Defence, Honour, and Dress

By Victoria Bartels

In early modern Europe, one could argue that all types of dress and apparel offered protection. Clothing acted as a barrier between the physical body and the outside world, shielding it from over exposure and external threats. The link between protection and fashion was most pronounced, however, in the Renaissance male wardrobe. Men’s dress often included literal objects of defence, such as swords, daggers, and protective garments. Notions of masculinity in this period stemmed from medieval chivalric ideals, thus, protecting oneself and one’s household became traits associated with male honour. Violence on the street or in the market, workshop, or tavern were common occurrences in early modern Italian life. Thus, weapons became both fashionable and functional, and were understood as symbols of one’s masculinity.

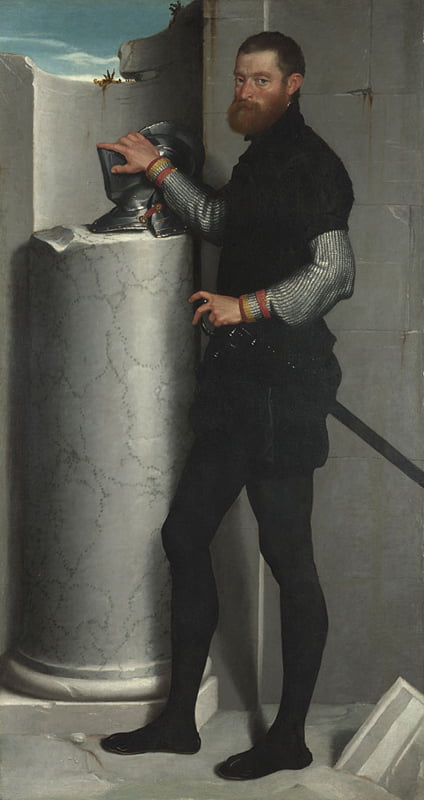

Image 1. Giovanni Battista Moroni, A Knight with his Jousting Helmet (‘Il Cavaliere dal Piede Ferito’, Conte Faustino Avogadro (?)), ca. 1554-58, 202.3 cm x 106.5 cm, National Gallery, London.

Since citizens were legally permitted to carry arms, weapons were considered a crucial part of the upper-class man’s wardrobe. However, the practice of owning arms was not restricted to the elite. Many of the Refashioning inventories collected from Florence, Siena, and Venice include weapons, and the men who owned these items cut across different social classes. We know from the data, for instance, that swords were owned by men working in a variety of occupations. Some examples include a smith, silk merchant, painter, greengrocer, potter, barrel-maker, barber, trumpet-player, and linen weaver. Bladed weapons, such as swords and daggers, were the most common objects owned, but knives, crossbows, pole arms, and firearms were also recorded. Protective clothing was also present in the documents. These were typically garments fashioned from mail armour or sleeveless vests of thick leather worn underneath clothing to protect the body from would-be attackers.

Swords were undoubtedly the most popular weapon owned by men in this period. In his colourful autobiography, the Florentine goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini used the word “sword” a total of seventy-eight times.[1] Documentary sources often describe them quite vaguely, solely listing the word “sword” (spada), but they occasionally also recorded a weapon’s adornments, especially if they were noteworthy or valuable. An example of this can be found in the inventory of a Florentine linen merchant by the name of Filippo di Sforzo Guerrieri, who owned “a half sword with a silver hilt” (una mezza spada con manica d’argento), while an apothecary from Siena possessed “a sword with rather modern finishes” (una spada con finimenti assai moderni).

Although described quite generally, various models of swords existed, thus, affecting how they were worn and used. Early swords from the medieval period possessed double-edged blades, making their primary function to cut and hack.[2] By about 1530, however, most swords worn by civilians were prized for their pointed blades, and although they could still cut, thrusting was considered their primary objective.[3] These “thrusting” swords were lighter to wield than previous bladed weapons and had hilts with bars and loops meant to protect the wearer’s hand.[4] The catch-all term for this type of side sword was the “rapier,” although no standardized form existed until the mid-sixteenth century.[5] Other models of swords were also prevalent in society. For instance, in 1612, a Venetian innkeeper’s inventory boasted “two scimitars in the Turkish style with their [accompanying] large sword belts (due samitere alla turchesca con suoi centuroni).”

Image 2. Venetian, Scimitar, 1550, steel, gold, silver, copper alloy, enamel, Wallace Collection, London.

Coming in a close second to swords, daggers were also widespread in this period. Given their smaller size, daggers were easier to wield than swords and therefore, required less training to use. The dagger derived from the scramasax, a versatile short knife used by the Saxons for a variety of jobs.[6] Like swords, dagger styles evolved over time to accommodate changing needs in battle. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, knights carried daggers with double-edged blades and by the fifteenth century, the typical model was replaced by the rondel dagger, taking its name from the circular pommel adorning its grip.[7] Left-handed daggers for parrying became the go-to short-bladed weapon in the sixteenth century, as the interest in fencing peaked. Other types of short-bladed weapons, such as the stiletto and the notoriously dangerous sfondagiaco, were also popular options.

