An inn-keeper’s inventory and inspiration

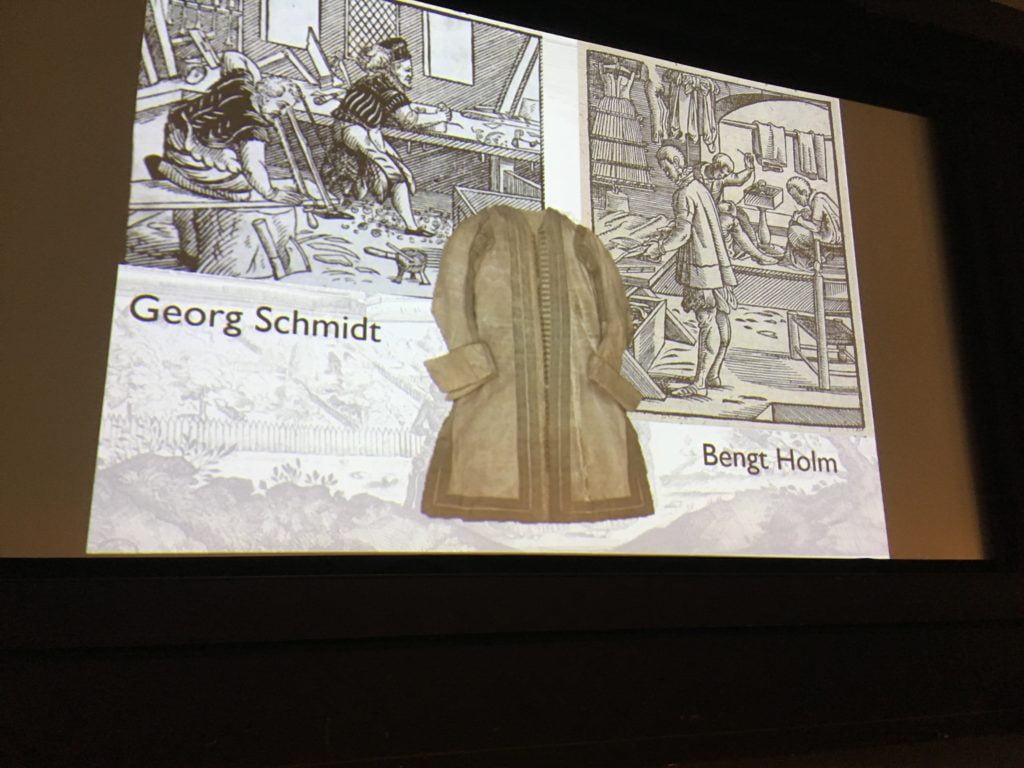

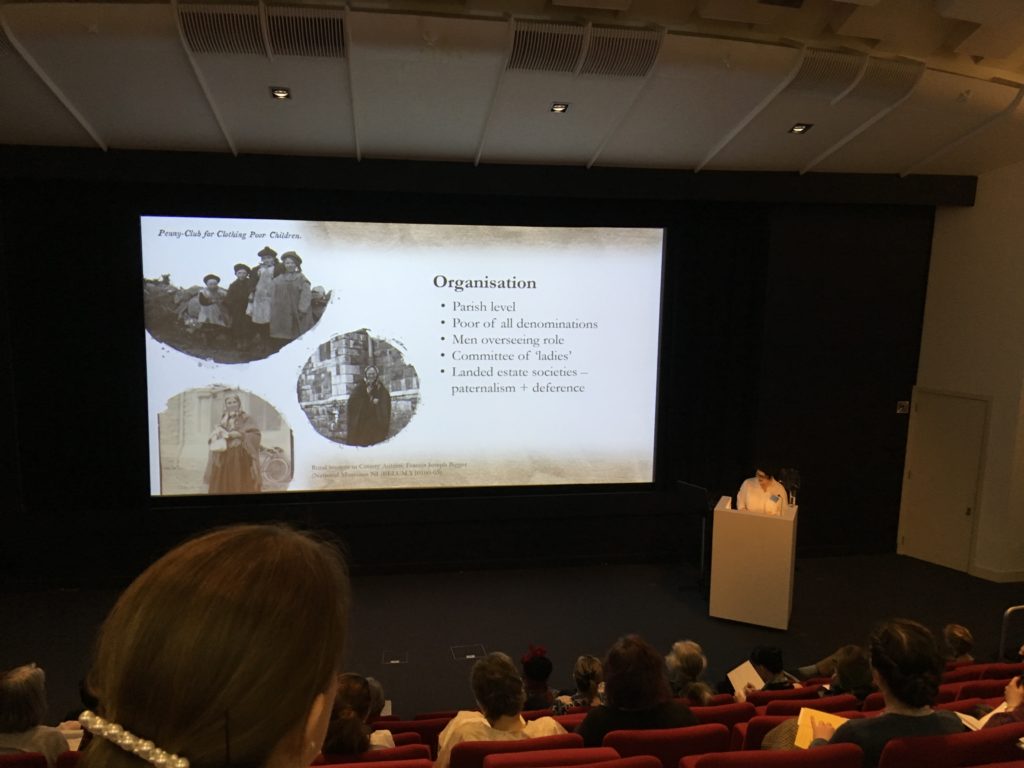

Inventories are key to providing us with insight into the clothing that people had in their homes or in shops like those of tailors and second-hand-clothing vendors. Thanks to Stefania’s hard work gathering, transcribing and categorising these documents for the project’s database, we have a huge amount of data that can be used to try and trace trends in consumption, like the kinds of colours or fabrics that were popular at various times and in different cities. But the inventories can also support more focused research and help us develop case-studies, as they sometimes provide a great deal of information about families and individuals. This in turn helps us to develop a fuller picture of how clothing may have been linked to different aspects of identity, for instance profession, marital status, wealth, age or the neighbourhood in which people lived or worked.

