Director’s greetings: What have we been up to?

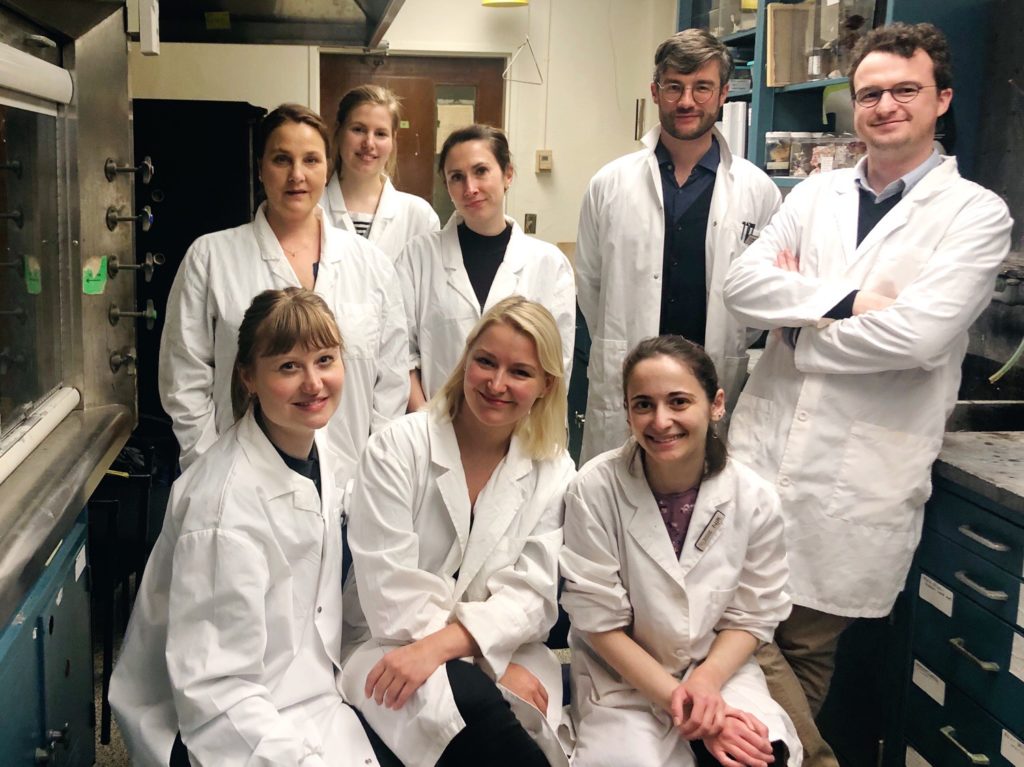

In June 2019, out team gathered in Copenhagen for our second ‘milestone’ meeting, where we reviewed our past results and made both short-term and long-term goals. This meeting represented a moment of great joy and pride. Our team members have been working extremely hard, and I could all really see how much we have achieved during the past 1,5 years.

So what have we been up to?

During the first year of our research in 2018, we all focused on identifying and gathering data. This phase is now complete and we have achieved two very important milestones. The first one of these is that the archival research, headed by our research fellow Stefania Montemezzo and produced in collaboration with our PhD student Anne-Kristine Sinvald Larsen, myself, and our research assistants Mattia Viale and Umberto Signori, is now complete and the data is ready to be uploaded on our brand new database. This database, created in collaboration with Jodie Cox from Wildside, will include clothing and textile items that belonged to ordinary families in the early modern period, and it will be the biggest early modern textile and clothing database created so far. It includes altogether nearly 30.000 items from Italy (Siena, Florence, Venice) and a further several thousand items from Denmark (Helsingør). This data will provide and important basis for our analysis, both in terms of our publications as well as our hands-on experiments, and the database will be eventually available online for anyone to use.

Refashioning the Renaissance database. Image copyright Refashioning the Renaissance Project.

