In 1587 and 1588 Alessandro Vignarchi, a peddler in the Tuscan countryside, was traveling across the mountainous area northeast of Florence. Alessandro was selling a wide array of products: grains, wine, cheese, but most importantly, woolen and linen cloth. He was part of a family of retail traders, that had been operating in the area since at least 1570, with their main activity based in San Godenzo.

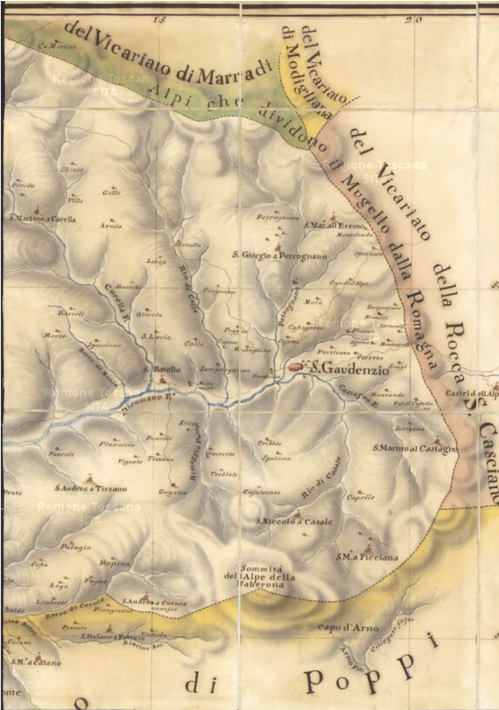

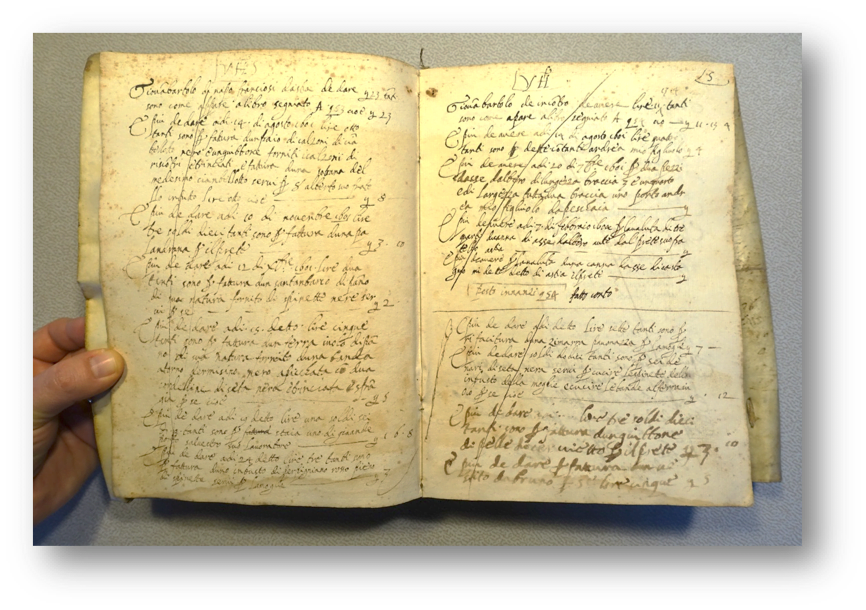

Figure 1. Morozzi Ferdinando, Vicariato di Pontassieve, 28 September 1780. Source: Cartografie Storiche Regionali, Regione Toscana.

Alessandro spent several years traveling throughout the different valleys, meeting people that not only came from the Tuscan Apennines , but also from the countryside of Lucca, from the nearby Emilia region, and from the Chianti area. With his activity he reached a few remote villages that still today are in the middle of the Apennine woods.