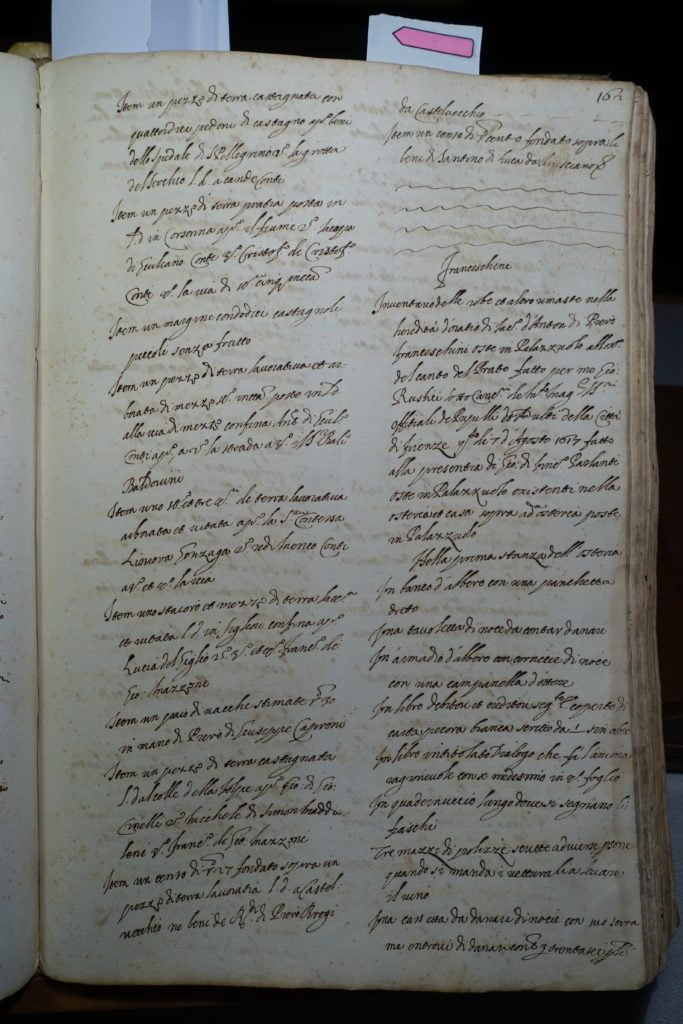

The first page of the inventory of Oratio Franceschini’s home and inn. Archivio di Stato di Firenze, Magistrato dei pupilli, busta 2717, 7 August 1617, 162r–165v.

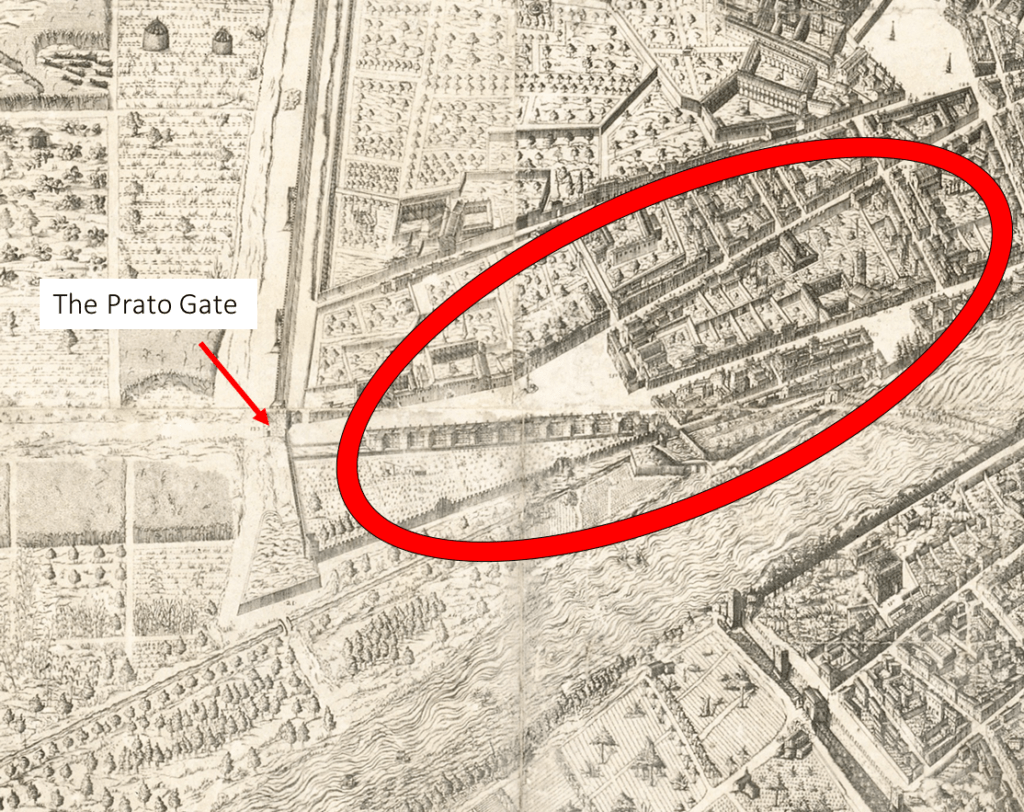

For instance, Oratio Franceschini was an inn-keeper in Florence until his death in 1617, when an inventory was drawn up of his inn and home. The document tells us that the inn where he worked and lived with his wife, Silvia, and their underaged children was located on the corner of via il Prato and via Palazzuolo. The approximate location of the inn is shown circled in red in the image below. After Oratio’s death, the ownership of the building was split between his brother, Zanobi and Madonna Olivia, who was his paternal aunt and the wife of Giovanni Parlanti, also an inn-keeper and present at the time the inventory was compiled. There are several points in the inventory where Giovanni interjects to give details on entries, such as the names of owners of things that had been pawned to Oratio or which pieces of clothing belonged to Silvia.

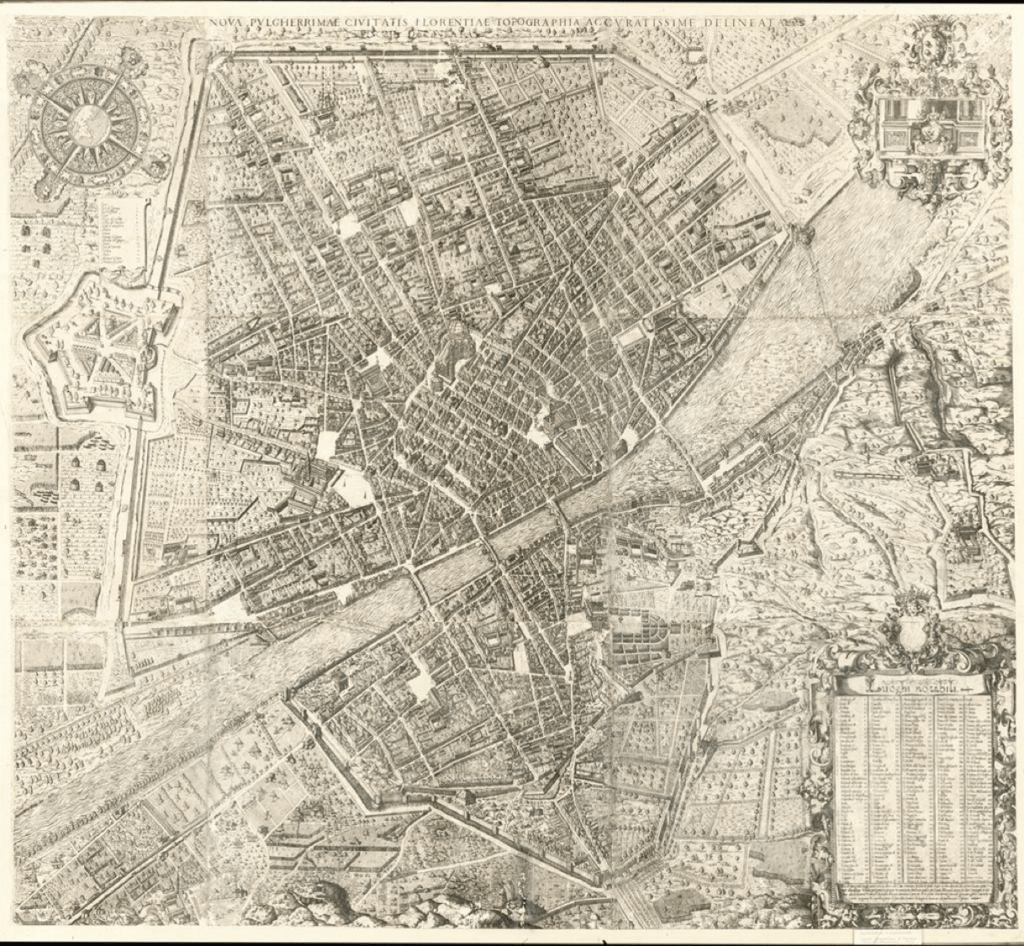

A map of Florence in the late-sixteenth century. Stefano Buonsignori, Nova pulcherrimae civitatis Florentiae topographia accuratissime delineate, 1594. Museo “Firenze com’era”, Florence.

