Did ordinary Italians have a ‘Renaissance’? Discover how artisans lived and connected with culture from my new book!

Italian Renaissance is known mainly through art works, decorative objects, and fashion manufactures that were owned, used and admired by the high-ranking wealthy elites. Before we started the Refashioning the Renaissance project, few scholars had been interested in studying how the lower classes experienced the Renaissance culture. So how did ordinary Italians, such as shoemakers, barbers and bakers and their families, connect to the Italian Renaissance culture through their artefacts, cultural practice and appearance?

We can admire the richness of Renaissance material culture in many surviving Renaissance images, such as in the early sixteenth-century image of an orderly and affluent household by Vittore Carpaccio on the left. A painting by Vincenzo Campi, created in 1580, on the right, however, provides a rare visual window to the material world within reach of modest peasant or working families. Depicting a moment on 11 November, after the end of the harvest, when many families in the countryside traditionally moved house, the painting shows chests, metal buckets, and other household wares piled up on the back of a donkey. Open to public view, such possessions revealed much about a family and how it wished to present itself.

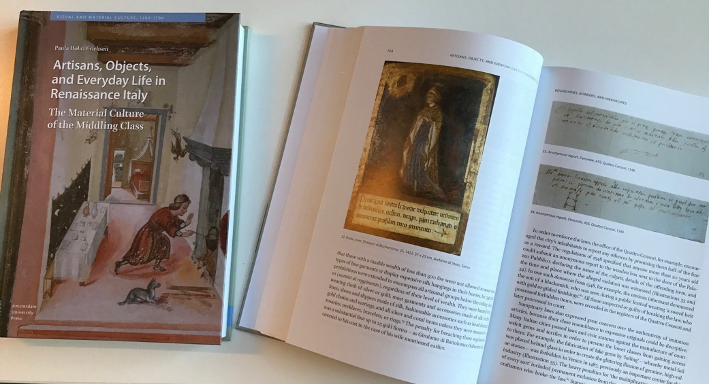

My new book Artisans, Objects and Everyday Life in Renaissance Italy: The Material Culture of the Middling Class, published recently by Amsterdam University Press, explores—for the first time in depth—the question of, could people lower down the social scale participate in the markets for luxury goods and novelties and engage in Renaissance culture?

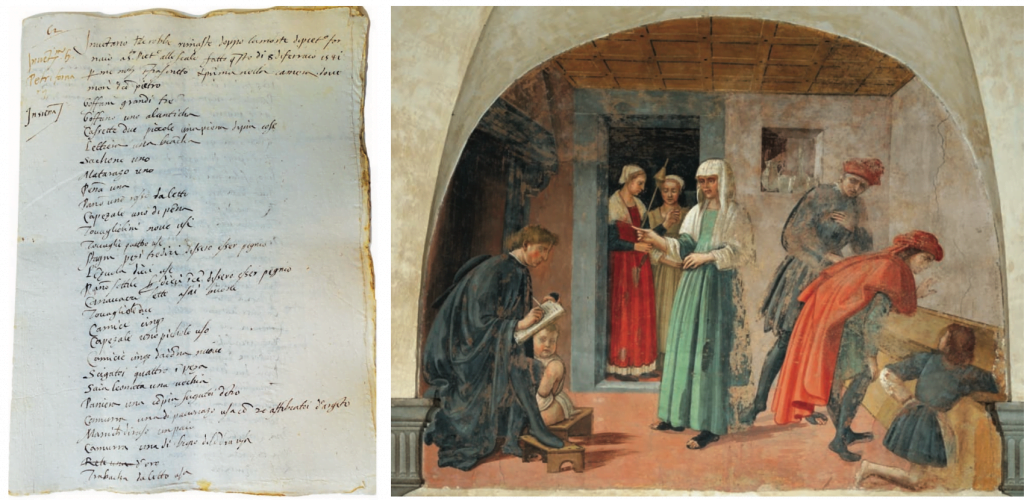

Post-mortem inventories are an important archival source for material culture and fashion historians to investigate what kind of material artefacts people owned. Here, on the left, we can see an inventory of the sixteenth-century baker Pietro, listing all the belongings he had owned at the moment of his death, and, on the right, a fifteenth-century Florentine fresco painting showing the process of taking a household inventory.