Image 3. Italian, Parrying Dagger, ca. 1550-75, Steel, gold, brass, wood, Length 40.3 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

As both swords and daggers became more regular fixtures in men’s dress, they were commonly fashioned in sets. Accessories for weapons could also be customized. Sword belts, scabbards, and hilts, along with their fabrics and metal workings could be tailored to complement existing outfits. If a patron had the financial means, they could also adorn their weapons with etchings, precious metals, or even jewels. In 1601, for instance, Medici goldsmith Giacomo Biliverti created a matching set of sword and dagger hilts adorned with 680 diamonds.[8] Even with a more modest income, one could add a touch of luxury, as a Sienese candle maker is recorded to have owned “two swords with silver handles” and “a dagger with a silver handle” in 1595. English moralist Philip Stubbes railed against this new practice in his 1583 Anatomie of Abuses saying

“their Rapiers, Swordes and Daggers, gilte, twise or thrise over the hiltes with good Angell golde, or els argented over with silver…” are “a great shew of pride … an infallible token of vaine glorie, and a grievous offence to God.”[9]

Image 4. An imperial example of a lavish sword. Antonio Piccinino, Rapier of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II, 1550-70, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

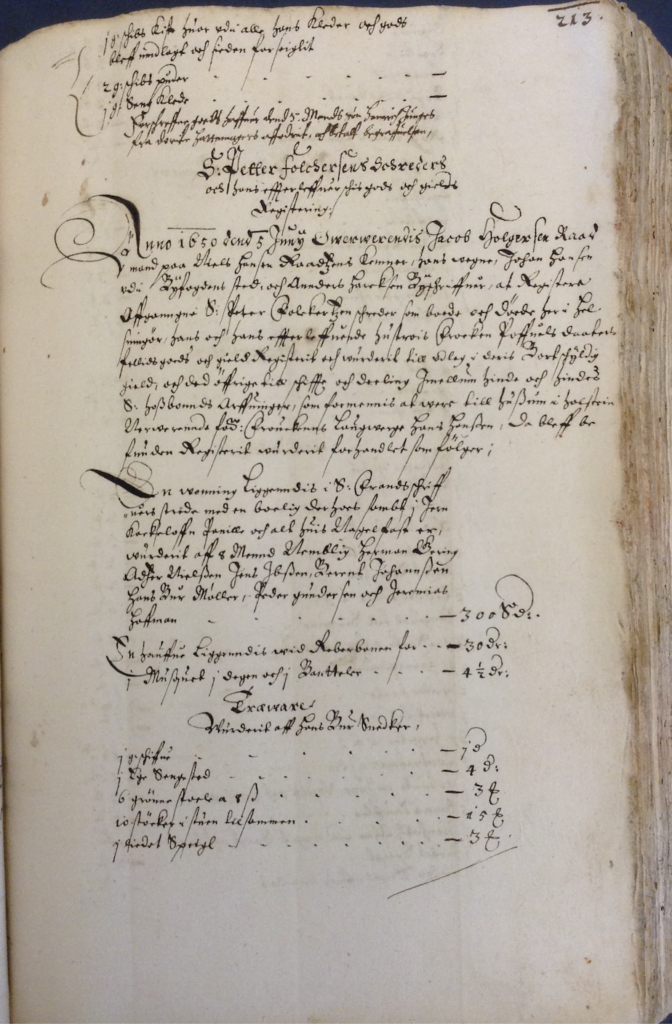

Garments made of mail armour were also present in some of the inventories examined. The Venetian baker Foresto Foresti, for example, pawned a jacket of mail and received a hefty sum of sixty lire in exchange for the garment. A colleague of Foresti working in Venice also pawned a pair of mail sleeves. Mail could be easily hidden under clothing or added to the lining of a jacket or vest. In the 1492 inventory of the Medici guardaroba, for instance, Lorenzo de’ Medici (1449–1492) had several mail garments, as well as a doublet “full of mail.”[10] Having been utilized for centuries, mail was invented toward the end of the Iron Age.[11] Modern efforts to reconstruct mail determined that a typical iron shirt contained anywhere from 28,000–50,000 links, depending on its size and length.[12] As a result of the intricate and time-consuming method of construction, mail garments were often reused and recycled, causing pieces to contain sections of mail from disparate periods.

Image 5. German, Sleeve of Mail, 16th century, Steel, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Image 6. Giovanni Battista Moroni, Portrait of a Gentleman with His Helmet on a Column, ca. 1555-56, Oil on canvas, 186.2 cm x 99.9 cm, National Gallery, London.

As discussed above, male dress practices were heavily influenced by contemporary notions of gender. Although they served as status symbols for upper-class gentlemen, numerous inventories demonstrate that weapons were also sought out by working-class men. By investigating weapons and defensive-wear further, much light can be shed on the social and cultural norms responsible for shaping male fashion in early modern Italy.

[1] Cellini, The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini (Star Publishing, 2012).

[2] Robert Wilkinson-Latham, Phaidon Guide to Antique Weapons and Armour (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1981), 105.

[3] Sydney Anglo, The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2000), 99. Wilkinson-Latham, Phaidon Guide to Antique Weapons, 110.

[4] Wilkinson-Latham, Phaidon Guide to Antique Weapons, 110.

[5] Tobias Capwell and Sydney Anglo, The Noble Art of the Sword: Fashion and Fencing in Renaissance Europe 1520-1630(London: The Wallace Collection, 2012), 33.

[6] Wilkinson-Latham, Phaidon Guide to Antique Weapons, 140.

[7] Wilkinson-Latham, Phaidon Guide to Antique Weapons, 140.

[8] Angus Patterson, Fashion and Armour in Renaissance Europe: Proud Lookes and Brave Attire (London: V&A Pub., 2009), 60.

[9] Philip Stubbes, The Anatomie of Abuses, ed. by Margaret Jane Kidnie (Tempe, Ariz: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies in conjunction with Renaissance English Text Society, 2002), 105.

[10] Timothy McCall, “Brilliant Bodies: Material Culture and the Adornment of Men in North Italy’s Quattrocento Courts,” I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance, 16, no. 1/2 (Fall 2013), 471.

[11] Alan R. Williams, The Knight and the Blast Furnace: A History of the Metallurgy of Armour in the Middle Ages & the Early Modern Period (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 29.

[12] Alan R. Williams, The Knight and the Blast Furnace, 30.