A detail of Buonsignori’s map showing the approximate location of Oratio Franceschini’s inn and home.

Indeed, there are many, many garments listed in this inventory, aspects of which dovetail with the interests of different members of the project, offering points of departure for further research. For instance, three of Oratio’s shirts as well as a number of sheets and napkins are noted as having been ‘in the wash’ when the inventory was made, and there are tubs for laundry listed in the inn’s kitchen suggesting some of this work – washing clothing and linens – was done at the inn.

Ippolito Scarsella’spainting showing the laundering of linens outside of an inn. Ippolito Scarsella, Supper at Emmaus, c. 1600. Oil on canvas, 99 x 124cm. Private Collection. Image courtesy of Fondazione Federico Zeri, University of Bologna.

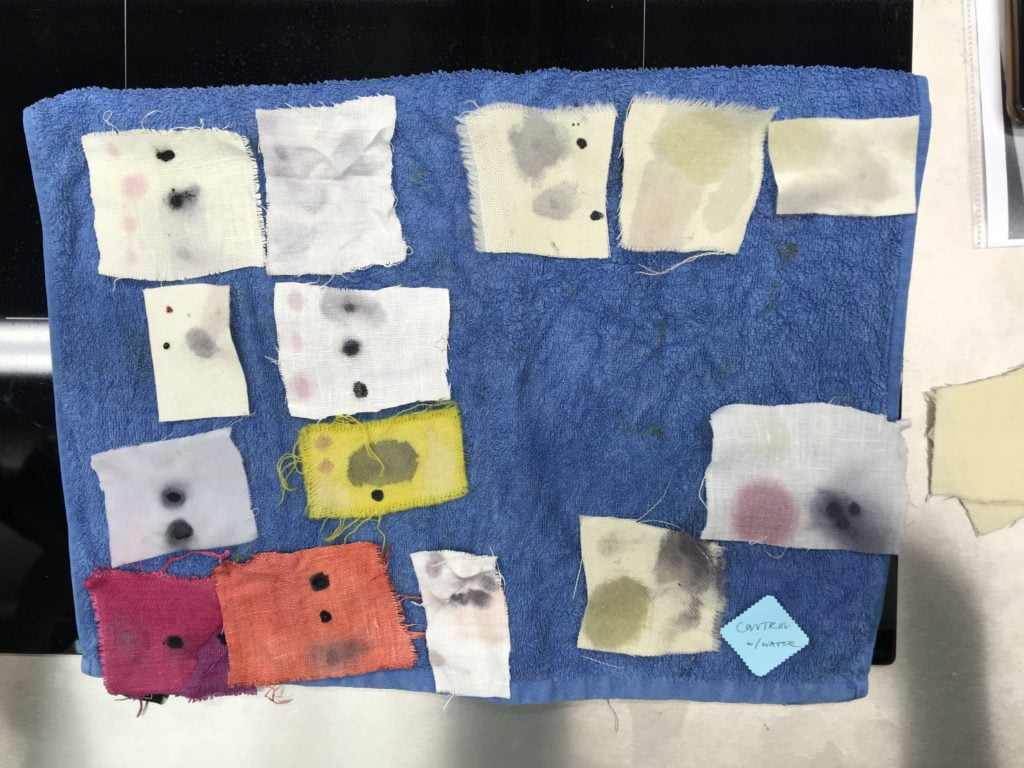

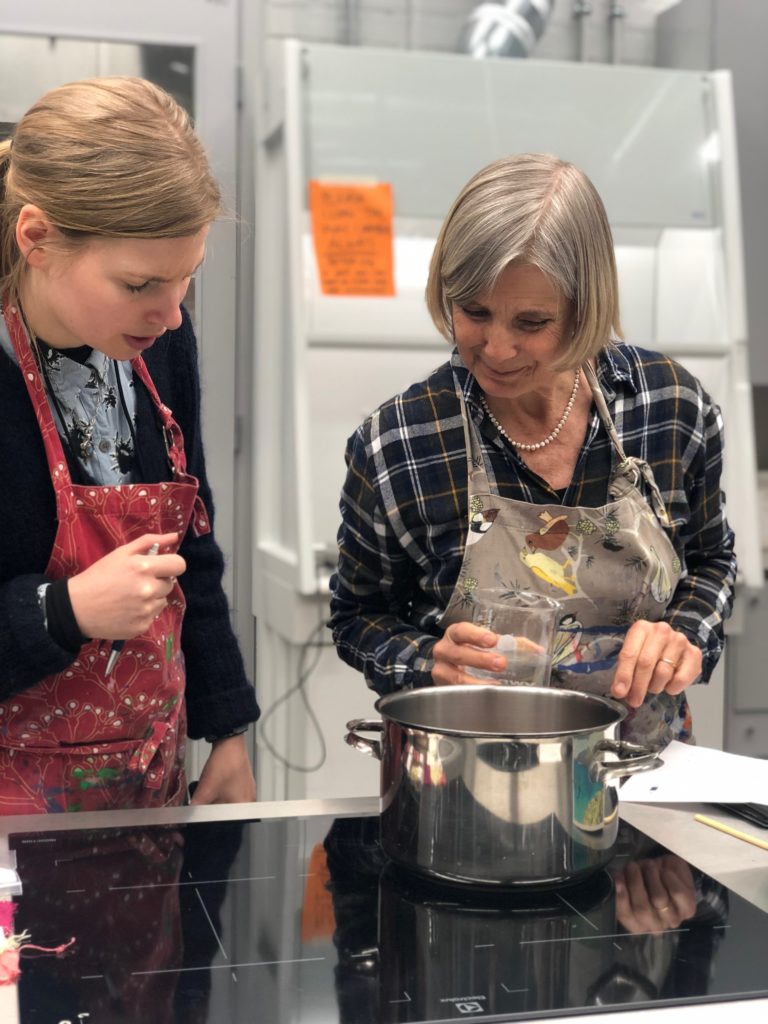

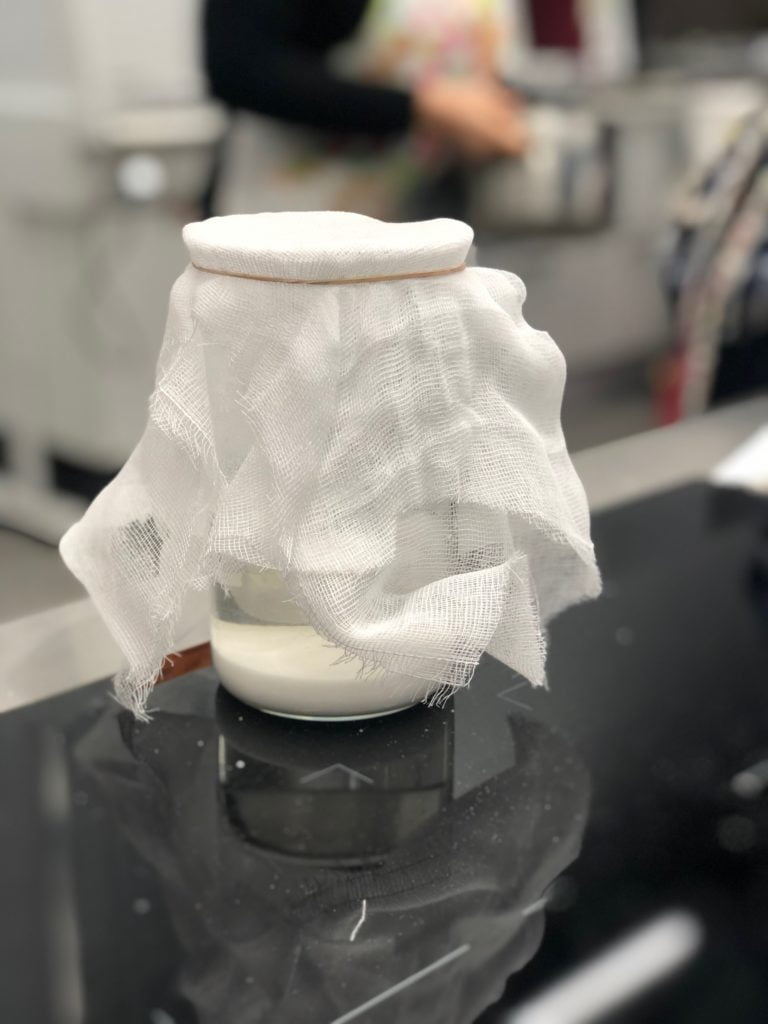

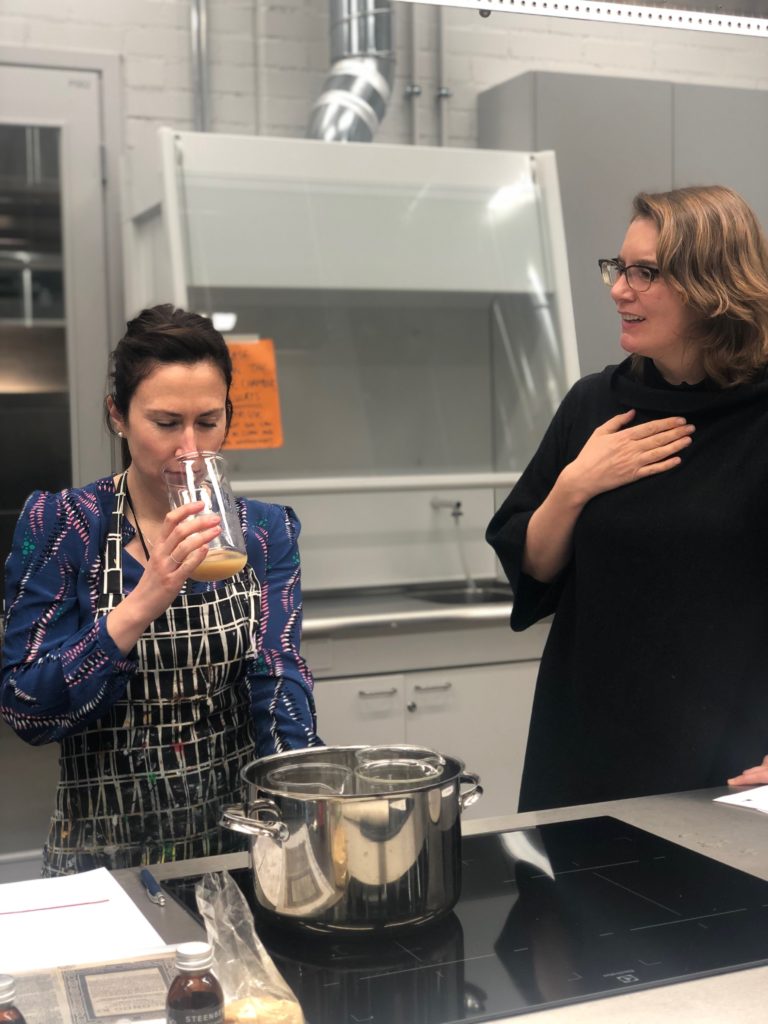

This is really useful evidence for my research on caring for clothing in this period, part of what our experiments with recipes meant to support in April. We don’t know very much about the laundering of clothes in this period, but that it was usually done by women, who were sometimes hired by other households to wash their linens. These could be washed in a mix of hot water and lye at home, if one had the necessary tools (like Silvia, the inn-keeper’s wife), but it was hard work, carrying loads of wet laundry to a riverbed or well to beat and rinse the items with the water. Women also had to protect the clothing against thieves as it hung to dry, and protect themselves from the unsavoury characters that sometimes lurked about riverbeds. This, and that some laundresses were reformed prostitutes, gave the work negative connotations and meant that it was very important for the women that did this work to be careful in order to stay safe and keep their reputations—and those of their families—intact.

