Historical knitting through citizen science

Knitted stockings were one of the important Renaissance technological innovations. While woollen stockings were widely available across social classes, stockings knitted of fine silk yarn were expensive luxury products and one of the key fashion accessories worn by the European elites from the sixteenth century onwards.

William Hogarth: Detail from The Tavern Scene (A Rake’s Progress), between 1732 and 1735. Oil on canvas. London: Sir John Sloane’s Museum.

The popularity of both woollen and silk stockings is indicated by the fact that, already at the end of the 15th century, there were thousands of professional knitters in Europe. Yet, despite their prominence in this period, there is no clear surviving documentation about how hand-knitted stockings were made or what they actually looked and felt like in real life. Restoring this lost historical material world by reconstruction can make invisible history visible and bring these items and the technology to life.

Reconstruction through citizen science

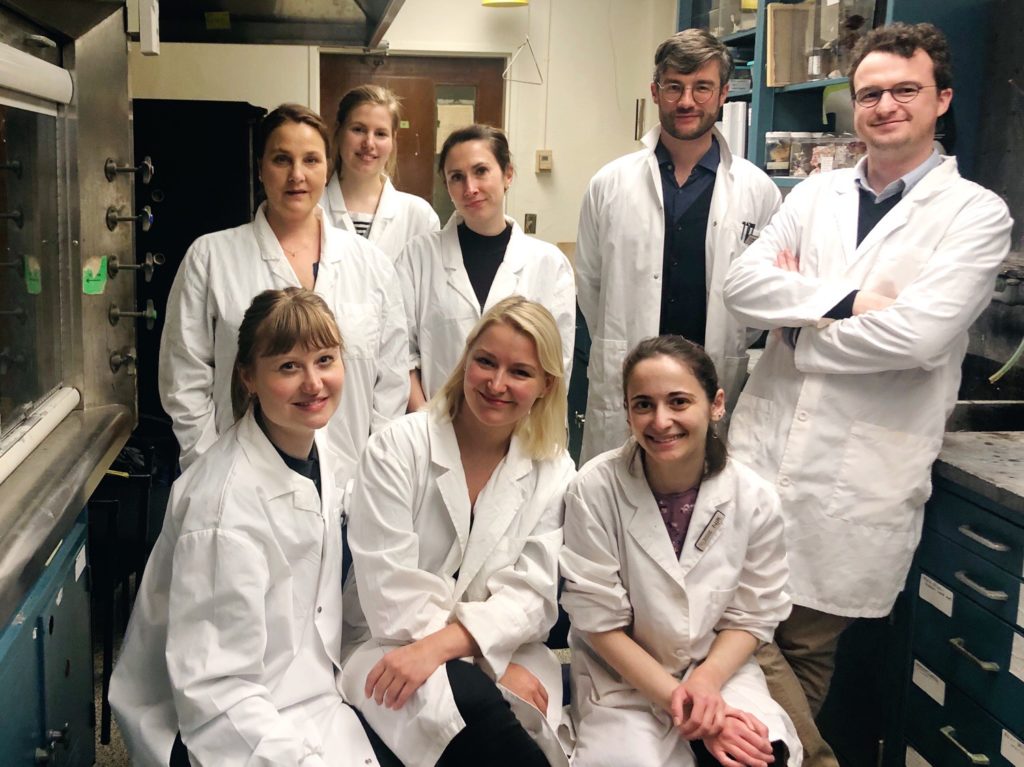

In 2019, our Refashioning project set up a citizen science project, in order to examine the process of stocking-making through historical reconstruction.