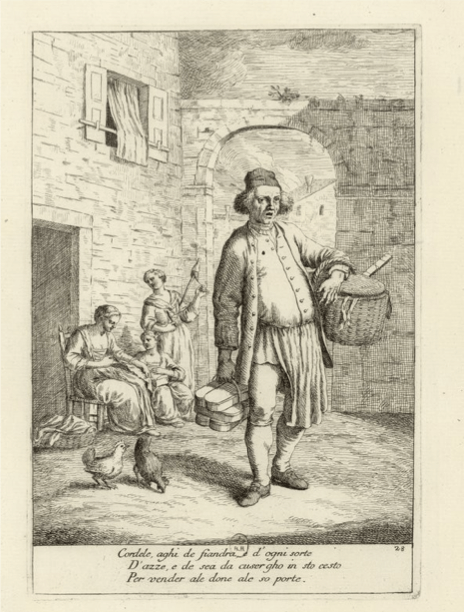

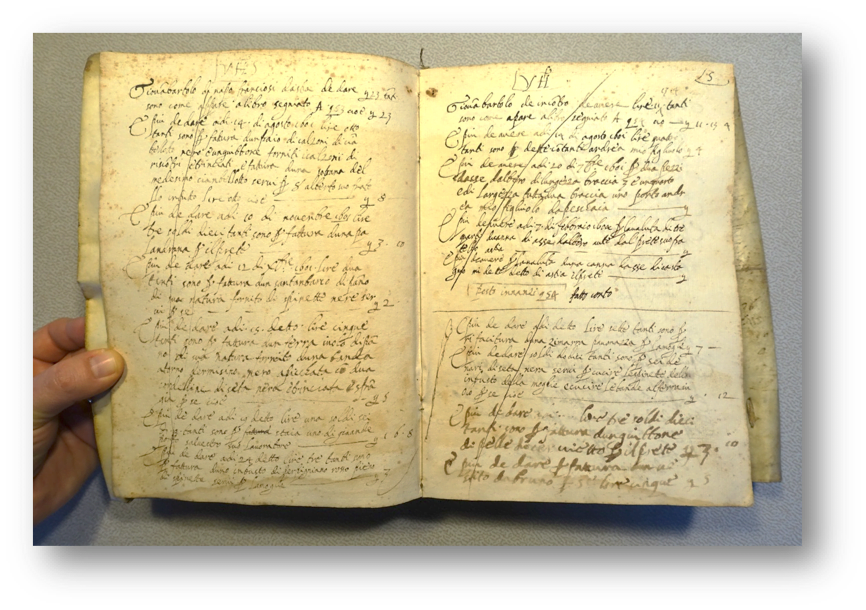

Alessandro’s activity, and that of his family, is testified by a series of account books that are organized using single entry bookkeeping, which chronologically report the debts and credits of the peddler, recording the transactions in the name of the creditors/debtors.

These books will be the basis of my new research, which will focus on consumption patterns, information networks, and fashion culture among non-urban populations in the early modern period. The Vignarchi case study, besides being an interesting family saga by itself, deals with several historiographical issues. Firstly, fashion historians have showed how trends and fashions spread horizontally and vertically across social groups. However, it remains unclear which information networks and carriers were diffusing trends and fashions among lower social groups. Secondly, the peddler’s activity is also connected to more recent historiographical debates in mobility and migration studies. Thanks to this peculiar source, it will be possible to address issues related to the identity of buyers, the role of peddlers in the spread of fashion, and the influence of the city on the countryside. It also helps us to understand the role of geographical networks on habits of consumption. Moreover, peddlers played an important role in the creation of informal social relations, thanks to their action in settling credits and debits among their clients.