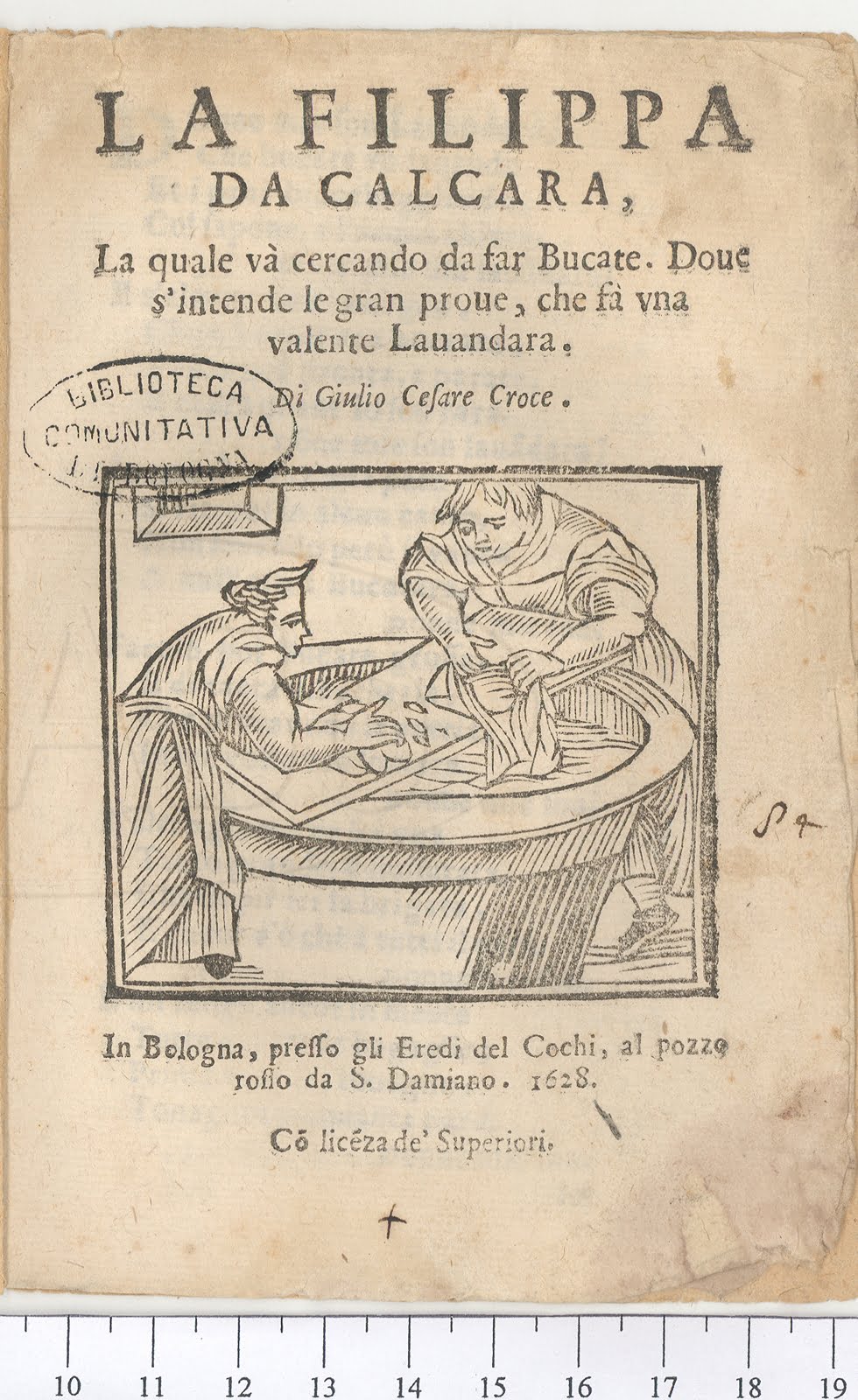

The title page of a poem by the Bolognese poet and songwriter Giulio Cesare Croce, about a laundress in search of clients with clothes for her to wash. Giulio Cesare Croce, La Filippa da Calcara (Bologna: gli eredi di Cochi, 1628).

Keeping linens clean was important for good hygiene but also for social and cultural reasons; for instance, in the early modern period, having bright white linens became a sign of civility, politeness and purity. Laundry was especially important at an establishment like an inn, as both beds and food and drink were provided to guests, meaning bedding, tablecloths and napkins would have been dirtied quickly and frequently. A common complaint about contemporary inns was that they were unclean; for instance, in his description of all the professions found in Venice, Tommaso Garzoni notes in his La piazza universale (1605) how typical it was for inns to have ragged towels, sheets in pieces, cushions that stink of urine and bolsters full of bedbugs (711–2)! To combat this kind of stereotype, it may have been even more important that inn-keepers ensure linens were clean and, as mentioned above, there were tablecloths and napkins in the wash with Oratio’s shirts.

In this period there were many negative ideas about inns and inn-keepers; this moralising engraving shows the debauchery of a local inn with the inscription: “The nuzzle of dogs, the love of whores, the hospitality of inn-keepers: None of it comes without cost.” Gillis van Breen, Inn Scene with Prostitutes, 1597. Engraving, 133 x 194 mm. Prentenkabinet, Universiteit, Leiden.

Evidence in the inventory of Oratio’s home and workplace suggest efforts to keep clothing and linens clean; however, there is also evidence of garments that were in rough shape. The document describes many shirts, hose, cloaks, skirts and doublets as ‘nasty’, and to a lesser degree, ‘broken’ and ‘ragged’. Garments like these, like those ‘in the wash’, are also useful pieces of evidence for my research on how people cared for their clothing and in particular, the very long life-span of garments. ‘Nasty’ and ‘ragged’ clothes remind us that in the past, people did not just get rid of items that were no longer in pristine condition or in the latest style. Instead, these were re-dyed, mended, re-used and worn until they could be worn no more. This is part of why we have so few extant garments from this period, when people rarely threw out clothing and instead sold it off, transformed it into something new, or wore it to rags and then sold those rags on to be made into paper.

These underpants found under the floor of an Austrian castle show signs they were repaired at least three times! Perhaps we should take a lesson from our ancestors? Underpants from Lengberg Castle, Nikolsdorf. Fifteenth-century. Linen. Nikolsdorf, East Tyrol, Austria; Lengberg Castle.

Although much later than this inventory, Gaetano Zompini’s engraving shows a female second-hand clothes dealer at work. Gaetano Zompini, ‘Revendigola (Secondhand Clothes Dealer)’, plate 39 in Le Arti che vanno per via nella Città di Venezia(1785). Engraving and etching on laid paper; plate: 26.7 x 18.3 cm (10 1/2 x 7 3/16 in.).