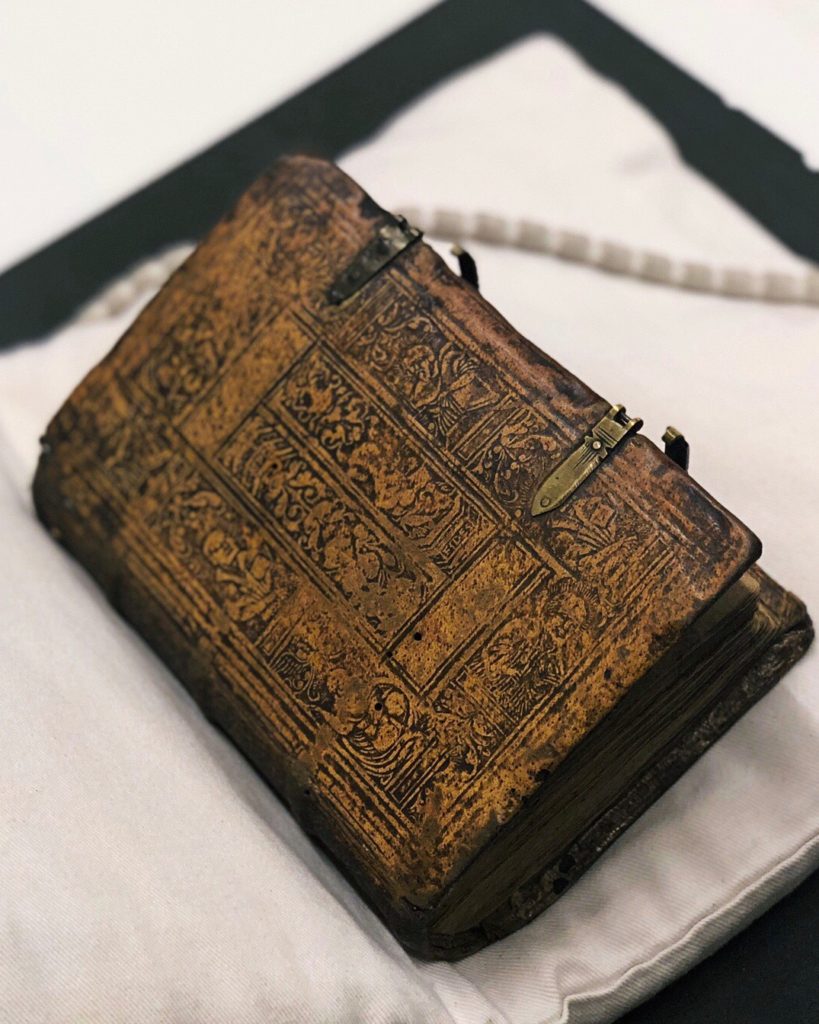

The second important milestone is that our data on printed sources, headed by our postdoc researcher Michele Robinson, is also complete. Michele has been focusing especially on collecting cheap printed recipes that were intended for consumers at the lower end of social scale, and especially those that have to do with the care of textiles and clothing in the domestic context, such as mending, cleaning and dyeing at home. This data provides an important foundation for some of our experiments where we explore and evaluate the meaning of both the recipes and some of the domestic textile practices that might have been available for our artisans and shopkeepers.

Book of Secret in the Wellcome Collection. Photo copyright Refashioning the Renaissance Project.

Dirty Laundry workshop, where we tested recipes from the printed sources Michele Robinson has collected. Photo copyright Refashioning the Renaissance Project.

