Refashioning the Renaissance Citizen Science Project: Voluntary knitting initiative

Several times over the past two years, students and enthusiastic craftspeople have contacted us, asking how they could be involved in our project. Having thought about this with the rest of our team members, we decided to set up a voluntary knitting initiative. Following my initial enquiries early last Autumn in Facebook, and our official call at the start of this year, we now have about thirty-five voluntary craft experts in our project to create different types of Renaissance stockings for our project, from more simple artisanal ones to the fine and rare seventeenth-century silk stockings that survive in Turku Cathedral Museum.

The project started officially in February 2019. Assisted by the textile conservator Maj Ringaard from the National Museum of Denmark who is an expert in historical knitting, our voluntary knitters first made test samples. We provided them with very fine 0,7mm, 1mm and 2 mm knitting needles, as well as fine wool that resembled the original historical yarn as closely as possible.

Volunteer knitters testing out needles and yarns.

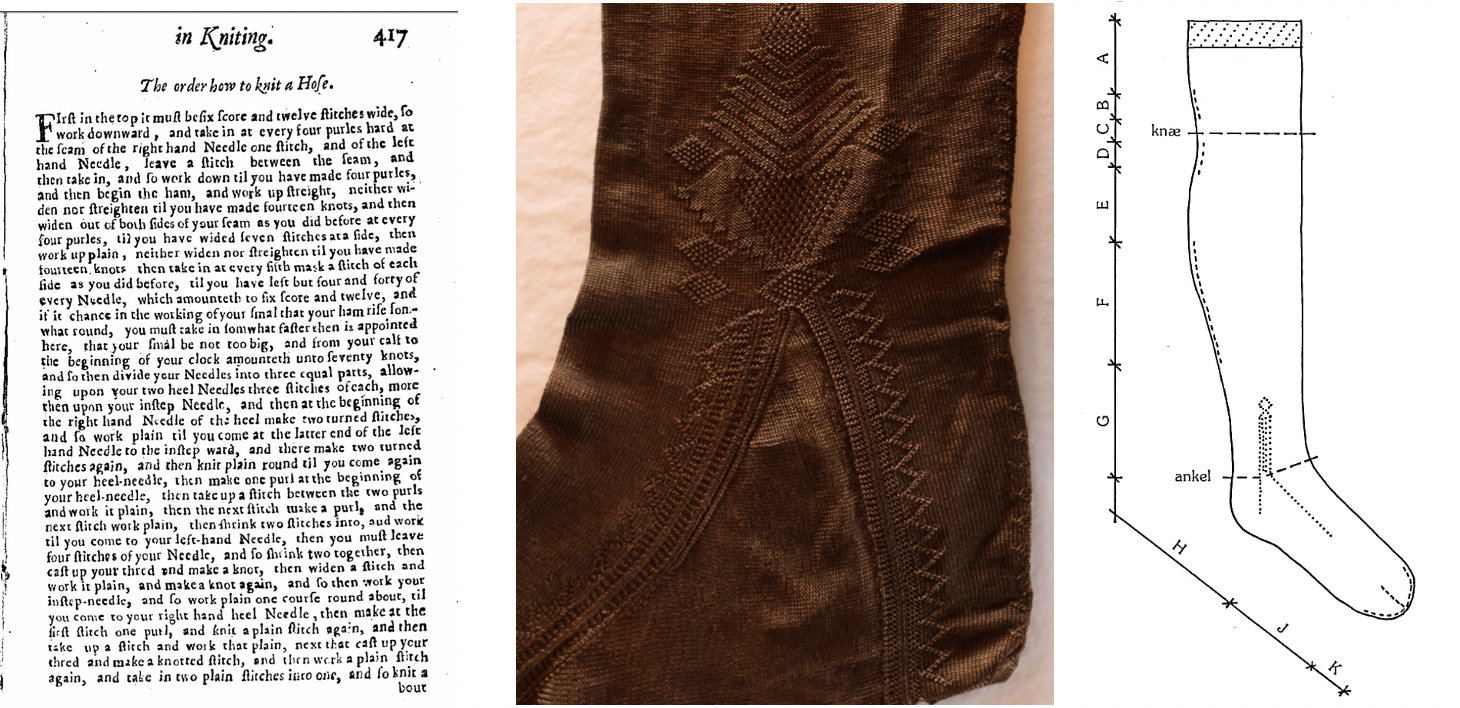

Our volunteers then had to decide what they wanted to start working on, choosing from several alternatives. One option was to reconstruct a coarse and a simpler type of artisanal stocking, based on surviving examples at the National Museum of Denmark; another option was to try to reconstruct a stocking using the first known knitting hose recipe from England in 1655; and the third—and most challenging—option was to reconstruct a fine knitted stocking from Turku Cathedral Museum, either using fine wool or silk.

We are concentrating on three different stocking models in our project. Stocking pattern on the right courtesy of Maj Ringgaard.

It takes quite a lot of skill and patience to knit a Renaissance stocking. What makes this a challenging project is, first, that, as we do not have instuctions for any of the stockings, the group has to come up with the instructions and patterns for the decorations, and then solve the technical issues as they knit the stockings. It is also extremely difficult and time-consuming to knit on 1mm needles, as I discovered myself too during our test session. Another similar knitting project, Silk Stockings from Texel, led by Dr. Chrystel Brandenburgh, carried out at the Textile Research Centre in Leiden, showed that it takes about 200 hours to knit just one fine silk stocking, such as these ones seen below, which I saw in January at the ”Burgundian Black Collaboratory” workshop.

Silk stockings knitted for the Silk Stocking Project led by Dr. Chrystel Brandenburgh.

This type voluntary research initiative is called a Citizen Science Project. The aim of our experiment is not only to reconstruct Renaissance stockings, but we also want to investigate the process, such as, how long does it take to knit a silk stocking or what level of sophistication was needed to produce an artisanal stocking compared to a fine stocking. Therefore, our voluntary knitters are not only experts in knitting, but they also produce important scientific research data of the process of making for our project.

You can follow the progress of the stockings on our website, from on our blog and in the future in our research section!