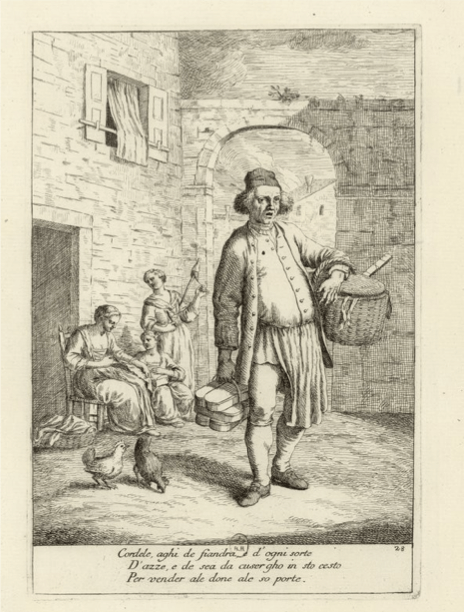

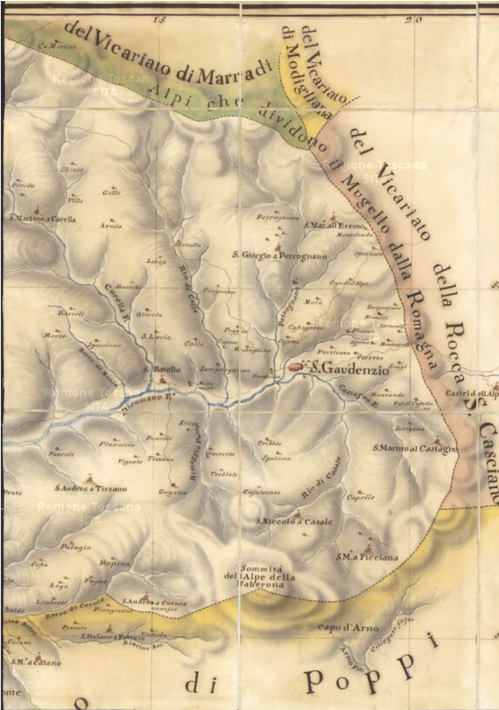

Figure 2. Gaetano Zompini, Le Arti che vanno per via nella città di Venezia (1746-1754).

The role and relevance of the itinerant trade has been well-studied, particularly for Northwestern Europe and Italy, mostly for the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Places such as the countryside and the mountains have been left behind in research, while a preference has been accorded to urban areas. While most European cities provide rich documentation of their retail systems during the ancién regime, the countryside and mountainous areas suffer from a lack of research, in particular for the early modern period. This is due to a lack of sources for several of these regions, but also the historiographical idea that the landscape of consumption in these territories was significantly less developed with respect to consumer culture.

However, understanding peripheral areas is as important as understanding the consumption patterns and retail trade of cities like Florence or Venice, since in this period the biggest share of the population lived in non-urban areas. And, at least in Italy, this demographic distribution did not change until the second half of the nineteenth century, when the country started to industrialize.

Peddlers and itinerant traders are figures that are always difficult to define precisely. It is difficult to find, including for urban areas, sources that may shed light on their roles, functions, and movements since they very often moved along the borders of the different economic systems that characterized the Italian regions. Despite the difficulties in following their exact activities and displacements, these traders had a fundamental importance as suppliers to non-urban areas, for the exchange of small goods and textiles, the circulation of news, and for the connections they created between areas. Interesting, for instance, is the role of itinerant traders in the labor market and work mobility described in the work of Laurence Fontaine.

The development of this professional figure was probably a result of a context characterized by people moving seasonally from one place to another, and in a situation characterized by rural pluri-activity (that was linked to the issue of subsistence in several areas of the peninsula). A gradual process caused some of the rural workers to transform into itinerant traders.

Itinerant traders were, of course, involved on a more general level in regional and supra-regional trade, since they had strong ties with city merchants, the main suppliers for their goods. Peddlers not only sold their products to peasants in the most remote valleys of the Apennines, but also attended fairs and weekly markets that were held at the foot of the mountains, and directly supplied from the city’s merchants. In the case of Alessandro, because of his strong ties with Francesco Vignarchi, a cousin who was already a retailer of cloth, we can assume he infrequently needed to travel down to Florence to buy the merchandise himself.

