Make invisible, visible. News from Venice’s Archive

Studying material culture for those social groups that weren’t part of the elite has always proven difficult. Lesser documents were indeed produced by artisans, workers and poor people, even in societies, as the “Italian” ones, that historically proved to be particularly inclined to the use of notaries and courts to certify relationships and exchanges.

How can we spread the light on the standard of living of working classes then?

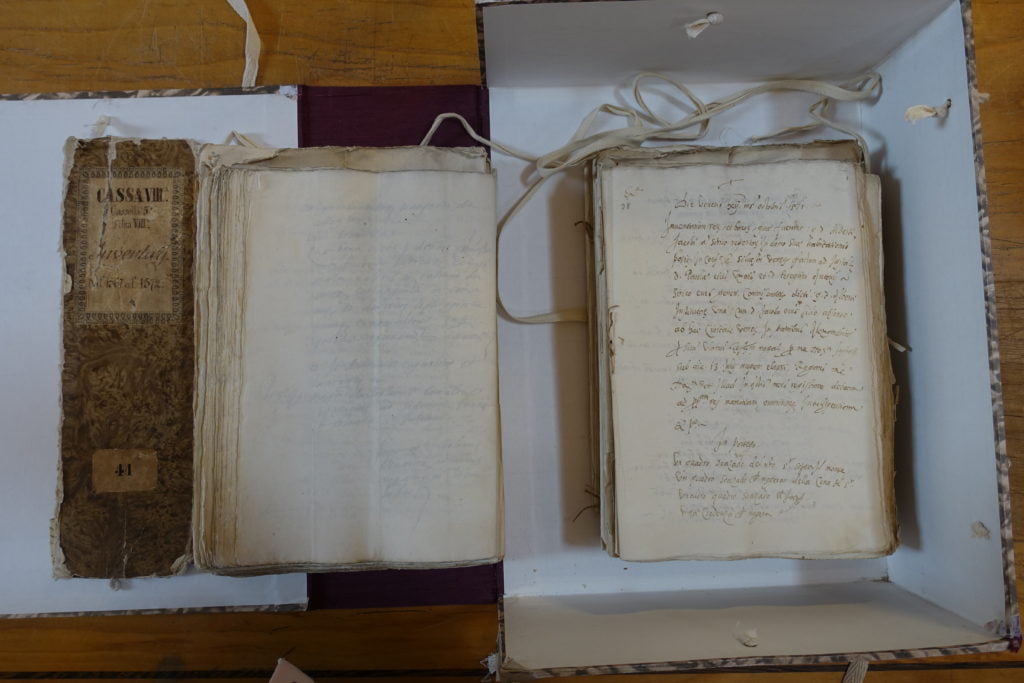

One of the most important sources in order to make invisible people a bit more visible are probate inventories. These documents were usually a list, more or less precise, of the possession of a person at a certain moment of their life.

Archivio di Stato di Venezia.

But why someone would feel the need to write an inventory? Well, the reasons are different, since inventories had different purposes.

Firstly, they were the main tool to estimate an inheritance. When a person died, no matter how rich they were, the heirs or their guardians (called commissari) asked to list all the items that could be inherited, as well as to evaluate them. This process could involve several people, from the notary who registered the documents (testaments and inventories) to the person charged to estimate the value (usually a haberdasher or another artisan). These inventories show all the objects that these people were able to accumulate in their life and, often, also those of their entire family, giving us the possibility to understand how consumption evolved within specific social classes.

Secondly, an inventory could be asked from creditors. In these cases, a court was usually involved and the inventory listed all the objects that were present in a home or, more often, in a workshop, that could be used to refund the petitioner.

Lastly, inventories could be written to certify a dowry. Young women were granted a certain amount by their father when getting married, that could be paid in money, objects or estate properties (an amount that scholars more recently started to identify as an anticipation of the inheritance). Even if this dowry was usually managed by the groom’s family, once the husband would eventually die, women had the right to get it back. In order to refund the widow of her dowry (that she could finally start managing herself), an inventory was usually requested by a court, in order to identify the suitable objects to be returned.

Probate records from Venice.

These documents of course don’t just show us a list of possession. Inventories present indeed not only the precise origin or position of houses and workshops, but also the names of the commissari appointed by the deceased. Inventories will tell us not only what these artisans were wearing, using and accumulating, but also will give us a glimpse into the social world of these people.

In the future we will share more detailed glimpses into these interesting documents.