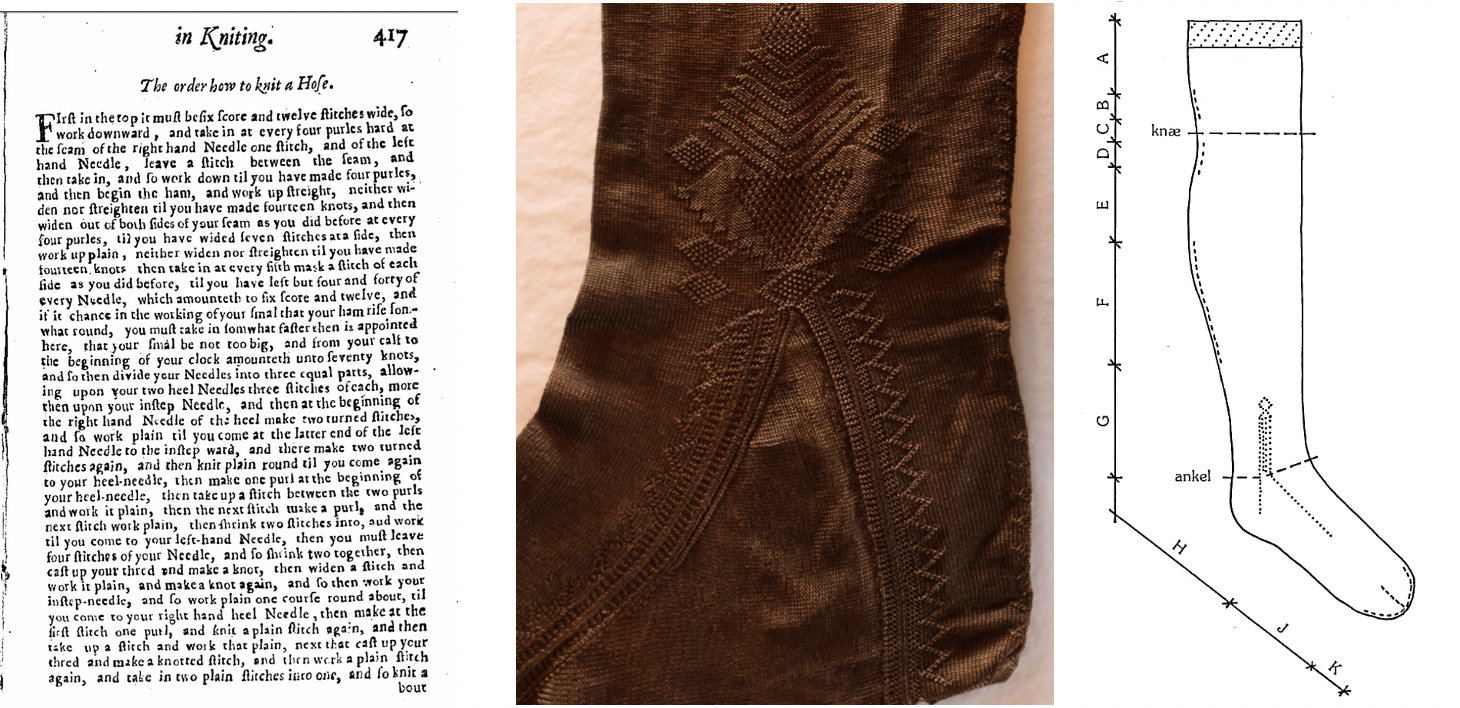

Towards this end, we recruited 35 voluntary knitters to carry out three different reconstruction projects. One of these was to remake a simple artisan stocking based on examples found in excavations in Copenhagen; another one to create a stocking based on an early modern English recipe titled “The order how to knit a Hose” (1655), and the third one to replicate an extant hand-knitted 17th-century silk stocking, today conserved at the Turku Cathedral Museum.

The most ambitious and complex of these projects was the reconstruction of the fine silk stocking, because making a fine silk stocking required a high level of skill. Together with the group of our knitters, we set ourselves to work out collectively how we could replicate the Turku stocking as accurately as possible. So how can one reconstruct a historical silk stocking?