Using a rich blend of archival evidence from sixteenth-century Siena, such as post-mortem inventories illustrated above, it explores how local artisans and tradesmen and their families conducted their lives in Italy in the first half of the sixteenth century; how they acquired a wide range of artefacts, furnished their homes, and managed their domestic economies and consumption; what types of luxury items and small personal belongings were exchanged and circulated in dowries at artisan levels; and how families of artisan rank socialized in their homes and celebrated their weddings.

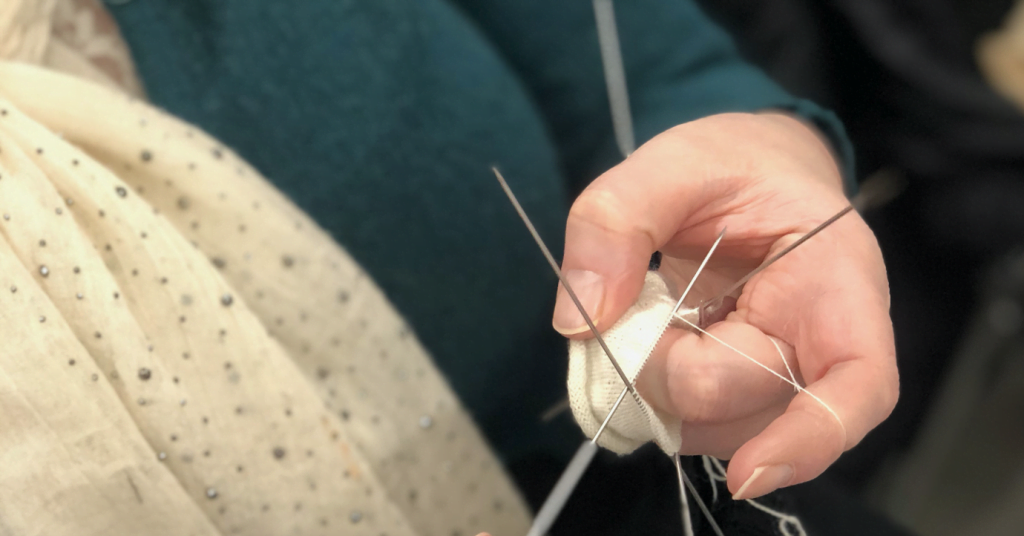

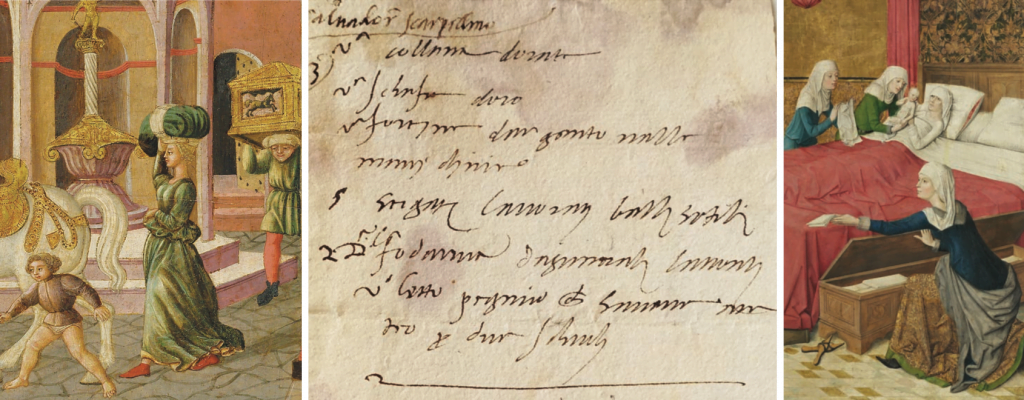

Marriages and wedding celebrations were important occasions when luxuries were acquired and circulated. The bride’s dowry, transported to the new home in a wedding chest, included a number of luxuries even at the lower social levels, such as fine linens, gold embroidered scarves and snoods, jewellery and furniture. Even the modest stone-cutter Salvatore’s wife’s dowry, as appears in the document above, included such treasured valuables. Fine white, decorated household linens were an sign of the family’s status and an important store of household wealth. Chests of linen were often placed on display after the ceremonial dowry procession.

