garments, peeking out through slashes in sleeves, as well as at necklines and the wrists. Lorenzo Lotto’s Portrait of a Lady as Lucretia, (1530-32), for example, shows her white linen shirt through the fur-trimmed slashes near her elbows. The top of her shirt is visible along the low neckline of her dress, and at her wrists.

Figure 1. Lorenzo Lotto, Portrait of a Lady as Lucretia, 1530-32. Oil on canvas, 96 x 111 cm. National Gallery, London.

This extension of linen offered a sort of canvas for ornament, like embroidery with silk or metallic threads, complex works of lace and carefully pleated and shaped ruffles. For example, Giovanni Battista Moroni’s A Gentleman in Adoration before the Madonna (1560) shows detailed embroidery around the collar and cuffs of the man’s shirt, which have been neatly folded over in order to display this fine work.

Figure 2. Giovanni Battista Moroni, A Gentleman in Adoration Before the Madonna, 1560. Oil on canvas, 60 x 65 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington.

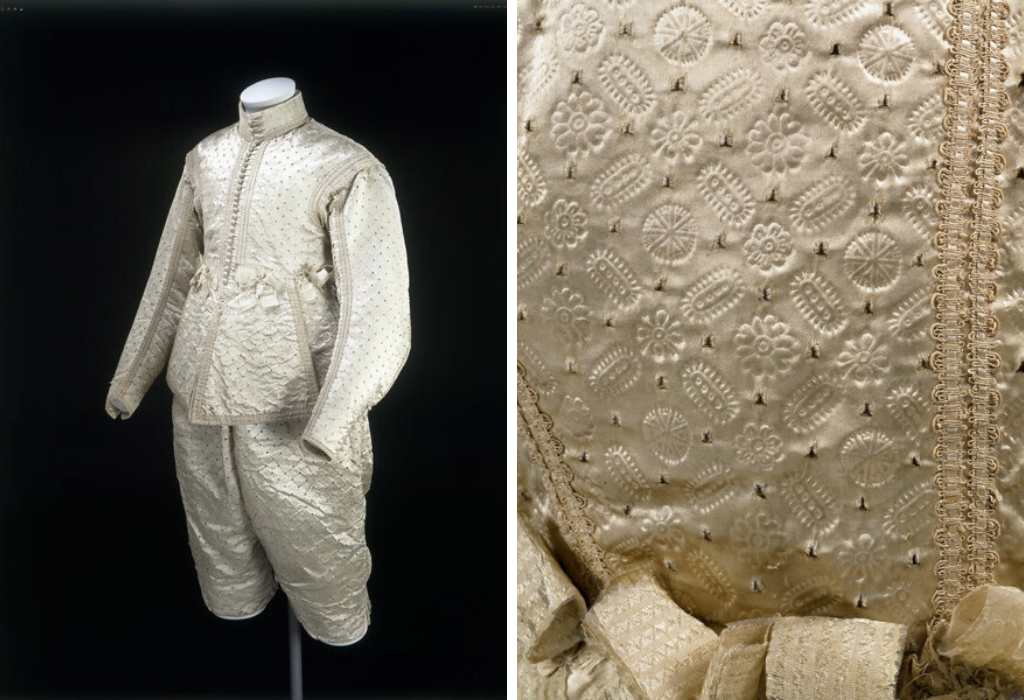

In the 1560s, collars and cuffs developed into detachable pieces that could be cleaned and set separately from shirts. These were made and set in a wide range of styles, which could be mixed and matched to create different looks. For example, Justus Sustermans’s portrait of Cosimo II de’ Medici, Maria Maddalena d’Austria and their son, Ferdinando (c. 1640), shows three different options for how a very wealthy Florentine might decorate their neck and wrists.

Figure 3A. Justus Sustermans, Cosimo II de’ Medici, Maria Maddalena d’Austria and Their Son Ferdinando, c. 1640. Oil on canvas. Galleria degli Uffizi, Corridoio Vasariano, Florence.

On our left is Maria Maddalena, with a standing, heavily starched collar made of very fine lace in at least two layers, which looks to be folder under along her collar bone and sitting on top of more lace, perhaps that decorated the collar of her shirt. In the centre of the painting is Cosimo. His collar also features layers of lace, but these have been shaped into ruffled loops and circle his neck completely.

Figure 3B. Detail from Cosimo II de’ Medici, Maria Maddalena d’Austria and Their Son Ferdinando showing Cosimo and Maria Maddalena’s collars.

The lace pattern echoes that on Maria Maddalena’s wrists – her cuffs have a pattern different to that on her collar.

Figure 3C. Detail from Cosimo II de’ Medici, Maria Maddalena d’Austria and Their Son Ferdinando showing Maria Maddalena’s cuff.