Reconstructing a knitted silk stocking

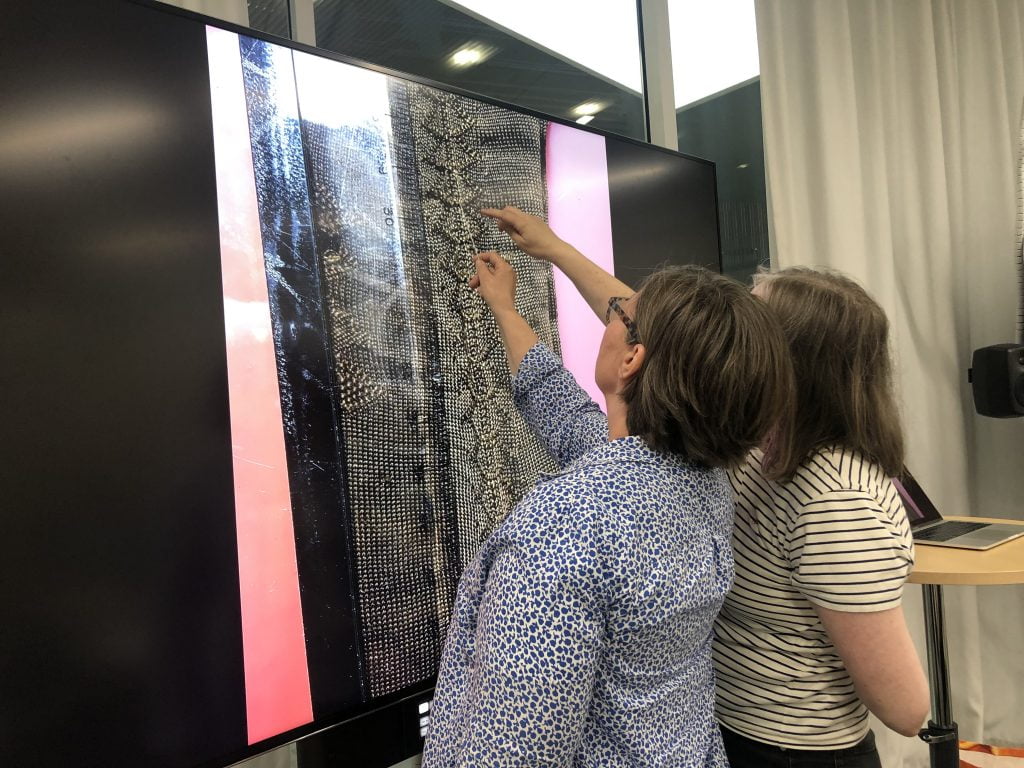

Our silk stocking reconstruction project started at the Turku Cathedral Museum where our team members first measured the stocking and took close up images of it. With the museum’s permission and the help of the conservator, we were also allowed to take a tiny fibre sample at the edge of the stocking so that we could do scientific testing. With these technical details, our knitters began to examine the structure of the stocking and work on the knitting pattern.

Our pattern group members counted every stitch of the original stockings to create the knitting instructions for the reconstruction.

After this initial stage of technical analysis, our team began investigating where we could find right kind of silk yarn. We carried out a fibre analysis at Aalto University nanomicrosocpic lab of the original sample that we had taken in Turku. The results showed that the stocking had been made of bombyx mori -a traditional silk that had been produced by mulberry silkworms.

We found a silk farm in Calabria, Italy, called Nido di Seta, that still produces hand-reeled bombyx mori silk, and we travelled there to investigate how this silk was actually made, and how many silk cocoons should be used at once to get the right thickness for our silk yarn. We were also able to order our silk yarn for the stockings from this farm.

At the same time, we also tried to figure out what colour the stocking had orginally been. We sent our fibre sample for our colleague at the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands and he made a dye and mordant analysis of the sample. The results showed that the stocking had been originally black according to the fashion of the time.

When all these preparations had been completed, our knitters could finally begin to try the silk and the knitting needles, and start knitting the stockings. We also asked them to take notes during the knitting process so that we would have some experiential documentation to analyse after the project.

Now that the project has been running for 1,5 years, we have already nine ready-made stockings. The only thing we still have to do to the stockings is the finishing processes and dyeing.

What have we learned from this project so far?

This project has shown that knitting a silk stocking was technologically challenging. It takes about 200 hours, or even longer, to knit just one silk stocking. This is because the yarn is very thin and the stocking is knitted using very fine 1mm knitting needles.

Secondly, we learned that getting optimal kind and quality of silk yarn was challenging at a time when silk was processed by hand from the beginning to the end. Our own silk yarn, for example, was not of the highest quality, because the summer was quite rainy and as a result part of the silk was glued together, as we can see in this picture.

Thirdly, we have learned that dyeing was a challenging process in the seventeenth century. Good intensive black in this period, when all colours were dyed using natural dyestuffs, was one of the most difficult colours to achieve. The dye experiments that were carried out in a Burgundian Blacks research workshop , organized in by the ERC funded ARTECHNE project and Claudy Jonstra in the Netherlands in 2019, for example, showed how a black that was initially beautiful had turned into brown overnight.

In the light of these material and technological challenges, it is not surprising that silk stockings were expensive luxury products and one of the most important innovations of fashion that high-ranking elites used to set themselves off from the rest of the crowd in sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Even though the laborious production process and the high cost made silk stockings rare among our artisans, our data shows that sometimes even lower ranking artisans and shopkeepers were able to wear silk stockings. For example, Giovanni Neri, a shopkeeper from the neighbourhood of Pantaneto in Siena, who died in 1588 in, owned a pair of white stockings ‘of silk and knitted’ that belonged to his wife[1].

Notes and further reading:

[1] Archivio di stato, Siena, Curia del Placito 263, 188, 76v.

Carlo Belfani, Calze e maglie. Moda e innovazione nell’industria italiana della maglieria dal Rinascimento a oggi (Mantua, 2005).

Andrea Caracausi, ‘Beaten Children and Women’s work in Early Modern Italy’, Past and Present, no. 222 (Feb 2014), pp. 95–128.

Jeremy Farrell, Socks & Stockings (London, 1992).