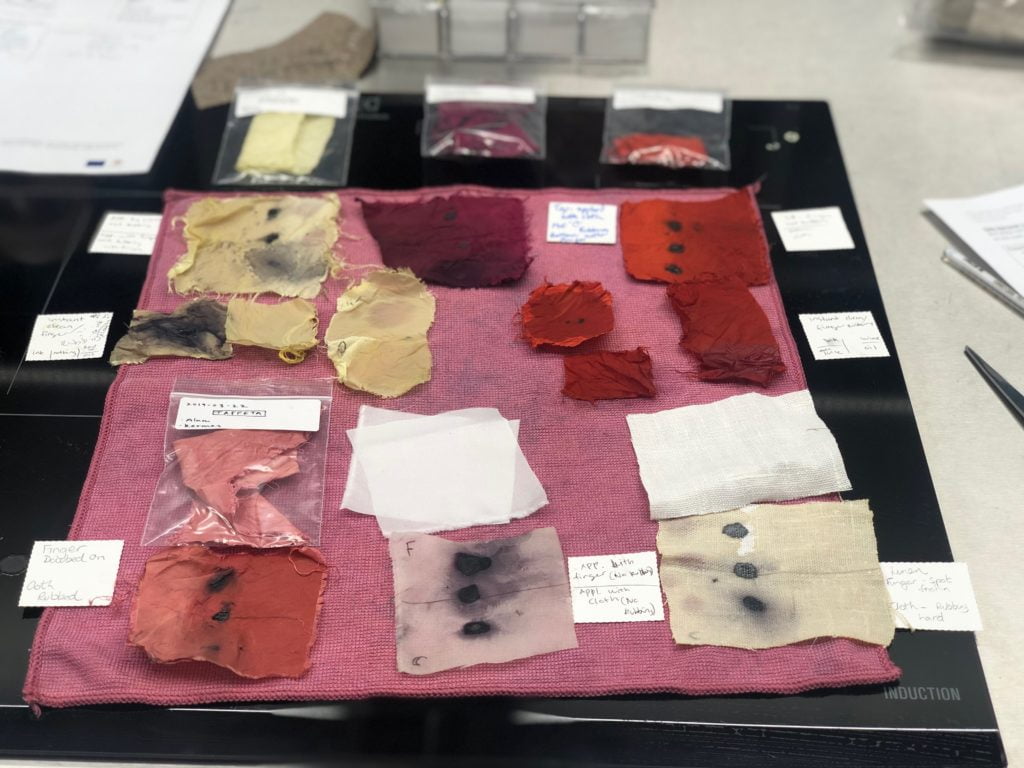

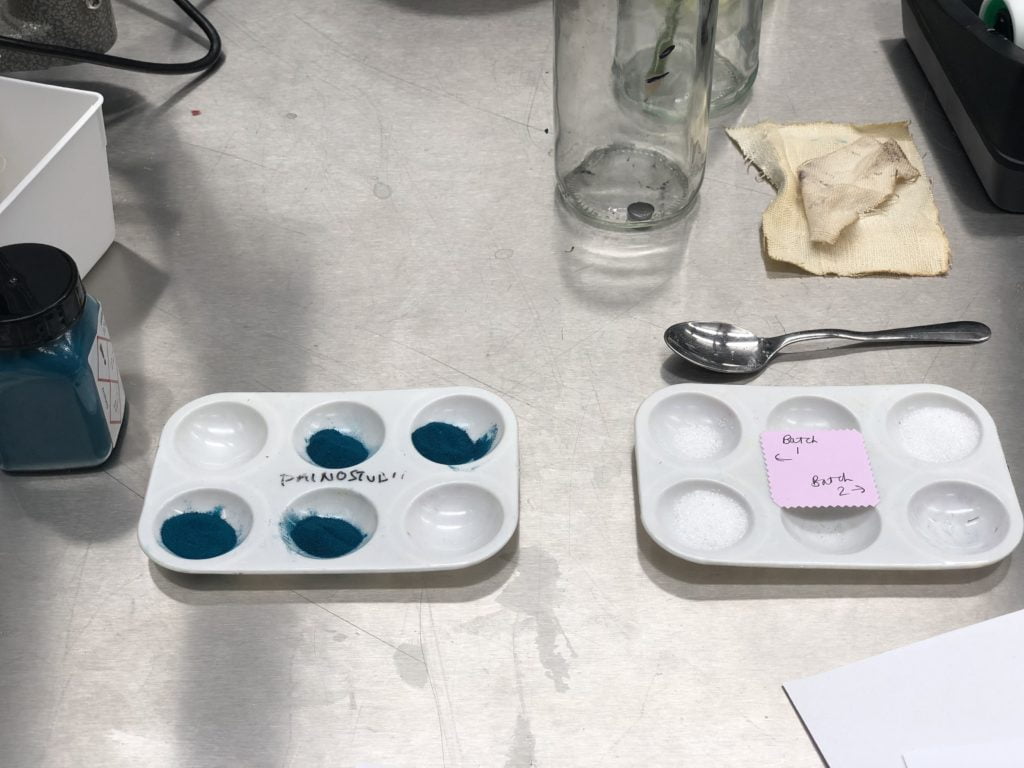

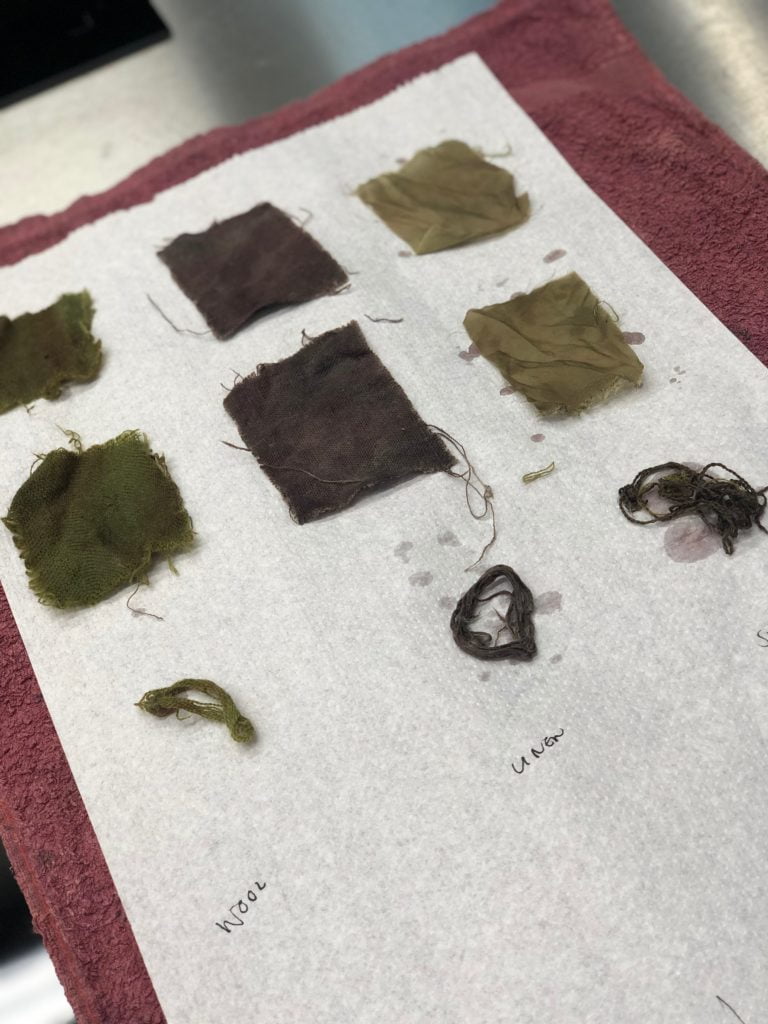

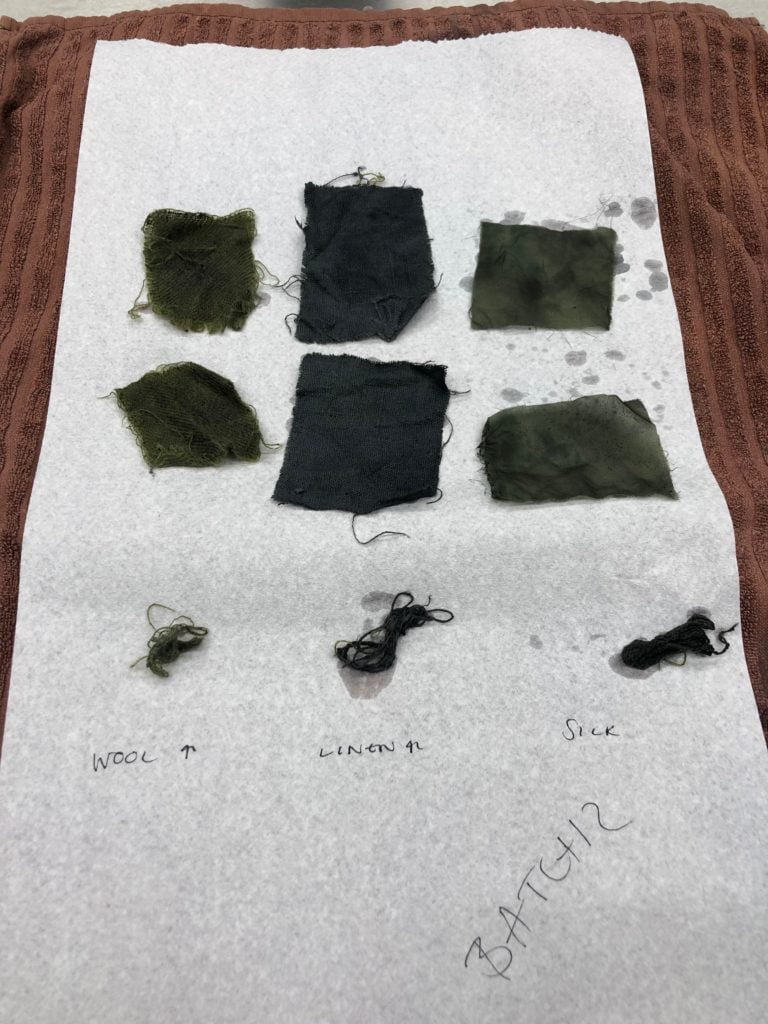

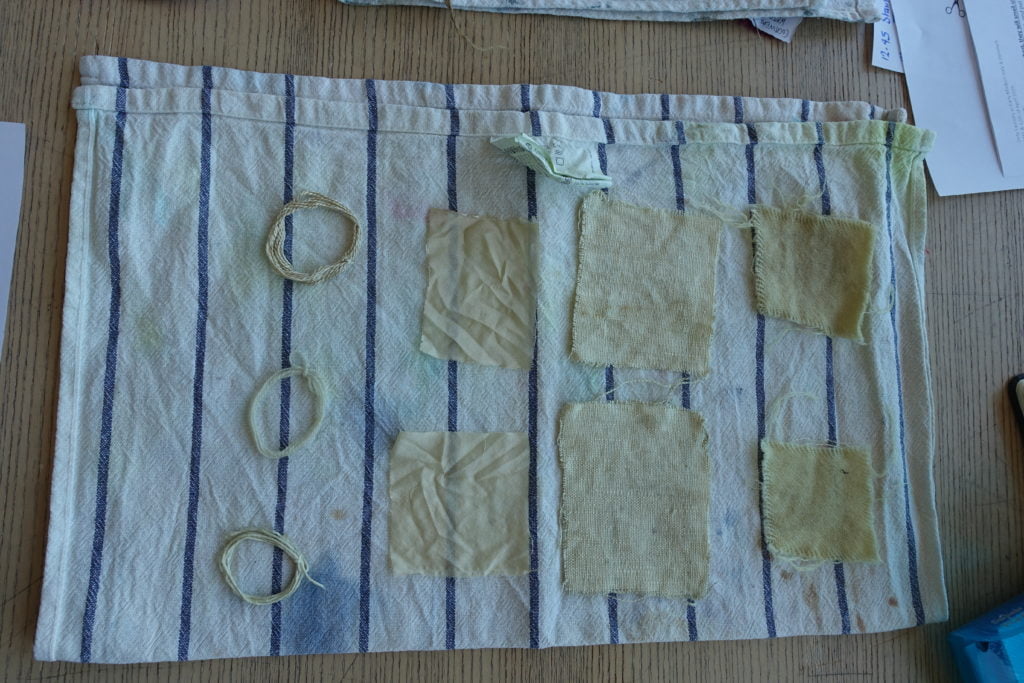

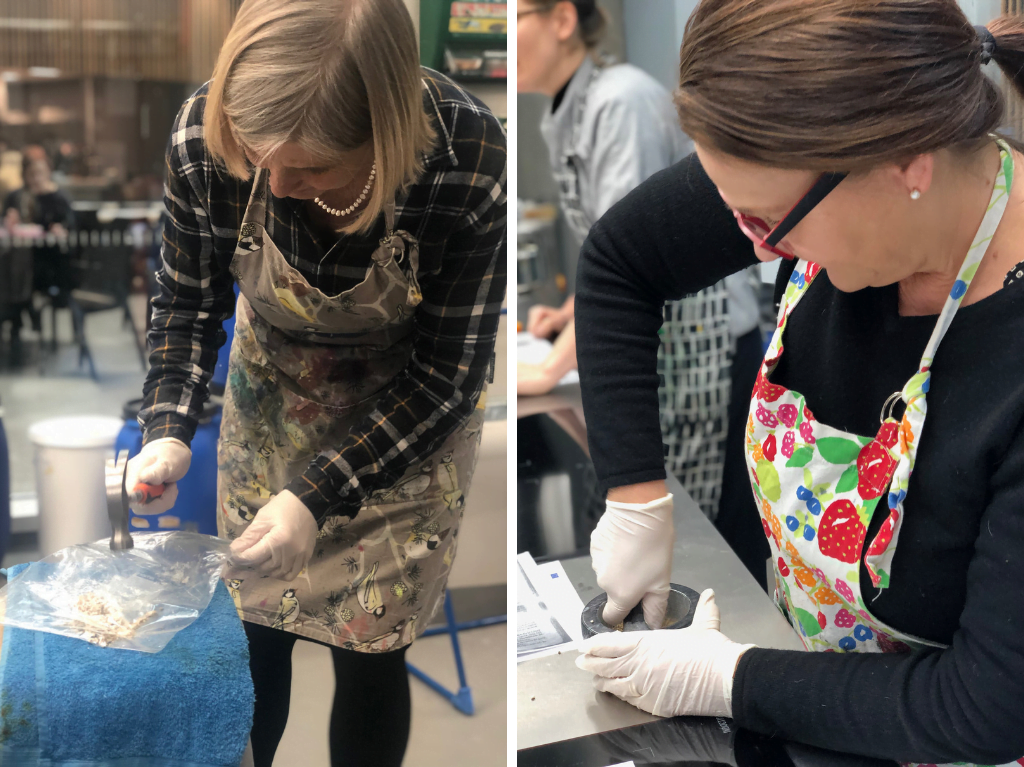

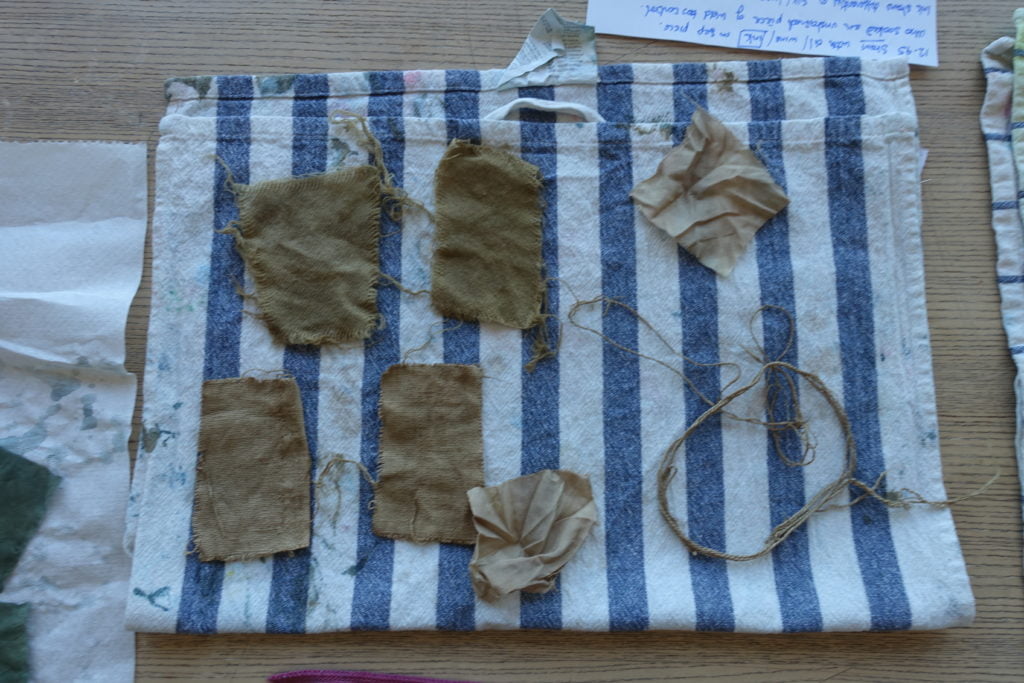

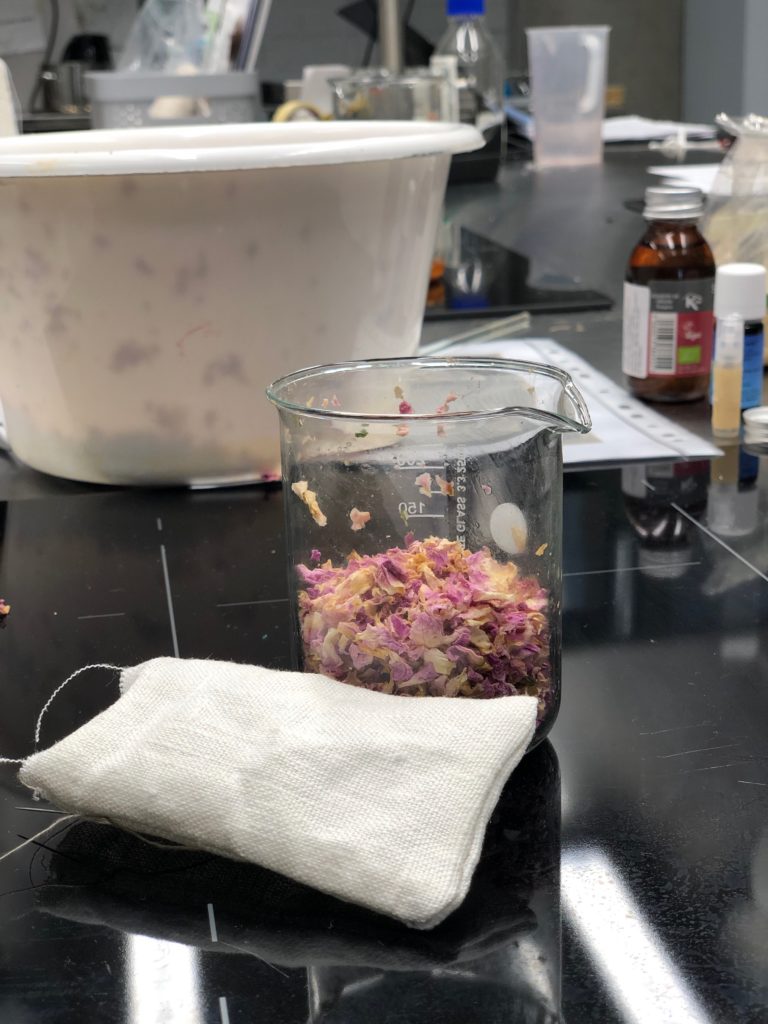

The inn-keeper’s inventory shows that the family had clothes in the wash and garments in rags, but also some pieces that sound rich and colourful. For example, Silvia had several head-coverings that were trimmed with gold and silver and a muff made of fur. The inventory also describes an over-gown the colour of sea water, a bodice of lavender and a shirt the colour of dried roses. We also find sleeves of silk, a black satin bag and a doublet of light wool. Some of these fabrics, garment-types and colours don’t survive today, and we must turn to contemporary images and other texts to try and understand what they looked like. We can also try to recreate these textures, colours and objects through experiments, as with the project’s colour workshop in September 2019 and the doublet that Sophie is working to recreate. It will be really exciting to see our results!

This small image from a printed game shows in interior of an inn with an inn-keeper, seller of wine and a serving woman. Similar to inventories, it offers some detail about their clothing but not the colour! Detail from Giuseppe Maria Mitelli, Gioco de mestieri a chi va bene e a chi va male, 1698. Etching, 