Finally, on our right is Ferdinando, with a collar that settles down onto his shoulders and features very fine lace, which is nearly transparent, and that is attached to linen or perhaps silk. The same style is also found on his cuffs, with a pleated band of white linen or silk and very fine lace.

Figure 3D. Detail from Cosimo II de’ Medici, Maria Maddalena d’Austria and Their Son Ferdinando showing Ferdinando’s collar.

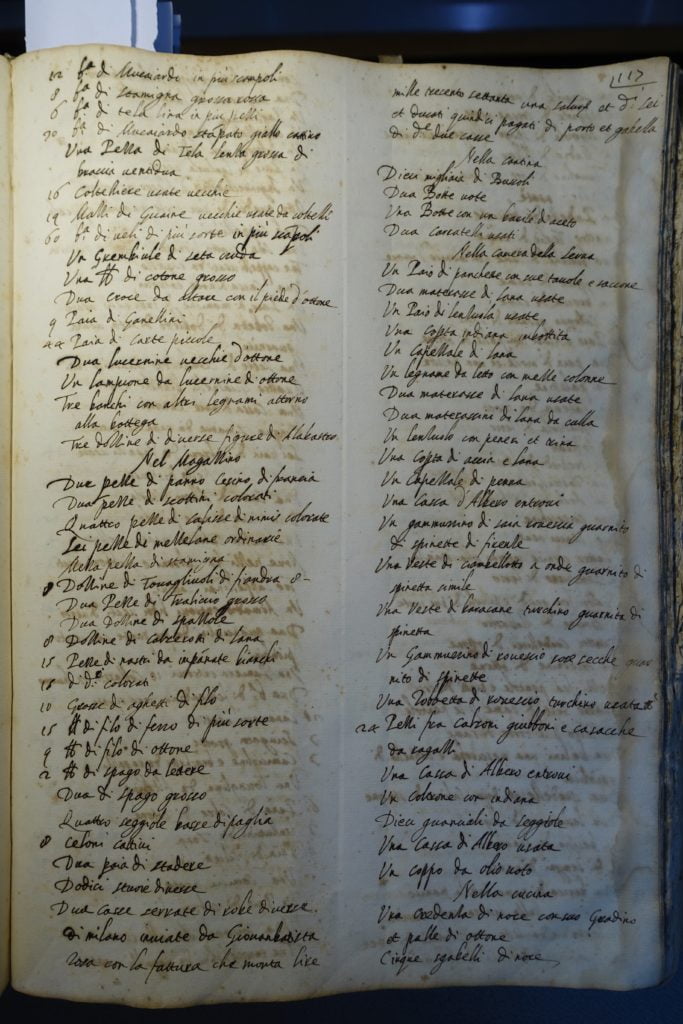

These fashionable accessories would have been costly to have made and to maintain; they required many metres of fine linen and lace, and in order to be worn, had to be carefully cleaned, starched, set and pinned in place by a professional. Large collars and cuffs also impeded the wearer’s movement and posture – imagine trying to eat or write, let alone work while wearing frilly cuffs and a collar! For these reasons, scholars usually assume that ruffled collars and cuffs were worn just by the very wealthy, who didn’t have to engage in physical labour to support themselves or their families. But contemporary descriptions of peasants, artisans and other working people sometimes note that they had ruffles on their collars and cuffs; painted and printed images show these same people wearing decorative and unnecessary accessories at their necks and wrists; and household inventories locate these items in the chests and cases that contained their wardrobes.

For example, in his costume book, Habiti antichi et moderni di tutto il mondo (Venice, 1598), Cesare Vecellio describes artisan and common women in Rome as, ‘ornamenting their necks with strings of coral with some gems and with some little ruffles on their very white shirts.’[1] These ruffles line the open neckline of the woman’s shirt and also peek out at her wrists in the image that accompanies Vecellio’s text.

Figure 4. Artisan woman of Rome from Cesare Vecellio Habiti antichi et moderni di tutto il mondo (Venice, 1598), 23v.

This woman’s clothing, which looks heavy and somewhat cumbersome, does not suggest she is heading to work; however, other images show people at work whilst wearing decorative collars. Vincenzo Campi’s painting of a fruit-seller, for instance, shows a woman in a white, loose-fitting white shirt with neatly ruffled collar open at the front and laying almost flat on her shoulders.

Figure 5. Vincenzo Campi, The Fruit Seller, c. 1580. Oil on canvas, 145 x 215 cm. Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan.