As one of the greatest challenges of studying non-elite groups is the difficulty of providing and defining appropriate categories so that it is clear what terms such as ‘artisan’, ‘small shopkeeper’ or ‘middling class’ denote, this book does not only offer new knowledge about social and cultural practice at the lower levels of society, but it also provides an important foundation for our Refashioning the Renaissance project to define what we mean when we study the lower social groups and their clothing, fashion and appearance.

Ordinary artisans, such as shoemakers, innkeepers and tailors, usually enjoyed a modest position in society. Some artisan groups, however, such as skilled master tailors, tried to claim new status and worth in the sixteenth century through greater involvement with the intellectual properties of their work, or their association with ‘design’.

By focusing in my book on the material culture and lives of men of different economic and professional statuses among the artisan ranks, some of whom were immigrants and poor, others modestly prosperous and powerful, and learning what their particular economic and material conditions were, who they connected with, what they owned, and what kind of lifestyles they led, I hope that this monograph allows the reader to understand the diversity and richness of artisans’ and shopkeepers’ cultural experience in sixteenth-century urban Italy, and makes visible the artisans’ individual experiences – their hopes and happiness, industry and inefficiency, fortunes and failures.

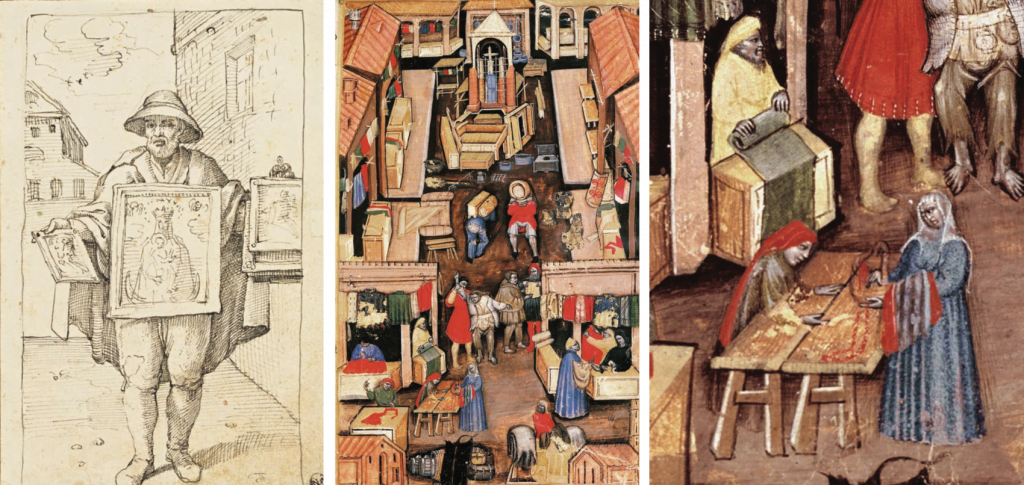

Many kinds of art and decorative works, textiles, clothing items and household wares were available ready-made, both new and used and in varying prices, for a range of consumers through street-sellers, local shopkeepers and auctions. Here, a sixteenth century peddler is selling cheap prints, while a number of household articles are available at the 15th-century Bolognese marketplace. Many families had to pawn some of their personal belongings, in order to borrow money for their purchases. Pawnbrokers had a common presence in the local marketplaces, as appears from the detail of the marketplace image.