326x438mm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Inventories like that of Oratio Franceschini’s home and workplace can help shed light on the wide variety of clothes that regular sorts of people had – those in the wash, ragged or beautifully coloured. They sometimes offer vivid descriptions and points from which we can investigate further using contemporary texts, poems, images and other archival documents. We can also use experiments to try to recreate fabrics, perfumes, colours and finishing techniques to bring back to life and refashion what is now lost.

Representations of the Supper at Emmaus were popular in the early modern period and give us a glimpse of what might have been worn by contemporary inn-keepers, like the one here with a cap, white ruffled collar, brown jerkin, doublet with red sleeves and a white shirt with sleeves rolled up. Paring these kinds of images with inventories and other sources can help us determine how truthful they are. Caravaggio, Supper at Emmaus, 1601. Oil on canvas, 141 x 196 cm. National Gallery, London.

For further reading:

On inn-keepers and their homes/work places:

- Paula Hohti, “The Innkeeper’s Goods: The Use and Acquisition of Household Property in Sixteenth-Century Siena,” in The Material Renaissance, ed. Michelle O’Malley and Evelyn S. Welch, Studies in Design (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010), 242–59.

On laundry, hygiene and washer women:

- Katherine F. Rinne, “The Landscape of Laundry in Late Cinquecento Rome,” Studies in the Decorative Arts9, no. 1 (2001): 34–60.