Another scene by Campi shows women at work in more strenuous roles, wearing shirts with collars in a range of styles, as well as other accessories for their necks and shoulders. For instance, the two women rolling out pastry at the table wear shirts with ruffled collars (or perhaps these were separate items attached to their shirts), one is closed, creating a frame for the woman’s face. The other woman’s collar is open at the front and shaped quite similar to that worn by the fruit-seller. Just by opening their collars these women could create quite different looks. In contrast, the women in the foreground wear collarless-shirts with rather low necklines and transparent shawls tucked into the front of their bodices. The older woman working at the mortar and pestle as well as the men and boys in the scene all wear quite simple collars, which fold over the necklines of their outer garments.

Figure 6. Vincenzo Campi, Kitchen Scene, c. 1590-91. Oil on canvas, 145 x 220. Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan.

These are not straightforward representations of people at work; however, inventories suggest that fruit-sellers, butchers and others had shirts and collars like those in Campi’s paintings. For example, a Venetian fruit-seller called Piero owned ‘one new shirt with ruffles’ in 1584.[2] Bernardo Morelli, another Venetian fruit-seller working in the city in 1650 owned ‘seven collars for the neck’.[3]

These simple but decorative additions to shirts might have been suitable for wear during work, but artisans and their family members also had ornate collars and cuffs that would be at risk while performing the tasks in Campi’s painting, such as butchering an animal or rolling out pastry. These fashionable items were probably saved for special occasions rather than work. For example, Cesare Carli, a butcher in Siena had in his home ‘two large ruffs for girls’ in 1638, perhaps worn by his daughters.[4] Another butcher, this time from Florence also owned ruffs, one of fine linen that was not yet sewn and five others that are described as ‘used’ in 1570.[5] These were perhaps similar to the tall, starched collar depicted in Figure 7, dated to around 1620. Although this portrait shows a man of a higher social status than the butchers, his image offers a clear example of one way that large, starched ruffs and cuffs without lace or embroidery could be worn.

Figure 7. Unknown painter, Portrait of a Gentleman, c. 1620. Oil on canvas. Accademia Carrara, Bergamo.

Finally, Giovanni Suster, a Venetian inn-keeper had two collars that featured Flemish lace, one with a set of matching cuffs in 1646.[6] These would have been impressive and fashionable additions to an outfit, though it is difficult to know how large the lace trim was or what kinds of patterns it featured. Perhaps these items were in a style similar to those worn by Maria Maddalena, Cosimo or Ferdinando, discussed above. It is also possible that the lace, which was quite expensive, was a smaller trim along the edge of a linen ruff, as seen in Bartolomeo Passarotti’s painting of man playing a lute. Here, the lace is just a small detail along the edge of the man’s cuffs and collar.

Figure 8. Bartolomeo Passarotti, Man Playing a Lute, 1576. Oil on canvas, 77 x 60 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

These examples and sources show that there were a huge range of options for how collars, cuffs and shirts could be decorated and worn. For artisans and their family members, these kinds of ornate and decorative items offered a means through which they could make individual choices and dress fashionably.

Further reading:

Janet Arnold, Jenny Tiramani and Santina M. Levey, Patterns of Fashion 4: The Cut and Construction of Linen Shirts, Smocks, Neckwear, Headwear and Accessories for Men and Women c.1540-1660 (London: Macmillan, 2008).

Natasha Korda, ‘Accessorizing the stage: Alien Women’s Work and the Fabric of Early Modern Material Culture’, in Ornamentalism: The Art of Renaissance Accessories, ed. by Bella Mirabella (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011), pp. 223–52

Georges Vigarello, Concepts of Cleanliness: Changing Attitudes in France since the Middle Ages, trans. Jean Birrell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), pp. 41-89.

Amanda Wunder, ‘Innovation and Tradition at the Court of Philip IV of Spain (1621-1665): The Invention of the Golilla and the Guardainfante’, in Fashioning the Early Modern: Dress, Textiles, and Innovation in Europe, 1500-1800, ed. by Evelyn S. Welch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 111–33

[1] Cesare Vecellio, Habiti antichi, et moderni di tutto il mondo (Venice: Sessa, 1598), 24r.

[2] Archivio di Stato di Venezia (hereafter ASV), Giudice di Petizion, Inventari, b. 338, f. 66, 14 November 1584, 1v.

[3] ASV, Giudice di Petizion, Inventari, b. 363, f. 18, 26 April 1650, 2r.

[4] Archivio di Stato di Siena, Curia del Placito, b. 280, f. 83, 5 January 1638, 105r.

[5] Archivio di Stato di Firenze, Magistrato dei pupilli, b. 2709, 20 September 1570, 19r.

[6] ASV, Giudice di Petizion, Inventari, b. 360, f. 25, 11 Septemeber 1646, 9v and 10v.