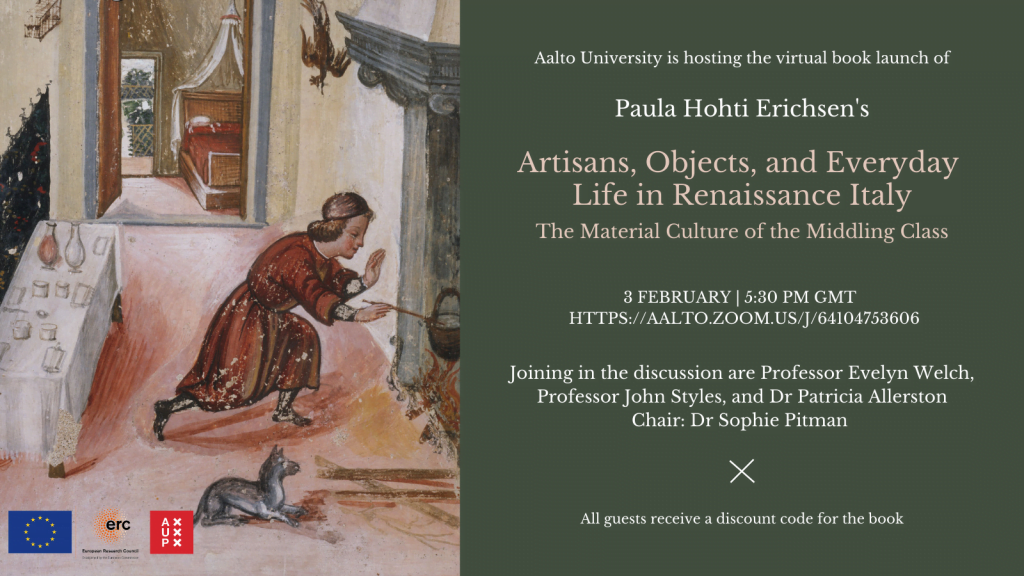

Book launch

Please join me and Prof Evelyn Welch, Prof John Styles and Dr Patricia Allerston for a launch of my book “Artisans, Objects and Everyday Life in Renaissance Italy: The Material Culture of the Middling Class”, hosted by Aalto University. The event will take place on Zoom on Wednesday, 3 February 2021 at 17:30 GMT at:

https://aalto.zoom.us/j/64104753606

I would have very much liked to offer you a glass of sparkling wine and celebrate the event with a toast, but, since this is not possible now, you are welcome to bring along a glass of wine, a cup of tea or anything else, if you like.

There will be a 50% discount code available for anyone wishing to buy the book.

Images

Image 2: Vittore Carpaccio, Birth of Mary, ca. 1502–1504. Oil on canvas, 129 x 128 cm. Accademia Carrara, Bergamo.

Image 3: Vincenzo Campi, St. Martin’s Day, also known as Trasloco (‘Moving Home’), post 1572. Painting, 227 x 163 cm. Museo Civico Ala Ponzone, Cremona.

Image 4: Inventory of the Pietro, a baker in San Pietro alle Scale, 1542. Archivio di stato di Siena, Curia del Placito 706, no. 62, 8 February, 1541/42.

Image 5: Workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio, Inventory of a Legacy of the Magistrates, late 15th century. Fresco.Florence, San Martino dei Buononimi.

Image 6: Giovanni di Ser Giovanni (Lo Scheggia), The Story of Trajan and the Widow (detail). Cassone panel, tempera & gold on panel, ca.1450. Private Collection.

Image 7: Listing of dowry items belonging to the wife of Salvatore sculptor, CDP 677, 13, 1, 1528.

Image 8: Master of the Life of the Virgin, The Birth of Mary (detail), 1470–1480. Oil on panel. Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

Image 9: Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Allegory of Good Government (detail of a shoe shop), ca. 1337–40. Fresco, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena.

Image 10: Lorenzo Lotto, Scenes from the Life of Saint Barbara (detail), ca. 1523–24. Fresco. Trescore Balneario, Suardi Chapel.

Image 11: Giovanni Battista Moroni, The Tailor, 1565–70. Oil on canvas, 100 x 77 cm. The National Gallery, London.

Image 12: Anonymous, Print Seller after Annibale Carracci, 17th century. Etching, 28 × 19 cm. Musée du Louvre, D.A.G., Paris.

Image 13 & 14: Manuscript illumination from Matricola della società dei drappieri, 1411. Museo Civico Medievale, Bologna.