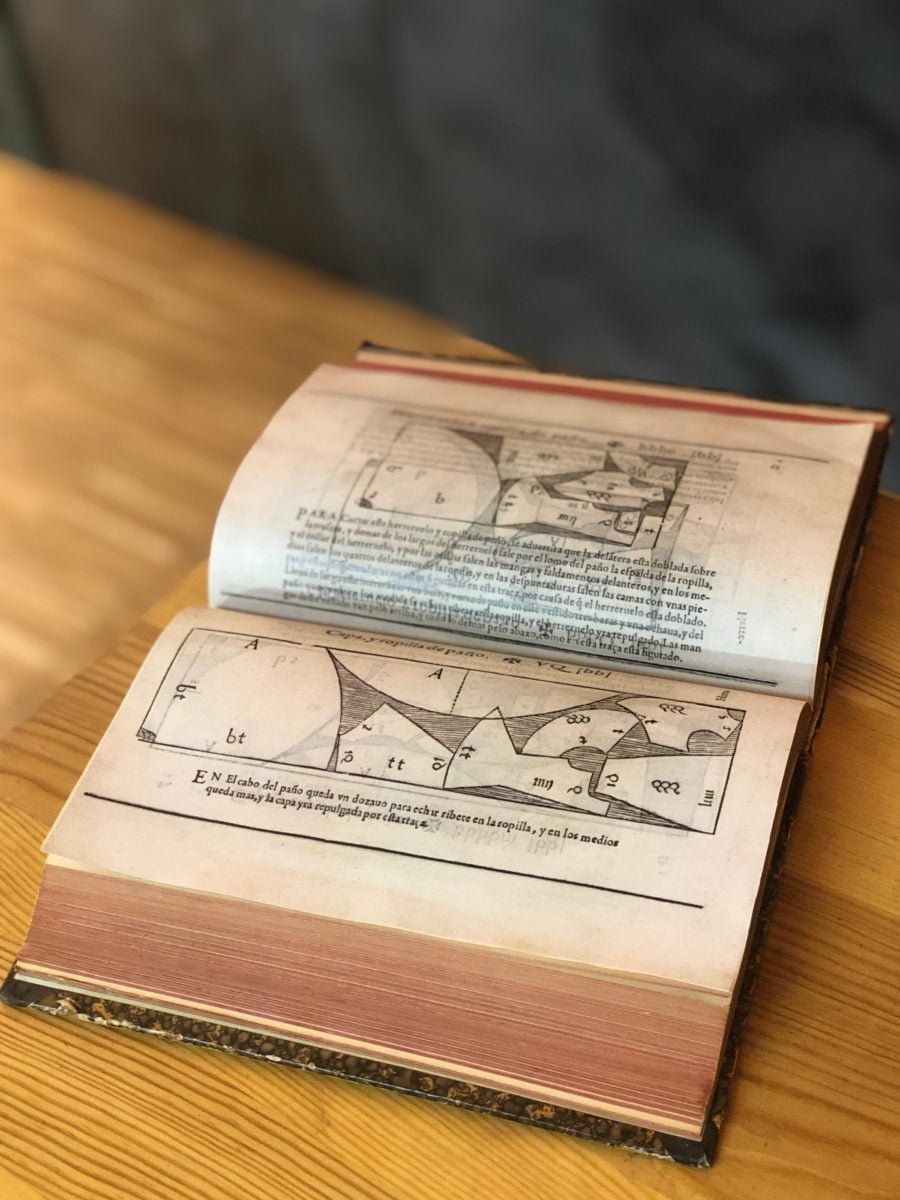

Figure 3. Picture of a carta from the Vignarchi account book.

Peddlers, in the context of the Apennine area, had a strategic role since they connected different valleys and villages, spreading news (of different sorts) and products (particularly locally manufactured goods, as in Alessandro’s case pannibigi casentini– an heavy wool cloth from Stia – and wheat, which was insufficiently produced in the mountain area). In this sense, itinerant traders had a fundamental role in supplying the valleys with these vital goods. And, hopefully this research, now in its initial stage, will shed light on the activity of Alessandro Vignarchi and his family and help us understand what was happening in the mountains surrounding Florence, one of the most fashionable cities of the early modern age.

Finally, this research may show that peddlers were responding to the demand for flashy items by inhabitants of the Apennines. It is unlikely that these rural people did not have any sense of fashion, since, as a trimming master in mid-eighteenth-century Turin said: “Ama il contadino la comparsa, ma le facoltà non s’adattano al di lui desiderio”.[1]

[1]The peasant loves to appear, but his wealth doesn’t match his desire.