- Guido Guerzoni, “Servicing the Casa,” in At Home in Renaissance Italy, ed. Marta Ajmar-Wollheim and Flora Dennis (London: V&A Publications, 2006), 146–51.

- Douglas Biow, The Culture of Cleanliness in Renaissance Italy(Ithaca ; London: Cornell University Press, 2006).

- Sandra Cavallo and Tessa Storey, Healthy Living in Late Renaissance Italy(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), especially chapter 8, ‘Excretions as Excrements: The Hygiene of the Body’, pp. 240-239.

On the second-hand market and the pawning of clothes in early modern Italy:

- Patricia Allerston, “Reconstructing the Second-Hand Clothes Trade in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Venice,” Costume 33, no. 1 (January 1, 1999): 46–56.

- Giulia Calvi, “Abito, Genere, Cittadinanza Nella Toscana Moderna (Secoli XVI-XVII),” Quaderni Storici 110 (2002): 477–503.

- Isabella Cecchini, “A World of Small Objects: Probate Inventories, Pawns, and Domestic Life in Early Modern Venice,” Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme 35, no. 3 (2012): 39–61.

- Maria Giuseppina Muzzarelli, “From the Closet to the Wallet: Pawning Clothes in Renaissance Italy,” Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme 35, no. 3 (2012): 23–38.

- Carole Collier Frick, “The Florentine ‘Rigattieri’: Second Hand Clothing Dealers and the Circulation of Goods in the Renaissance,” in Old Clothes, New Looks, ed. Alexandra Palmer and Hazel Clark, Dress, Body, Culture (Berg Publishers, 2004), 13–28.