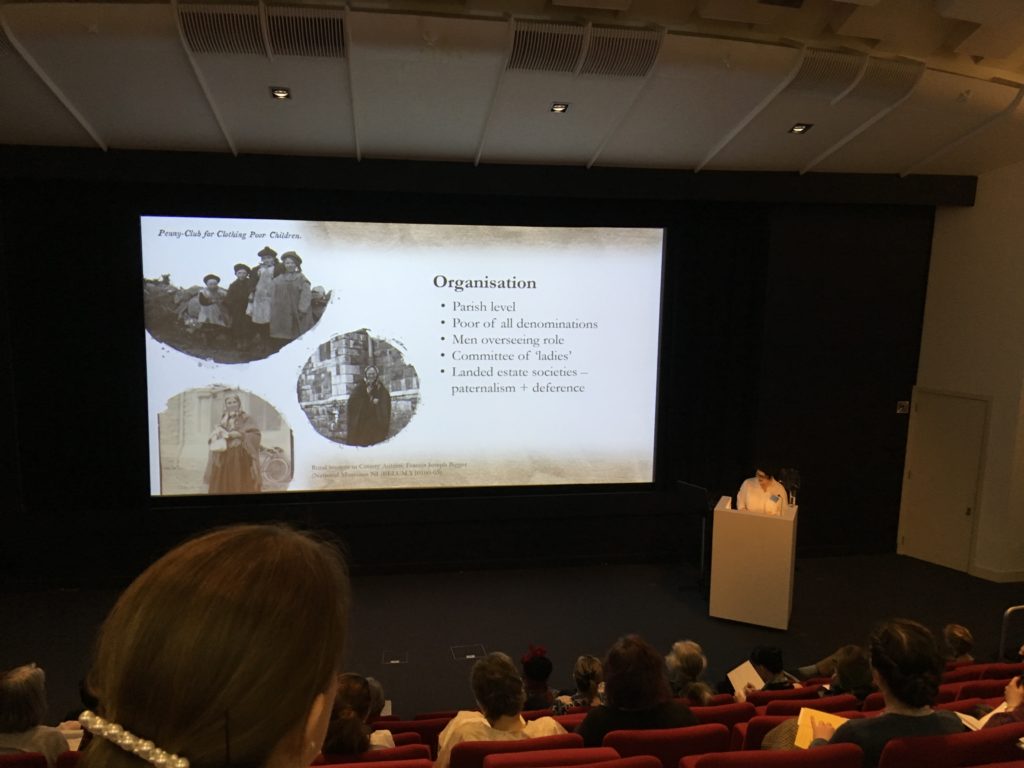

During our second year, in 2019, we have moved on from exclusive focus on data to explore and analyse how various experiments, reconstruction and engagement with materials and textile objects can help us to better understand and access past practices. We have organized workshops on domestic dyeing and tailoring, and we have two further workshops on colour and imitation coming up. We have also been running our citizen science project where we experiment with early modern knitting, and we are growing dye plants in our green house. In addition, we have participated in several courses where we have learned about how historical recipes could be used in textile dyeing; how silk-, linen- and woolen-fibres were prepared in the early modern period; how tailors worked, and how both precious and more ordinary fabrics and trims were woven in the early modern period.

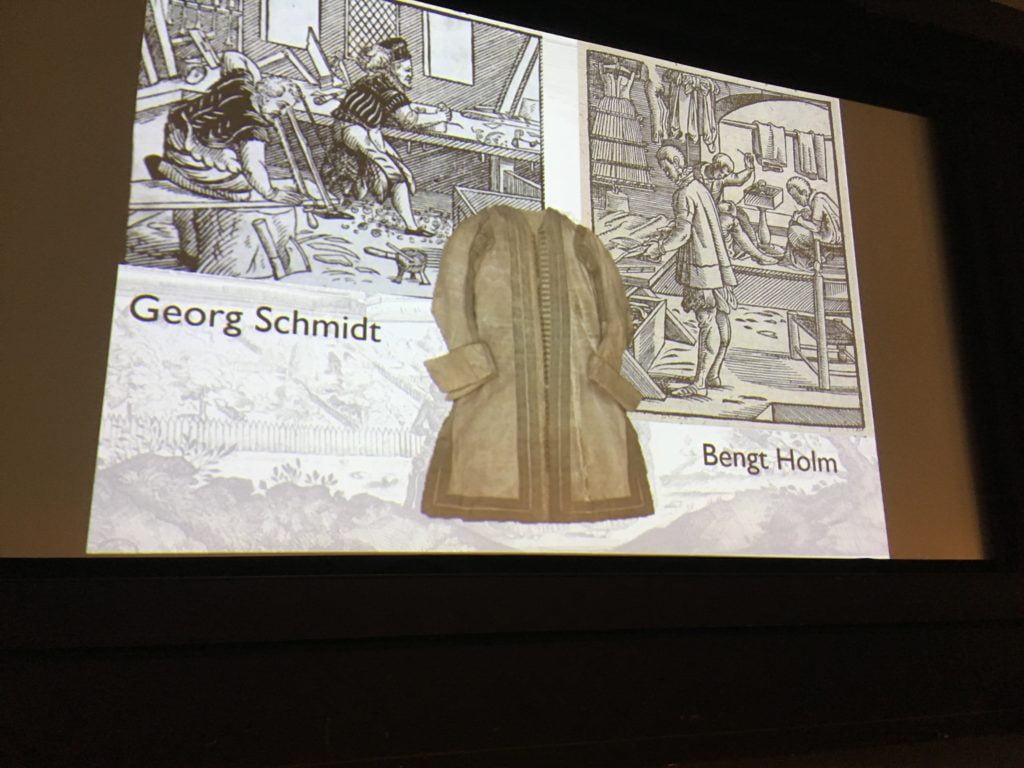

One of our exciting projects is the reconstruction of an artisan’s doublet, headed by our second postdoc Sophie Pitman and created in collaboration with Jenny Tiramani and the School of Historical Dress. This experimental project allows us to explore all stages of doublet production, such as creating finished fibre from raw material, weaving, dyeing , and making and wearing the garment. We are also working with an animator Maarit Kalmakurki to produce a 3D reconstruction of our doublet. This research will eventually form one of the most important ways for us to analyse how digital and material reconstruction can be used as a method in cultural studies of dress.

Fibre Analysis of the 17th century stockings from Turku Cathedral. Photo copyright Refashioning the Renaissance Project.

Stain removal test at the Dirty Laundry workshop. Photo copyright Refashioning the Renaissance Project.

Sophie Pitman reeling silk in Calabria. Photo copyright Refashioning the Renaissance Project.

Refashioning team learning to spin in Trelleborgen Viking Museum. Photo copyright Refashioning the Renaissance Project.

The results of our project will be presented in our final conference and exhibition at Aalto University, Helsinki, on 11-13 September 2020. More information will follow soon, but do not forget to reserve those dates in your calendar!